Imagine standing on a rocky outcrop high in the Canadian Rockies, the wind whipping through your hair as you scan the limestone cliffs around you. What you’re looking at isn’t just beautiful mountain scenery – it’s actually a massive graveyard that’s been waiting millions of years to tell its story. These towering peaks and valleys hold some of the most incredible fossil discoveries on Earth, preserving ancient creatures that lived when this entire region was covered by warm, tropical seas. The Canadian Rockies aren’t just a modern natural wonder; they’re a time machine that takes us back hundreds of millions of years to when life on our planet looked completely different.

When Mountains Were Ocean Floors

The story of fossils in the Canadian Rockies begins with a mind-bending fact that most people find hard to believe. These massive mountain ranges, some reaching over 12,000 feet into the sky, were once the bottom of ancient oceans. Around 500 million years ago, western Canada was submerged under vast tropical seas that teemed with bizarre and wonderful creatures. As these ancient animals died, their remains settled into the muddy ocean floor, layer upon layer, creating what would eventually become the fossil-rich limestone and shale formations we see today. When massive geological forces later pushed these ocean floors skyward to form the Rocky Mountains, they brought with them an incredible treasure trove of prehistoric life.

The Burgess Shale: Earth’s Most Famous Fossil Site

Hidden high in the Canadian Rockies lies what many scientists consider the most important fossil site on our planet – the Burgess Shale. Discovered in 1909 by paleontologist Charles Walcott, this remarkable location preserves soft-bodied creatures from 508 million years ago with such incredible detail that you can see their guts, gills, and even their last meals. Unlike most fossil sites that only preserve hard parts like shells and bones, the Burgess Shale captured entire ecosystems in stunning detail, showing us what life looked like during the Cambrian explosion when complex life forms first appeared on Earth. The fossils here are so well-preserved that scientists can study the internal organs of creatures that died half a billion years ago, giving us an unprecedented window into ancient life.

Anomalocaris: The Cambrian Sea Monster

One of the most spectacular discoveries from the Burgess Shale is Anomalocaris, a creature so bizarre that early paleontologists couldn’t figure out what it was. This ancient predator grew up to six feet long, making it a giant by Cambrian standards, and ruled the prehistoric seas with massive front appendages that it used to grab prey. Its name literally means “abnormal shrimp,” but this creature was nothing like any animal alive today – imagine a massive swimming shrimp with huge grasping arms and circular jaws lined with sharp teeth. Anomalocaris was the apex predator of its time, hunting trilobites and other early animals in the warm Cambrian seas that covered what is now the Canadian Rockies. Finding complete specimens of this ancient monster has helped scientists understand how early predators evolved and shaped the development of life on Earth.

Trilobites: The Survivors of Ancient Seas

Few fossil creatures capture the imagination quite like trilobites, and the Canadian Rockies have yielded some of the most spectacular examples ever found. These armored marine arthropods dominated Earth’s oceans for nearly 300 million years, making them one of the most successful groups of animals in our planet’s history. In the Rocky Mountain fossil beds, paleontologists have discovered trilobites with compound eyes containing hundreds of individual lenses, allowing these ancient creatures to see predators and prey with remarkable clarity. Some species found in the region had bizarre spines and horns that made them look like underwater porcupines, while others developed the ability to roll into tight balls when threatened, just like modern pill bugs. The diversity of trilobites preserved in Canadian rock formations tells an incredible story of evolution and adaptation over millions of years.

Ancient Coral Reefs in the Mountains

Walking through certain areas of the Canadian Rockies today, you might stumble across what looks like strange, circular patterns in the rock – but you’re actually looking at the remains of massive coral reefs that once thrived in tropical seas. These ancient reefs, some dating back over 350 million years, were built by corals, sponges, and other marine organisms that created underwater cities teeming with life. The preserved reef structures in places like Jasper and Banff National Parks show us that this region once had a climate similar to modern-day Caribbean islands, with warm, clear waters perfect for coral growth. Scientists study these fossil reefs to understand how ancient marine ecosystems functioned and how they responded to changes in sea level and climate. The fact that we can walk among these ancient reefs on dry land today shows the incredible power of geological forces that lifted the ocean floor thousands of feet into the air.

Brachiopods: Ancient Filter Feeders

Among the most common fossils found throughout the Canadian Rockies are brachiopods, small marine animals that might look like clams to the untrained eye but are actually quite different. These creatures attached themselves to the seafloor with fleshy stalks and filtered food particles from the water using specialized feeding structures called lophophores. During the Paleozoic Era, brachiopods were incredibly diverse and abundant, with some species developing intricate shell patterns and others growing unusual spines and ridges for protection. In the Rocky Mountain fossil beds, paleontologists have found brachiopods preserved in their original living positions, still attached to ancient seafloor surfaces that are now exposed on mountain peaks. These fossils help scientists understand how ancient marine communities were structured and how different species interacted with each other in prehistoric ecosystems.

