It’s a sight that stirs hearts and sparks outrage across the world: dolphins herded into a shallow cove, their sleek bodies splashing in frantic confusion as a handful of people prepare for a practice as old as some traditions and as controversial as any modern debate. Why do dolphin hunts still happen in Japan, a country renowned for its relationship with the sea? And who are the brave souls raising their voices to end this practice? The answers are tangled in centuries of culture, economics, science, and activism, weaving a story as complex and captivating as the creatures themselves.

The Ancient Roots of Dolphin Hunting in Japan

Dolphin hunting in Japan stretches back over 400 years, long before the world’s eyes turned to the small coastal town of Taiji. In earlier times, fishing communities saw dolphins as both competitors for fish and valuable sources of food and materials. The techniques were passed down like family heirlooms, and dolphin meat became a staple in some regions. For these communities, the hunt wasn’t just about survival; it was a ritual that bound people together. Even today, some defenders see it as a precious thread in their cultural tapestry, making the issue feel deeply personal and fiercely defended.

Taiji: The Heart of Modern Dolphin Hunts

When most people think of Japanese dolphin hunts, they picture Taiji, a town on the Kii Peninsula. Every year, from September to March, its cove becomes the focal point of international attention. Fishermen drive pods of dolphins into the bay, where some are selected for sale to marine parks and aquariums, while others are killed for meat. The spectacle is both shocking and surreal, drawing activists, media, and tourists alike. Taiji’s identity has become inseparable from the hunts, creating tension between locals and outsiders who demand change.

Economic Motivations Behind the Hunts

Dolphin hunting isn’t just about tradition; it’s also about money. The sale of live dolphins to aquariums, especially overseas, can fetch tens of thousands of dollars per animal. While the meat market has declined due to health concerns and changing tastes, the live trade remains lucrative. For a small town like Taiji, these earnings provide jobs and support local businesses. Fishermen argue that the hunt keeps their community afloat, making the calls for an outright ban feel like a threat to their very way of life.

The Science of Dolphins: Intelligence and Social Bonds

Dolphins are celebrated for their intelligence, complex social structures, and playful behavior. Scientists have documented their ability to solve puzzles, communicate with whistles and clicks, and even recognize themselves in mirrors—a sign of self-awareness. Many researchers believe their tight-knit pods are more like families, with members caring for each other in ways that seem almost human. This scientific understanding has fueled arguments against the hunts, with people questioning the morality of killing such sentient beings.

International Outcry and Media Attention

The world’s gaze turned sharply to Japanese dolphin hunts after documentaries like “The Cove” exposed the drama and violence of the events. Social media amplifies every image and story, sparking global protests and online campaigns. Celebrities, scientists, and animal welfare groups have all weighed in, calling for an end to the hunts. For many, the issue has become a symbol of humanity’s evolving relationship with wildlife, raising uncomfortable questions about tradition versus compassion.

Japanese Perspectives: Culture, Sovereignty, and Resistance

Within Japan, opinions on dolphin hunting are far from unanimous. Some see it as a relic of the past, best left behind. Others, especially in hunting communities, view outside criticism as cultural imperialism—a foreign attempt to erase their traditions. The Japanese government has often defended the hunts on grounds of cultural heritage and food security, asserting the right to manage their own resources. This clash of perspectives makes the path to change far from straightforward.

The Role of Animal Welfare Organizations

Groups like Sea Shepherd, Dolphin Project, and the World Wildlife Fund have made it their mission to stop dolphin hunts in Japan. Their tactics range from peaceful protest and undercover filming to international lobbying and education campaigns. These organizations work tirelessly to bring global attention to the issue, sometimes risking arrest or harassment. Their efforts have led to tighter scrutiny and, in some cases, smaller catches, but the core practice remains deeply entrenched.

Legal Frameworks and Loopholes

Japan’s laws allow for dolphin hunting under certain quotas, set by government agencies. These quotas are supposed to ensure that populations remain stable, but critics argue that data is incomplete and that enforcement is weak. International agreements like the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) place restrictions on trading certain dolphin species, but loopholes and limited oversight mean that live trade continues. Legal battles over these rules are ongoing, with activists pushing for stricter protection.

