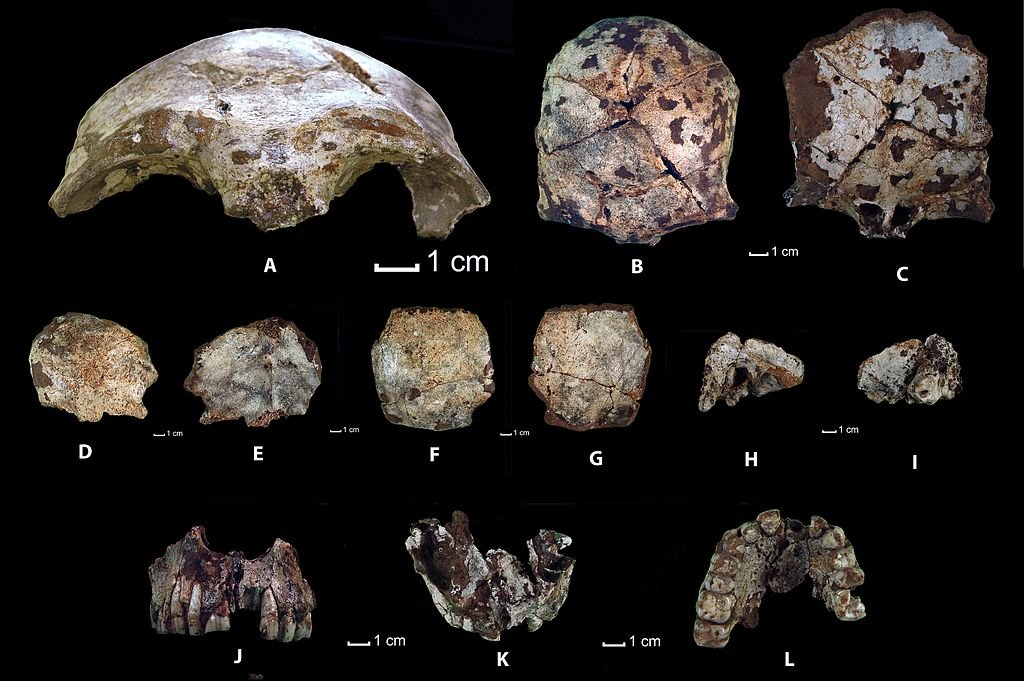

In an amazing turn of events, a large-scale land reclamation project in Indonesia has resurrected a lost world, rather than only sand. While workers were building off an artificial island off Java, they dragged 6,700 fossils from the seafloor, including two skull fragments of Homo erectus, our ancient human predecessors. These 140,000-year-old fossils expose a startling reality: the once-isolated Javanese Homo erectus population may have wandered far beyond their island base across a now-submerged savannah called Sundaland. The discovery questions accepted wisdom on early human migration, survival tactics, and even possible interactions with other hominin species including Neanderthal and Denisovans.

The Accidental Discovery: How Dredging Unlocked a Prehistoric Time Capsule

Between 2014 and 2015, contractors in Indonesia dredged 176.5 million cubic feet of sand from the Madura Strait to create a 250-acre artificial island near Surabaya. But as the sand settled, something unexpected emerged, thousands of ancient fossils. Among them were two Homo erectus skull fragments, marking the first time this species’ remains have been found between Indonesian islands rather than solely on Java.

Archaeologist Harold Berghuis, who led the study, described the moment he spotted the first skull fragment: “It was already getting dark, and I sat down to enjoy the sunset. Then, right beside me, lay this fossil that reminded me of the only Dutch Neanderthal ever found.” The fragment’s thick brow ridge confirmed it belonged to Homo erectus, a species that thrived for nearly 2 million years before vanishing.

