Deep in the heart of California’s Death Valley, where temperatures soar to 134°F and the ground sits nearly 300 feet below sea level, life shouldn’t exist. Yet beneath the blindingly white salt flats and crystalline formations of Badwater Basin, something extraordinary is happening. This isn’t just a barren wasteland — it’s a thriving metropolis of microscopic life forms that have mastered the art of survival in one of Earth’s most punishing environments.

The Invisible Champions of Badwater Basin

When you stand on the salt flats of Death Valley, you’re actually standing on top of one of the most extreme ecosystems on our planet. Microscopic organisms called extremophiles thrive in these brutal conditions. These tiny warriors don’t just survive — they flourish in temperatures that would cook most life forms, in salt concentrations that would pickle anything else, and in conditions so harsh that scientists study them to understand what life might look like on Mars. The ground beneath your feet is alive with bacteria, archaea, and other microorganisms that have rewritten the rules of biology. Just underneath the salt, the soil teems with communities of microbes. It’s like discovering an entire civilization in your backyard that you never knew existed. Each grain of salt, each crystal formation, each seemingly lifeless patch of ground hosts communities of organisms that have evolved strategies so ingenious they make our greatest survival stories look like child’s play.

The Magnetotactic Marvel: BW-1

In 2011, scientists made a discovery that changed everything we thought we knew about Death Valley’s microscopic residents. In a basin named Badwater on the edge of Death Valley National Park, Bazylinski and researcher Christopher Lefèvre hit pay dirt. They found something that seemed almost too strange to be real: a bacterium that could swim through water by following magnetic fields like a living compass needle. It has been labeled strain BW-1. This remarkable microbe doesn’t just navigate by magnetism — it actually produces its own magnetic crystals inside its tiny body. Researchers found the greigite-producing bacterium, called BW-1, in water samples collected more than 280 feet below sea level in Badwater Basin. Lefèvre and Bazylinski later isolated and grew it leading to the discovery that BW-1 produces both greigite and magnetite. What makes BW-1 even more special is that it can produce two different types of magnetic minerals, making it unique among all known magnetotactic bacteria. It’s like having a Swiss Army knife at the cellular level.

The Salt-Loving Halophiles

Halophiles are extremophilic microorganisms that can grow optimally in saline and hypersaline environments, such as deep-sea sediments, saline lakes, salt pans, saline soils, and sea water, and Death Valley’s salt flats are their paradise. These organisms have developed extraordinary adaptations to not just tolerate but require high salt concentrations that would be deadly to most life forms. Think of them as the ultimate pickle-lovers of the microbial world. They’ve evolved special proteins that actually work better in salty conditions, and some even use salt as a source of energy. Despite this high salinity, many organisms not only survive, but thrive here. The pool is home to an endemic snail naturally found only at this location, and its rim is dotted with salt tolerant plants, including pickleweed. These halophiles are so adapted to their salty environment that placing them in fresh water would actually kill them — it’s the complete opposite of what we’d expect from life on Earth.

Heat-Resistant Thermophiles

When Death Valley’s surface temperatures hit record-breaking highs, most life forms would literally cook. But thermophiles thrive in these conditions that would make a sauna feel like a cool breeze. Thermophiles have enzymes known as thermozymes, which are catalytically active at high temperatures. Surprisingly, amino acid contents, protein sequences and the structure of thermozymes are quite similar to mesophilic enzymes, which function optimally between (25 and 35 °C). These remarkable microbes have essentially redesigned their cellular machinery to work at temperatures that would denature the proteins in our bodies. Their enzymes are like molecular machines built to withstand extreme heat, with special structural features that keep them stable when the going gets tough. Some of these organisms can survive temperatures over 200°F, making Death Valley’s summer heat feel almost comfortable by comparison. Structural features in these enzymes, such as unique salt bridges, extensive hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions are thought to function as stabilizing forces that enable their thermophilicity. It’s molecular engineering at its finest, perfected over millions of years of evolution.

