Imagine gliding through the clear water of a river, sunlight shimmering above, when suddenly—a sharp hook pierces your mouth. For centuries, humans have wondered: in that solitary moment, does a fish feel pain, or is it an unfeeling creature, incapable of suffering? The question stirs deep emotion and debate, stirring up both scientific curiosity and ethical reflection. The idea that fish might experience something akin to pain challenges how we view the underwater world and our place within it. Understanding whether fish feel pain doesn’t just reshape our scientific perspective; it also asks us to reconsider our everyday choices and the silent struggles happening beneath the surface. Let’s dive into the mysterious and often overlooked reality of fish sentience.

The Anatomy of Fish: Are They Built to Feel Pain?

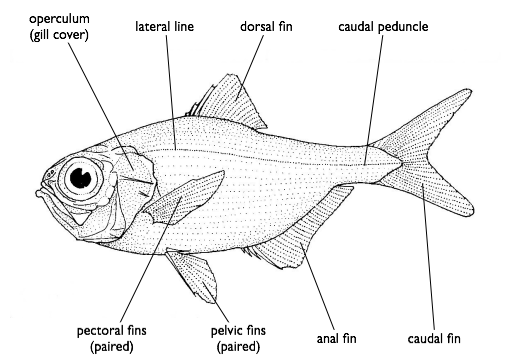

Fish may look very different from us, but their bodies hold surprising complexity. Unlike mammals, fish don’t have a neocortex—the part of the brain humans use to process pain. Still, fish possess nociceptors, which are specialized nerve endings that detect potentially damaging stimuli. These receptors are found in their skin, lips, and mouths, allowing fish to sense harm. When you watch a fish react to a sharp object or a sudden hot spot in the water, you might notice it flinch or swim away, suggesting some kind of sensory awareness. But just having the biological hardware isn’t quite enough to say fish truly feel pain. Scientists look deeper, exploring what happens in a fish’s body and brain when it gets hurt. The real question is, do these signals translate into conscious suffering, or are they simply automatic responses?

What Is Pain? Defining an Elusive Experience

Pain is more than just a physical reaction—it’s an experience that combines sensation and emotion. For humans, pain isn’t only about nerves firing; it’s about feeling distress, fear, or discomfort. This emotional aspect is what makes pain so hard to measure in animals, especially fish. Since fish can’t tell us how they feel, researchers look for clues in their behavior and brain activity. Some scientists argue that for pain to be “real,” an animal must be aware of it and not just react automatically. This definition raises the stakes: if fish can feel pain emotionally, it transforms how we think about their welfare. The debate continues, with some researchers pushing for a broader, more inclusive view of animal suffering.

Fish Brains: Simple or Surprising?

At first glance, a fish’s brain looks tiny and primitive compared to those of mammals. But appearances can be deceiving. Studies using advanced imaging have revealed that fish brains light up in response to painful stimuli, sometimes in areas similar to those involved in pain in other animals. For example, when a fish is injured, certain chemicals and electrical signals are released, mirroring what happens in more complex creatures. This suggests that, while simpler, fish brains are still capable of processing complex sensory information. The debate rages on in scientific circles: are these brain responses enough to prove real suffering, or are they just basic survival mechanisms? For many researchers, the evidence is growing that fish brains may be more sophisticated than we ever imagined.

Behavioral Clues: How Fish React to Harm

If you’ve ever watched a fish after it’s been hooked and released, you might notice it behaving differently—swimming erratically or avoiding food for hours or even days. These changes aren’t just random. Scientists have observed fish rubbing injured areas against objects, similar to how a dog might lick a wound. In laboratory studies, fish given a painful stimulus often show altered patterns: they may become less active, hide more, or avoid places where they’ve been hurt before. These behaviors suggest that fish remember negative experiences and act to avoid them, a sign of learning and awareness. Such evidence challenges the idea that fish are simple, instinct-driven creatures with no real feelings.

Do Fish Have Emotions?

The notion that fish might have emotions can feel startling. Yet, research hints at a spectrum of feelings beneath the surface. Some experiments show that fish can become stressed, anxious, or even depressed when isolated or exposed to chronic pain. For instance, zebrafish display signs of anxiety when placed in unfamiliar environments, and their behavior changes with stress or injury. While their emotions might not mirror human feelings exactly, these patterns point toward a kind of inner life. The possibility of emotional pain in fish forces us to think more deeply about their needs and experiences.

Comparing Fish and Mammal Pain Responses

Comparisons often help us understand the unfamiliar. When fish and mammals are exposed to similar injuries, both react in ways that suggest discomfort: changes in heart rate, hormone release, and efforts to protect injured areas. However, fish may not vocalize or show facial expressions like mammals do, making their suffering easier to overlook. Still, the physiological similarities are striking. Painkillers such as morphine reduce signs of distress in both fish and mammals, supporting the idea that both groups share fundamental pain pathways. This overlap blurs the line between “simple” and “complex” animals, urging us to reconsider old assumptions.

The Ethical Dilemma: What Does It Mean If Fish Feel Pain?

If fish do feel pain, our entire relationship with them comes under scrutiny. Every year, billions of fish are caught, farmed, and killed for food, often without protections that mammals receive. Many fishing methods, like trawling or live baiting, would be considered cruel if used on land animals. Accepting fish pain as real raises tough questions about fishing, aquaculture, and even the way we keep pet fish. Some countries have begun to introduce welfare guidelines for fish, but practices vary widely. The ethical implications are profound, touching on everything from food choices to conservation efforts.

Fishing and Angling: Tradition Meets Science

For many, fishing is a beloved tradition, a peaceful pastime that connects people to nature. But as science uncovers more about fish sentience, some anglers are rethinking their methods. Catch-and-release, once seen as humane, may still cause stress and injury to fish. Others advocate for the use of barbless hooks, wet hands, and quick releases to minimize suffering. These changes reflect a growing awareness that our actions have real consequences for creatures we once thought unfeeling. The fishing community finds itself at a crossroads, balancing cultural heritage with newfound responsibility.

Fish Farming: The Silent Majority

Fish farming, or aquaculture, supplies much of the world’s seafood, but often takes place out of sight. On crowded fish farms, injuries and disease can spread quickly, raising concerns about unseen suffering. Stress and pain can affect the health and growth of farmed fish, impacting not just their welfare but the quality of food produced. Some farms now use anesthesia during handling or slaughter, while others redesign tanks to reduce injuries. These steps show that even in large-scale operations, attention to fish pain is slowly gaining ground. The silent majority of fish in aquaculture may one day see their struggles better recognized.

Scientific Skepticism and Ongoing Debates

Despite mounting evidence, not all scientists agree that fish truly feel pain. Some argue that fish lack the brain structures necessary for conscious suffering, interpreting their reactions as mere reflexes. Others point out gaps in research or call for more rigorous experiments. This skepticism is critical for science, pushing researchers to refine methods and seek clearer answers. The debate is far from settled, but the conversation itself reflects a new respect for fish as subjects of scientific inquiry. As research continues, our understanding of fish sentience will likely evolve, revealing even more surprises beneath the surface.

Changing Perspectives: What Can We Learn from Fish?

Learning about fish pain isn’t just about the animals—it’s about us. It challenges our assumptions, asking us to look beyond appearances and recognize the hidden lives around us. As we discover more about fish sentience, we’re reminded that intelligence and feeling come in many forms, not just those familiar to humans. These revelations can inspire greater compassion, not just toward fish, but to all creatures who share our planet. In a world where every living thing faces its own silent struggles, perhaps the greatest lesson is to listen more carefully, even when the voices are hard to hear.