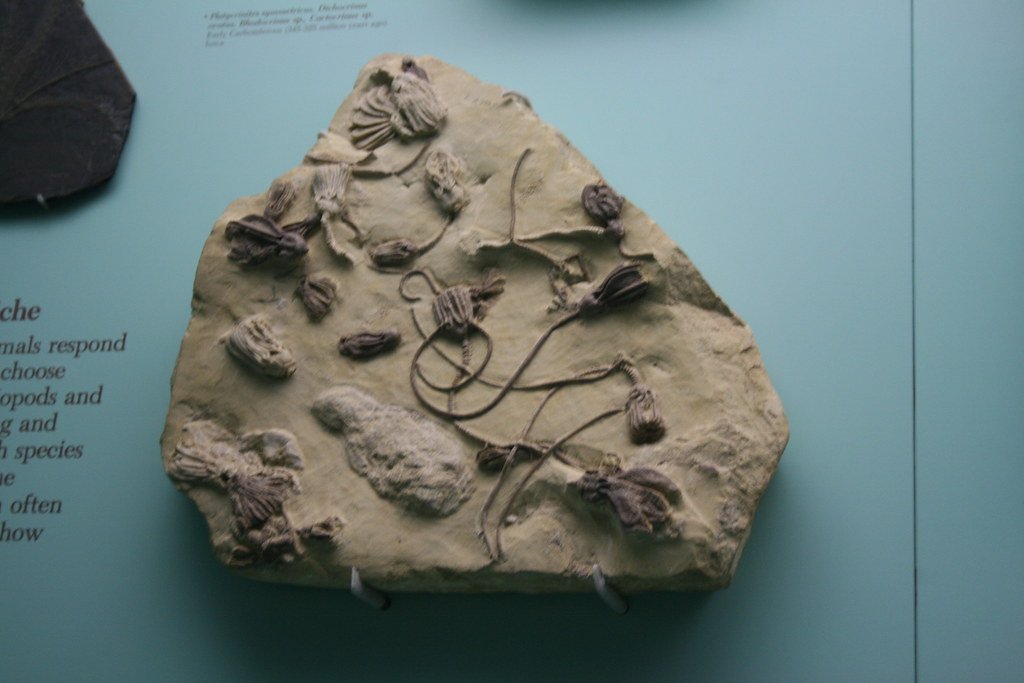

Crinoids: Sea Lilies of the Past

Some of the most beautiful and abundant fossils in the Canadian Rockies come from creatures called crinoids, which despite their plant-like appearance were actually animals related to starfish and sea urchins. These “sea lilies” formed vast underwater gardens on the floors of ancient seas, their flower-like heads swaying in the currents as they filtered microscopic food from the water. Crinoid fossils are so common in certain rock layers of the Rockies that entire cliff faces are made up almost entirely of their segmented stems, creating natural mosaics of circular patterns that look like ancient coins scattered through the stone. When these creatures died, their bodies often broke apart into thousands of small disc-shaped segments, which accumulated in massive beds that paleontologists call “crinoid gardens.” Finding a complete, intact crinoid fossil is rare and exciting, as it gives us a glimpse of these graceful creatures as they appeared in life, swaying gently in the warm Cambrian seas.

Stromatolites: Earth’s Earliest Ecosystems

Long before complex animals evolved, the ancient seas that covered the Canadian Rockies region were dominated by some of Earth’s simplest yet most important life forms. Stromatolites, which are layered structures built by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae), represent some of the earliest evidence of life on our planet and can be found in various locations throughout the Rockies. These ancient microbial mats grew slowly over thousands of years, trapping sediment and minerals to create distinctive layered rock formations that look like giant stone cabbages. The stromatolites found in the Canadian Rockies are particularly significant because they show us what Earth’s early atmosphere and oceans were like billions of years ago, when oxygen levels were much lower and life existed only in the seas. By studying these ancient structures, scientists can understand how early life forms began the process of adding oxygen to our atmosphere, making it possible for complex life to eventually evolve.

