In the dry, sun-scorched hills of southern Italy, archaeologists dug up an odd artifact a terra cotta cup in the shape of the head of a savage Spartan hound, its mouth perpetually agape as if mid-bark. This 2,300-year-old rhyton, a ritual drinking cup, is a fascinating look into the noisy feasts and sacred rituals of ancient Greece. But this was no typical cup. Conceived to never lie flat, it compelled its consumer either to empty it at one sitting or spill its contents, a clever (or maybe wicked) variation that exposes how the ancients drew even the practice of revelry into the realm of ritual.

Now housed at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, this Laconian hound rhyton is more than a relic; it’s a portal to a world where wine flowed freely, satyrs cavorted on pottery, and every sip was an act of devotion or debauchery.

The Spartan Hound: A Hunter Immortalized in Clay

The rhyton takes the form of a Laconian hound, a now-extinct Greek breed revered for its speed and tenacity. Originating in Laconia the rugged homeland of Sparta these dogs were the ancient equivalent of elite hunting companions, celebrated in mosaics, tombstones, and, as this vessel proves, drinking cups.

Crafted around 340–320 B.C., the cup’s black glaze accentuates the hound’s alert ears and intense, diluted-glaze eyes. The choice of a hunting dog wasn’t arbitrary. In Greek culture, hounds symbolises loyalty, discipline, and the wild thrill of the chase qualities that resonated with Spartan warriors and symposia (drinking parties) attendees alike.

A Masterpiece from the Darius Painter’s Workshop

This rhyton wasn’t mass-produced. It bears the hallmarks of the Darius Painter, a prolific Apulian artisan whose workshop dominated southern Italy’s ceramic scene. Known for intricate mythological scenes, the painter adorned this cup with a satyr a half-goat, half-man creature holding a plate and staff, framed by delicate leaf and egg motifs.

The satyr’s presence is telling. These rowdy followers of Dionysus, the god of wine, were synonymous with excess. Their inclusion suggests this rhyton wasn’t just for sipping; it was a prop in performances of myth, where drinkers might channel divine madness with every pour.

No Flat Bottom, No Mercy: The Rules of Ancient Drinking

Unlike today’s mugs, rhytons were not allowed to be put down. Curved at the base, drinkers would have to guzzle or spill a masterful design that allowed the wine (or blood) to continue circulating. Such an aspect must have made drinking games endurance trials with players trying to empty their cups without spilling a drop.

The tradition may have roots in Bronze Age Eurasia, where animal-horn cups were common. But the Greeks added their own flair, replacing simple horns with elaborate animal and mythical forms. From griffins to rams, each rhyton carried symbolic weight, transforming a simple vessel into a storyteller.

Wine, Blood, and Divine Offerings

While rhytons starred at symposia, their use extended beyond party tricks. Archaeologists believe they played a role in libations ritual offerings of wine, oil, or even blood to the gods. In sacrifices, a rhyton might have been used to pour liquids onto altars, linking the communal act of drinking to divine communion.

The Laconian hound’s presence hints at deeper meanings. Was it a nod to Artemis, the huntress goddess? Or a tribute to fallen warriors, whose dogs were often buried beside them? Either way, this cup was more than decor it was a bridge between the mortal and the mystical.

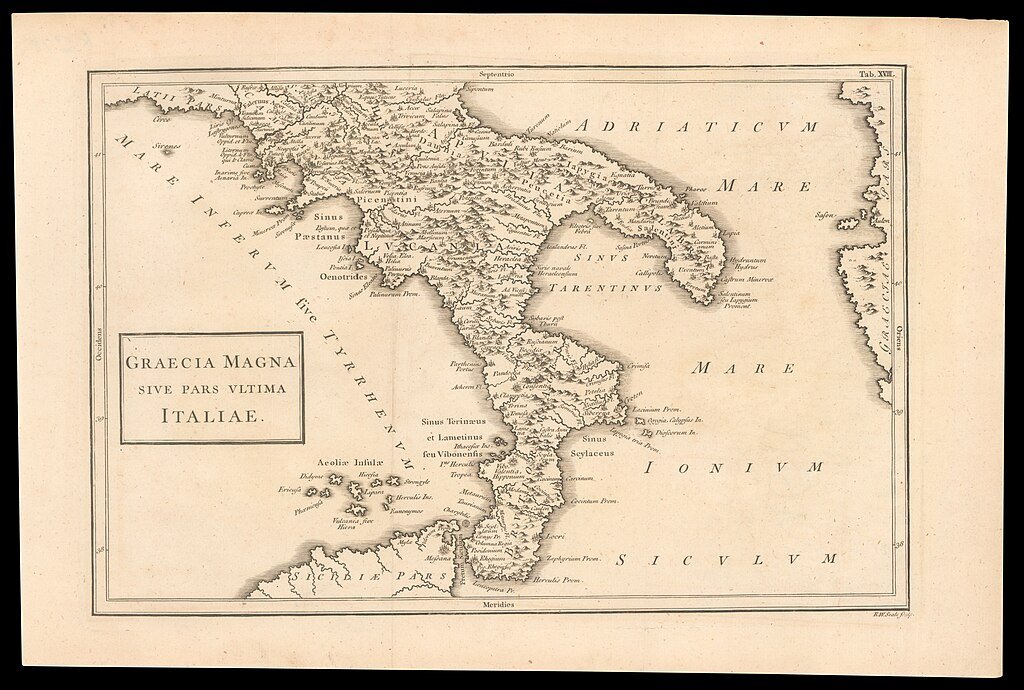

Magna Graecia: Where Greek Culture Thrived Beyond Greece

This rhyton wasn’t found in Athens or Sparta, but in Puglia, the “heel” of Italy’s boot. By the 4th century B.C., this region was part of Magna Graecia (“Greater Greece”), a network of colonies so deeply Hellenized that their art, language, and rituals rivaled the mainland’s.

The workshop of the Darius Painter thrived here, mixing Greek myths with the local palate. The discovery of the rhyton highlights just how much Greek culture had invaded the Mediterranean long before Rome gained dominance. Not until 205 B.C. did the region come under Roman rule, yet finds such as this demonstrate that Greek influence lingered.

Why This Rhyton Still Captivates Us

Today, the Getty’s Laconian hound rhyton is more than a museum piece. It’s a testament to the hedonism and spirituality of ancient life, where every cup told a story, every sip a ceremony. Its unyielding design forcing drinkers to commit or forfeit mirrors the Greek ethos: life, like wine, was to be consumed boldly.

So the next time you raise a glass, imagine holding this Spartan hound, its satyr grinning as if to say: Drink deeply. The gods are watching.

Final Thought:

This rhyton didn’t just hold wine it held a worldview. In its curves and glazes, we see the wild heart of ancient Greece, where even a dog-shaped cup could be a vessel for myth, memory, and a very good party.

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.