The Acid and Alkaline Specialists

Death Valley’s extreme pH conditions would burn through most living things, but specialized extremophiles have made these harsh chemical environments their home. The organisms may be described as acidophilic (optimal growth between pH 1 and pH 5); alkaliphilic (optimal growth above pH 9), and Death Valley hosts both types in different microenvironments. Some areas of the valley are so alkaline they’re like living in liquid soap, while others are acidic enough to dissolve metal. Yet these microbes have evolved to not just survive but prefer these conditions. They’ve developed special cellular pumps and protective mechanisms that allow them to maintain their internal chemistry while dealing with external conditions that would be lethal to almost any other life form. The data on the chemical analysis of the Death Valley soil indicated that the sediment sample was alkaline with a pH value of 9.51. Think of them as the ultimate chemical engineers, working in conditions that would shut down any factory on Earth. Their existence challenges our very definition of what constitutes a livable environment.

Radiation-Resistant Survivors

The high altitude and thin atmosphere of Death Valley expose its microbial residents to intense ultraviolet radiation that would quickly kill most organisms. But some extremophiles have evolved to actually thrive under these conditions. Initially, researchers attributed the radiophily to highly accurate DNA repair mechanisms. However, further studies established that Deinococcaceae members can regulate their metabolism by expressing cellular detoxifying genes. These remarkable organisms have developed multiple strategies for dealing with radiation damage, including incredibly efficient DNA repair systems and protective molecules that shield their cellular components. Further, some radiophiles synthesize small-molecule proteome shields that prevent protein degradation under radiation. In recent years, research on Deinococcus radiodurans has revealed the synthesis of novel proteins that are intrinsically resistant to oxidative damage. Some of these bacteria are so resistant to radiation that they could potentially survive in space, making them prime candidates for understanding how life might spread between planets. They’re like biological superheroes with radiation-proof costumes built right into their DNA.

The Pressure-Loving Piezophiles

While Death Valley might seem like a low-pressure environment, the microscopic world within salt crystals and deep sediments creates high-pressure conditions that have given rise to specialized piezophiles. The organisms may be described as acidophilic (optimal growth between pH 1 and pH 5); alkaliphilic (optimal growth above pH 9); halophilic (optimal growth in environments with high concentrations of salt); thermophilic (optimal growth between 60 and 80 °C [140 and 176 °F]); hyperthermophilic (optimal growth above 80 °C [176 °F]); psychrophilic (optimal growth at 15 °C [60 °F] or lower, with a maximum tolerant temperature of 20 °C [68 °F] and minimal growth at or below 0 °C [32 °F]); piezophilic, or barophilic (optimal growth at high hydrostatic pressure). These organisms have evolved to thrive under crushing pressure that would collapse ordinary cells. Their cell walls and membranes are reinforced to withstand pressures that would turn regular bacteria into cellular pancakes. They represent a type of life that could potentially exist in the deep subsurface of planets like Mars, where high pressure and extreme conditions might actually favor their survival. These microbes have essentially learned to use pressure as a tool rather than seeing it as an obstacle, turning what would be a death sentence for most life into a comfortable living environment.

Dormancy and Resurrection Masters

One of the most incredible survival strategies employed by Death Valley’s extremophiles is their ability to essentially “pause” their lives during the harshest conditions and then resurrect themselves when things improve. Dating back to more than 40 million years ago, extremophiles have continued to thrive in the most extreme conditions, making them one of the most abundant lifeforms. These organisms can enter states of dormancy so complete that they show no signs of life whatsoever, yet they can spring back to full activity when conditions become favorable. Some can survive in this state for decades, or even centuries, waiting for the right moment to return to active life. It’s like having a biological pause button that allows them to skip over the worst parts of environmental catastrophes. Survivors to date include spores of Bacillus subtilis and halophiles in the active (vegetative) state. Scientists have found bacteria that survived being frozen in Antarctic ice for thousands of years, only to wake up and start reproducing as if nothing had happened. This ability to cheat death makes them some of the most resilient organisms on our planet.

The Polyextremophiles: Masters of Multiple Stresses

The most impressive extremophiles in Death Valley don’t just tolerate one extreme condition — they’ve mastered multiple stresses simultaneously. Some extremophiles are adapted simultaneously to multiple stresses (polyextremophile); common examples include thermoacidophiles and haloalkaliphiles. These super-survivors deal with combinations of extreme heat, high salt, intense radiation, and toxic chemistry all at once. They’re like the Navy SEALs of the microbial world, trained to handle whatever harsh conditions get thrown at them. Microbes that have adapted to live in these environments have developed ways to thrive under multiple prominent stressors. Think of trying to survive in a place that’s simultaneously burning hot, incredibly salty, bathed in deadly radiation, and chemically toxic — that’s just another day at the office for these remarkable organisms. Their cellular machinery has been redesigned from the ground up to handle this combination of extreme stresses that would quickly kill any other form of life. They represent evolution’s ultimate solution to the problem of surviving in truly hostile environments.