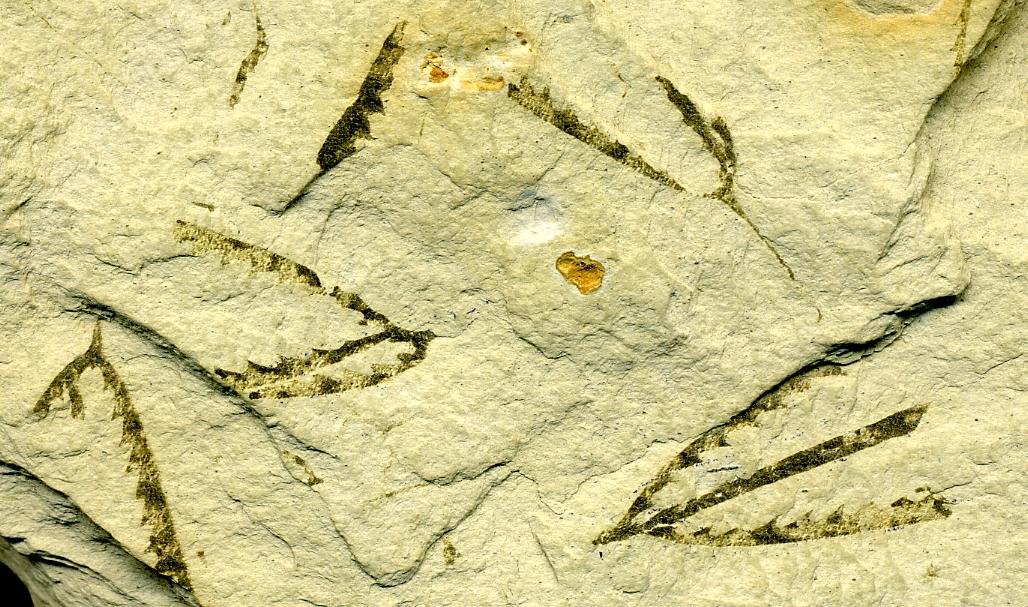

Graptolites: Floating Cities of the Ancient Seas

Among the more unusual fossils found in the shale formations of the Canadian Rockies are graptolites, extinct colonial animals that lived in interconnected tubes and drifted through ancient oceans like floating apartment complexes. These creatures, related to modern vertebrates, built intricate branching structures that housed dozens or even hundreds of individual animals, each one filtering food from the water through tiny tentacles. Graptolite fossils look like delicate fern fronds or saw blades pressed into the rock, and their rapid evolution makes them incredibly useful for dating rock layers and understanding ancient ocean conditions. In the Canadian Rockies, paleontologists have discovered graptolite species that lived for only short periods of geological time, making them perfect “index fossils” for determining the age of rock formations. The fact that these delicate creatures were preserved at all is remarkable, as their soft bodies and fragile colonial structures rarely survive the fossilization process.