Dolphin Meat: Health Concerns and Declining Demand

Dolphin meat was once a local delicacy in parts of Japan, but its popularity has nosedived in recent years. Scientists have found high levels of mercury and other toxins in dolphin flesh, raising serious health concerns. Public awareness campaigns and shifting dietary habits have further reduced demand. In some areas, dolphin meat is now mostly consumed by older generations, while younger people often avoid it altogether.

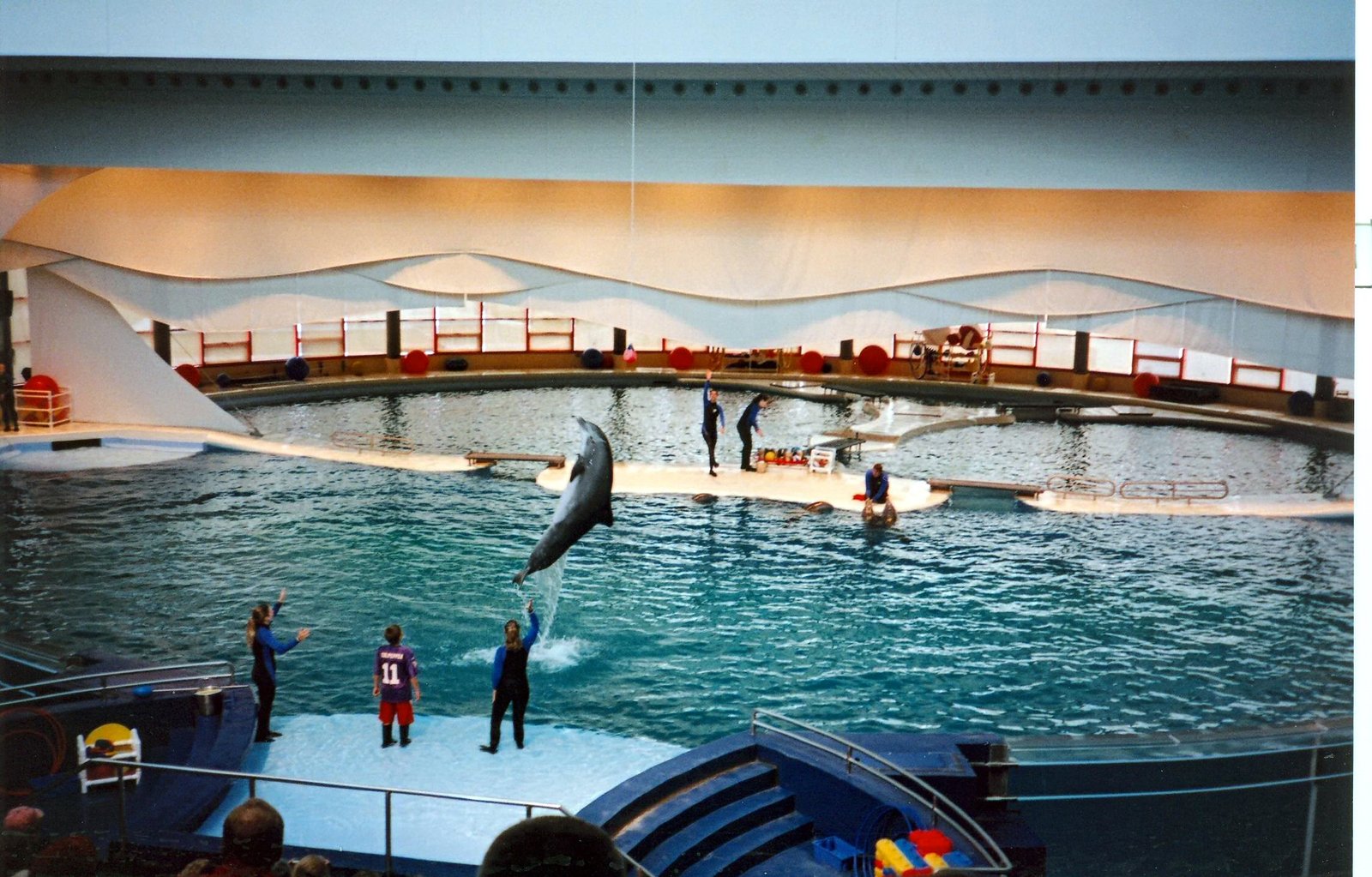

The Captivity Trade: From Ocean to Aquarium

A significant portion of dolphins captured in Taiji don’t end up on dinner plates—they’re sold to marine parks and aquariums worldwide. Trainers select the most “attractive” animals, which are then shipped to facilities in Asia, the Middle East, and sometimes even Europe. This trade is highly profitable, but it raises ethical questions about keeping such intelligent creatures in confinement. Some aquariums have pledged to stop buying wild-caught dolphins, but the market remains stubbornly resilient.