Metabolic Mavericks and Energy Innovation

Death Valley’s extremophiles have rewritten the rules about how life can generate energy. While most life forms rely on conventional methods like photosynthesis or consuming organic matter, these innovative microbes have discovered entirely new ways to power their cellular processes. Meanwhile, a team from Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge has identified a type of archaea called Halobacteriales that can “breathe” carbon monoxide in the presence of these strongly oxidizing salts. Some use chemicals that would be toxic to other organisms as their primary energy source, essentially eating poison for breakfast. Others have learned to harvest energy from the breakdown of minerals in the salt flats, turning the very rocks around them into fuel. Extremophiles can thrive on perchlorates and metabolize carbon monoxide, researchers report. These metabolic innovations are so unique that they’re giving scientists ideas for new biotechnology applications, from cleaning up environmental contamination to producing useful chemicals in industrial processes. They’ve essentially become living chemical factories that can operate under conditions no human-designed system could handle.

The Mars Connection: Astrobiology Implications

The extremophiles of Death Valley aren’t just fascinating in their own right — they’re our best window into understanding what life might look like on other planets. Steering her gaze away from the heavens and downward into the salt-encrusted mud of Death Valley’s salt pan, Dr. Douglas is finding that the bacteria living there may provide clues to extraterrestrial life. Mars, with its extreme cold, high radiation, and toxic soil chemistry, might seem impossibly hostile to life as we know it. But the organisms thriving in Death Valley show us that life can adapt to conditions far more extreme than we ever imagined. If ever there was life on Mars, traces of it may be locked in the minerals formed in those long-gone waters. Scientists are studying these extremophiles to understand the outer limits of life’s adaptability and to design better instruments for detecting life on other worlds. She has recently discovered that the evaporites produced by the tiny extremophiles have an unusual structure, unlike anything a geologic process would naturally produce on Earth. Having identified the “signature” of Death Valley’s microorganisms, she is now hoping that through the use of remote satellite techniques, similar mineral signatures may be identified on Mars. The techniques being developed to study Death Valley’s hidden biosphere could one day help us discover whether we’re alone in the universe.