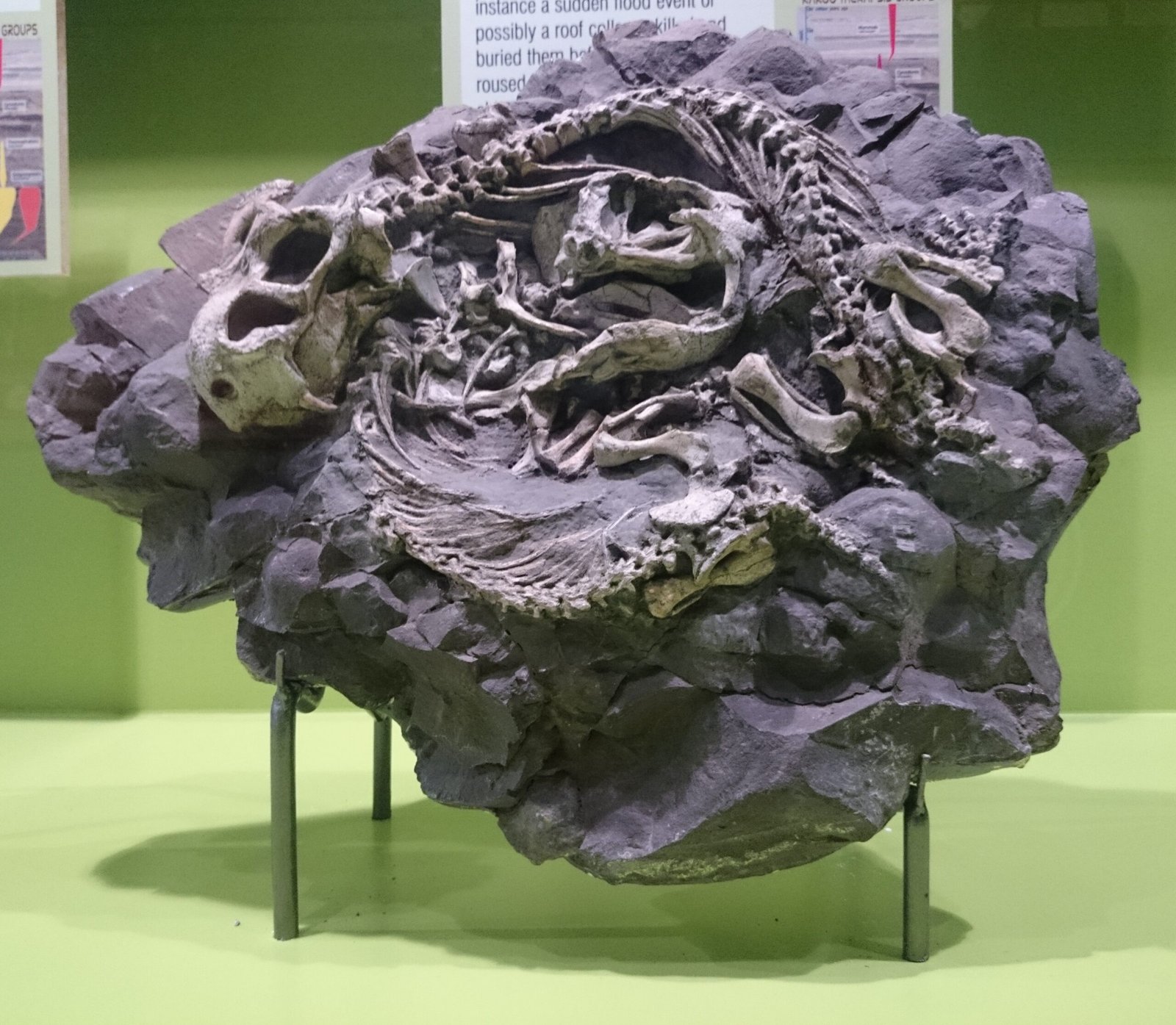

Dinosaur Tracks in Unexpected Places

While the Canadian Rockies are primarily known for marine fossils from ancient seas, some locations have yielded surprising evidence of dinosaurs that once walked across this landscape when it was dry land. In certain areas, paleontologists have discovered dinosaur trackways preserved in what were once mudflats and riverbanks during the Mesozoic Era, around 100 million years ago. These tracks tell stories of massive plant-eating sauropods trudging through swampy lowlands, swift-running theropods hunting along ancient shorelines, and herds of duck-billed dinosaurs gathering at prehistoric watering holes. The preservation of these tracks required very specific conditions – the sediment had to be just the right consistency to hold the footprint shape, and it had to be quickly buried before erosion could destroy the evidence. Finding dinosaur tracks in the Rockies reminds us that this region has experienced many dramatic changes over geological time, transforming from ocean floor to tropical lowland to the high mountain environment we see today.

Fish Fossils: Swimming Through Time

The limestone and shale formations of the Canadian Rockies have preserved some remarkable examples of ancient fish, giving us glimpses of how vertebrate life evolved in prehistoric seas. These fossils range from primitive jawless fish that looked more like swimming eels to early sharks with bizarre spiral-shaped teeth designed for crushing shellfish. One of the most exciting discoveries has been complete fish skeletons preserved with such detail that paleontologists can study their internal anatomy, muscle attachments, and even stomach contents to understand what these ancient creatures ate. Some of the fish fossils found in the Rockies represent evolutionary experiments that didn’t survive – creatures with unusual body plans and feeding strategies that died out millions of years ago. By studying these ancient fish, scientists can trace the evolutionary path that led from simple marine vertebrates to the complex fish we see in today’s oceans, and eventually to the first vertebrates that crawled onto land.

Ammonites: Coiled Shells of the Deep

Though not as abundant as in some other fossil-rich regions, the Canadian Rockies have yielded spectacular ammonite fossils that showcase these extinct marine predators in all their coiled glory. Ammonites were cephalopods related to modern squid and octopus, but they lived inside beautiful spiral shells that could grow as large as truck tires in some species. The ammonites found in Rocky Mountain formations show incredible diversity in shell shape and ornamentation, from smooth, streamlined forms built for fast swimming to heavily ribbed and spined varieties that may have lived in shallow reef environments. These fossils are particularly valuable because ammonite species evolved rapidly and had short lifespans, making them excellent tools for dating rock layers and correlating formations across different regions. When paleontologists find an ammonite fossil, they can often determine the exact geological age of the surrounding rock with remarkable precision, helping to piece together the timeline of life in ancient seas.