Impact on Local Ecosystems and Fisheries

Dolphin hunting doesn’t just affect the animals themselves—it has ripple effects throughout the marine ecosystem. Removing large numbers of dolphins can disrupt food webs, potentially leading to overpopulation of certain fish or squid. Ironically, fishermen sometimes see dolphins as competitors, blaming them for declining catches. However, marine biologists warn that destabilizing dolphin populations may backfire, leading to even greater imbalances in the long run.

Public Opinion in Japan: A Changing Tide?

Surveys suggest that many Japanese people are either unaware of the dolphin hunts or have mixed feelings about them. Urban residents, in particular, tend to oppose the practice or see it as outdated. Grassroots campaigns and educational efforts are slowly shifting attitudes, especially among young people. Still, change is slow, and deep-rooted social and economic factors mean that outright opposition is rare in hunting towns.

Technological Advances and Monitoring Efforts

New technology has brought unprecedented transparency to dolphin hunts. Drones, GPS trackers, and live-streaming have allowed activists to document what happens in real time, putting pressure on authorities and fishermen alike. Satellite data and DNA analysis are helping scientists better understand dolphin populations and migration patterns, which could lead to more informed management. Technology is becoming a powerful tool in the fight for dolphin welfare.

Educational Outreach and School Curricula

Some Japanese schools have begun to include lessons on marine biodiversity and conservation, exposing students to the ethical debates surrounding dolphin hunting. Environmental groups visit classrooms, run workshops, and distribute literature to raise awareness. These efforts aim to nurture empathy and critical thinking in the next generation, planting seeds that could one day grow into broader societal change.

Aquariums and Zoos: Changing Policies and New Ethics

In response to international pressure, a growing number of Japanese aquariums have pledged to stop buying dolphins caught in the wild. The Japanese Association of Zoos and Aquariums (JAZA) even suspended its ties with Taiji for a time, signaling a shift in industry standards. Some facilities are now investing in rescue and rehabilitation programs, focusing on education rather than entertainment. The tide may be slowly turning, but old habits die hard.

The Power of Documentary Filmmaking

Few things have galvanized the anti-hunt movement like powerful documentaries. “The Cove” won an Oscar and catapulted Taiji into the world’s consciousness. Filmmakers risked their safety to capture the secretive events, using hidden cameras and night-vision gear. These films don’t just inform—they provoke outrage, empathy, and action. For many viewers, the images are impossible to forget, fueling petitions, protests, and political pressure.

Grassroots Activism and Local Heroes

Not all opposition comes from abroad. Japanese activists—many of them young and passionate—are raising their voices from within. Some organize peaceful demonstrations in Taiji, while others focus on social media campaigns or art projects. Local leaders who speak out often face hostility or ostracism, but their courage inspires others. These grassroots efforts are vital, slowly chipping away at the wall of tradition.

New Approaches: Ecotourism and Alternatives

Some forward-thinking communities are exploring alternatives to dolphin hunting. Ecotourism—where visitors come to watch dolphins in the wild rather than see them in captivity or on a plate—is gaining ground. Tour operators work with local fishermen to offer boat rides and educational experiences, turning “hunters” into guides. While not a silver bullet, ecotourism offers a way to preserve culture while protecting dolphins.

The Road Ahead: Uncertainty and Hope

The future of dolphin hunts in Japan hangs in the balance. Economic pressures, shifting public opinion, and relentless activism all tug the issue in different directions. While the pace of change can feel glacial, history shows that cultural shifts often begin quietly, then accelerate. The resilience of the dolphins themselves—a symbol of intelligence and grace—reminds us what’s at stake. Will the next generation look back and see this as a turning point?

The fate of Japan’s dolphins, and the communities that have relied on them, remains uncertain. But in the collision of tradition, science, and activism, the world is watching—and the story is far from over.