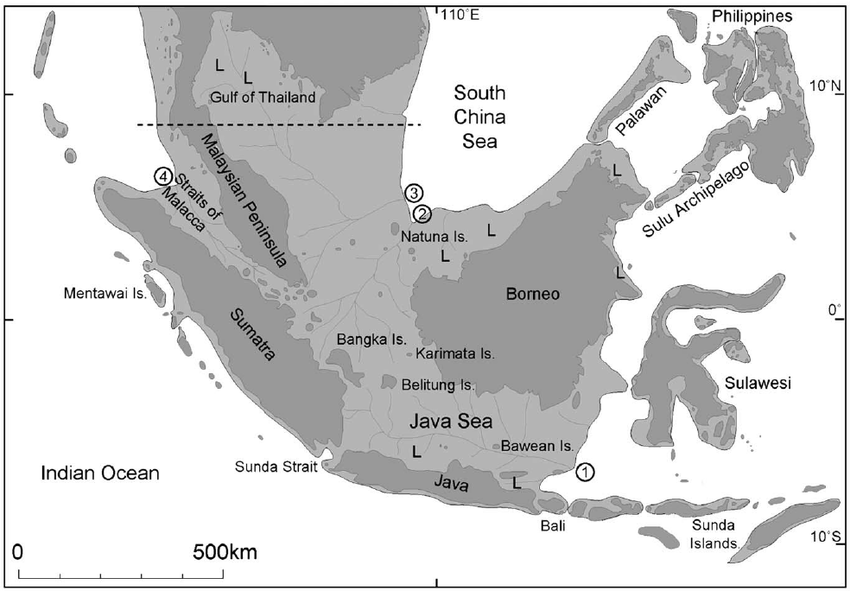

Sundaland: The African-Like Savannah That Once Connected Asia

The fossils were preserved in what was once a drowned river valley, part of a vast prehistoric landscape called Sundaland. During the last Ice Age, sea levels were 100 meters (328 feet) lower, exposing a sprawling savannah that linked present-day Indonesia’s islands to mainland Asia. This region, now submerged, resembled today’s African grasslands, with rivers teeming with fish, turtles, and even river sharks.

Homo erectus most certainly hunted megafauna elephants, rhinos, hippos, and Komodo dragons that Sundaland also hosted. Cut marks on turtle shells and broken bovid bones point to a behavior not seen in Javan H. erectus but rather typical of mainland hominids: they butchered huge game and extracted marrow. This begs an intriguing question: Did these early humans either learn from or even interbreed with other species?

A New Hunting Strategy: Was Homo erectus Copying Other Humans?

One of the most surprising findings was evidence that Homo erectus selectively hunted prime-aged bovids, a strategy associated with more advanced hominins like Neanderthals. “We didn’t find this in earlier Javan populations,” Berghuis noted, “but we see it in mainland groups. Did they learn from them?”.

This implies either genetic mixing or perhaps cultural interaction between H. erectus and other human species. Although DNA from these fossils is still not recovered, the behavioral similarities point to interactions hitherto unthinkable. Should confirmation, it would redefine our knowledge of early human networks in Southeast Asia.

The Last Stand of Homo erectus And Their Mysterious Extinction

Homo erectus was a remarkably successful species, surviving for 1.5 million years before disappearing around 108,000 years ago. The newly dated fossils place them in Sundaland just before their extinction, as climate shifts turned their savannah refuge into dense rainforests.

Recent studies suggest the last Javan H. erectus may have died in a “mass death event”, possibly due to floods or volcanic mudflows. “Their remains were washed downstream and caught in a logjam,” explains paleoanthropologist Kira Westaway. With their habitat vanishing, these resilient hominins finally met their end long before modern humans arrived in the region.

Why This Discovery Rewrites Human Prehistory

Scientists for decades thought Homo erectus lived alone on Java. These fossils, however, show they explored outside the island, adjusting to Sundaland rivers and grasslands. Furthermore suggested by the results are:

- Targeting big game, they were not simple scavengers but rather accomplished hunters.

- They might have interacted with other human species, so subverting the notion of total isolation.

- Their disappearance was probably environmental rather than resulting from conflict with contemporary people.

What Lies Beneath: The Future of Underwater Archaeology

The Madura Strait fossils are just the beginning. “The answers may very well be at the bottom of the sea,” the researchers write. With 95% of Sundaland still underwater, future dredging projects or dedicated underwater excavations could uncover more clues about early human migration, lost ecosystems, and even unknown hominin species.

Conclusion: A Ghost World Resurfaces

The Madura Strait fossils mark only the start. The researchers note, “the answers may very well be at the bottom of the sea.” Future dredging projects or committed underwater excavations may find more evidence about early human migration, lost ecosystems, and even unidentified hominin species among 95% of Sundaland still underwater.

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.