Bryozoans: Tiny Architects of Ancient Reefs

Among the smaller but no less fascinating fossils found throughout the Canadian Rockies are bryozoans, microscopic colonial animals that built intricate structures resembling lace, fans, or branching trees. These tiny creatures worked together to construct some of the most beautiful and complex fossil forms found in the region, with each individual animal living in its own small chamber within the colony’s calcium carbonate skeleton. Bryozoan colonies could grow into massive structures that provided habitat for other marine life, essentially serving as the apartment buildings of ancient reef communities. The diversity of bryozoan fossils in the Rockies is staggering, with some species creating delicate, net-like structures while others built robust, branching forms that could withstand strong ocean currents. These fossils might be small, but they played huge roles in ancient ecosystems, helping to build the complex three-dimensional reef structures that supported countless other species in prehistoric seas.

Fossilized Burrows: Traces of Invisible Life

Not all fossils in the Canadian Rockies are actual body parts – some of the most intriguing discoveries are trace fossils that show evidence of ancient animal behavior without preserving the animals themselves. These include fossilized burrows, feeding trails, and other marks left by creatures as they moved through the sediment on ancient seafloors. Paleontologists have found complex burrow systems that show how early marine worms and arthropods lived, fed, and sought shelter in the muddy bottoms of prehistoric seas. Some of these trace fossils reveal sophisticated behaviors, like spiral burrows created by ancient sea anemones or U-shaped tubes built by filter-feeding worms that are virtually identical to burrows made by modern marine animals. These traces give us unique insights into the daily lives of ancient creatures, showing us not just what they looked like, but how they behaved, what they ate, and how they interacted with their environment millions of years ago.

Sponge Reefs: Ancient Water Filters

The Canadian Rockies contain some of the world’s best-preserved examples of ancient sponge reefs, massive underwater structures built by colonial sponges that filtered enormous volumes of seawater every day. These prehistoric sponges were quite different from the simple bath sponges we know today – they were complex organisms that built rigid skeletons out of silica or calcium carbonate, creating towering reef structures that could be seen from great distances across the ancient seafloor. The fossilized sponge reefs found in the Rockies show incredible diversity, with some species building delicate, vase-shaped structures while others created massive, dome-shaped colonies that housed countless other marine creatures. These ancient filter-feeders played crucial roles in maintaining water quality in prehistoric seas, processing massive amounts of water and removing bacteria, algae, and organic particles just like modern sponges do today. The preservation of entire sponge reef communities in the Rocky Mountain formations gives scientists a rare opportunity to study how these important ecosystems functioned and evolved over millions of years.

Conodont Elements: Tiny Teeth, Big Discoveries

Some of the most important but least visible fossils in the Canadian Rockies are conodonts, microscopic tooth-like structures that belonged to mysterious early vertebrates that lived in ancient seas. These tiny fossils, often smaller than a grain of rice, are incredibly abundant in certain rock layers and have revolutionized our understanding of early vertebrate evolution and ancient ocean chemistry. Conodonts were part of feeding apparatus used by eel-like creatures that may represent some of the earliest vertebrates on Earth, and their rapid evolution makes them incredibly useful for dating rock formations and understanding ancient environments. The chemistry of conodont fossils can tell paleontologists about ancient ocean temperatures, sea levels, and even the chemistry of prehistoric seawater, making these tiny teeth some of the most scientifically valuable fossils found in the region. Despite their small size, conodonts have provided huge insights into the early evolution of vertebrates and the environmental conditions that existed in ancient seas millions of years ago.

Preserving the Past for the Future

Today, the fossil-rich formations of the Canadian Rockies face new challenges as climate change, erosion, and human activity threaten these irreplaceable windows into the past. Paleontologists and park officials work together to protect important fossil sites while still allowing scientific research and public education to continue. Many of the most significant discoveries, like those from the Burgess Shale, are now protected within national parks and UNESCO World Heritage Sites, ensuring that future generations will be able to study and appreciate these remarkable remnants of ancient life. The ongoing work of fossil hunters and researchers in the Canadian Rockies continues to yield new discoveries that challenge our understanding of early life on Earth and provide crucial data for understanding how ecosystems respond to environmental change. These ancient treasures remind us that the mountains we see today are just the latest chapter in a story that began hundreds of millions of years ago, when strange and wonderful creatures ruled the warm seas that once covered this majestic landscape.

The next time you find yourself hiking through the Canadian Rockies, take a moment to really look at the rocks beneath your feet and the cliff faces around you. You’re not just walking through some of the most beautiful scenery on Earth – you’re traveling through time itself, surrounded by the remains of creatures that lived and died in ancient seas so long ago that the very concept stretches our imagination. What other secrets do you think these mountains are still hiding?