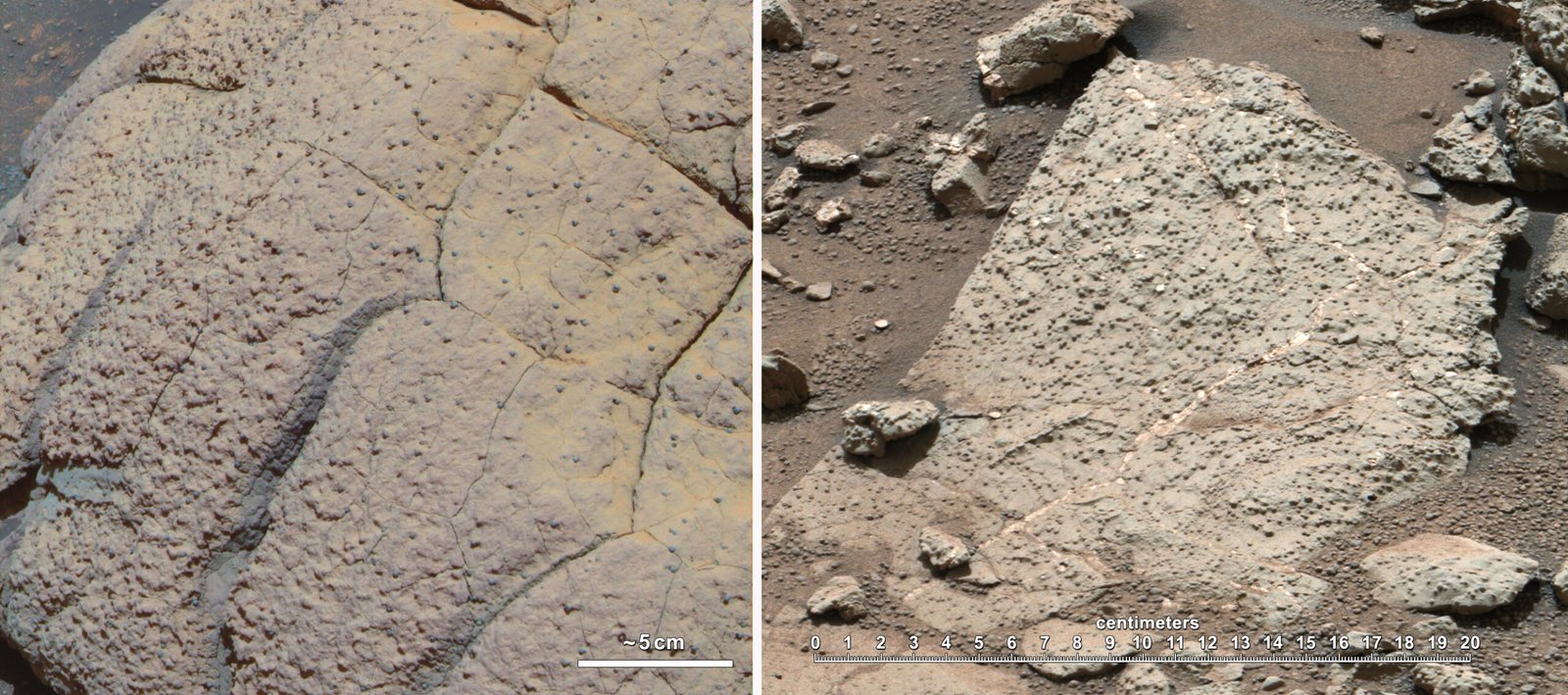

Biogeochemical Engineers

The extremophiles of Death Valley aren’t just passive survivors — they’re active engineers that reshape their environment on a massive scale. Sometimes they are produced through geologic processes, but they may also form as by-products of living organisms, such as the microbes at Badwater. These tiny organisms are constantly interacting with the minerals around them, dissolving some compounds while precipitating others, essentially acting as microscopic miners and builders. They create unique mineral formations that can only be produced by biological processes, leaving behind signatures of their activity that persist long after the organisms themselves have moved on. Some of these microbial mineral formations are so distinctive that they could serve as biosignatures — evidence of life that could be detected even on other planets. Halophilic microbial extremophiles provide energy and nutrient turnover for the system. Their activities help cycle nutrients through the ecosystem, making essential elements available to other organisms in forms they can use. They’re like tiny chemical engineers working around the clock to maintain the delicate balance that allows life to persist in one of Earth’s most challenging environments.

The Mesquite Flats Community

Beyond Badwater Basin, the sand dunes and rocky outcrops of Death Valley’s Mesquite Flats harbor their own unique communities of extremophiles. Pilot sequencing of cloned 16S rRNA genes identified Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria as the major bacterial groups present in this severe environment. This area represents a different type of extreme environment where organisms must deal with shifting sands, temperature fluctuations, and limited water availability. We found that 36 % of the sequences contained no significant identity (e-value >10−3) with sequences in the databases. The bacterial communities here are so unique that more than a third of the species found haven’t been seen anywhere else on Earth, suggesting that each extreme environment in Death Valley has fostered its own evolutionary innovations. These sand-dwelling extremophiles have developed strategies for surviving in an environment that’s constantly changing, where their entire world can be rearranged by a single windstorm. Mesquite Flats, an extreme environment that resides just south of the Cottonwood Mountains in Death Valley National Park, is home to hundreds of ephemeral sand dunes that have average crests of remarkable bacterial diversity. They represent evolution’s solution to surviving in a landscape that offers no permanent refuge and no guarantee of stability.

Biotechnology Goldmine

The extremophiles of Death Valley aren’t just scientific curiosities — they’re potentially the source of revolutionary biotechnology applications that could transform medicine, industry, and environmental cleanup. These creatures hold great promise for genetically based medications and industrial chemicals and processes. The unique enzymes produced by these organisms, called extremozymes, remain stable and active under conditions that would destroy conventional biological molecules. Extremozymes are useful in industrial production procedures and research applications because of their ability to remain active under the severe conditions (e.g., high temperature, pressure, and pH) typically employed in these processes. Industries are already using some of these enzymes in processes that require high temperatures, extreme pH, or other harsh conditions that would shut down normal biological systems. Medical imagery and drug delivery are just two of the technologies that benefit from this. The magnetic bacteria like BW-1 could revolutionize targeted drug delivery, allowing doctors to guide medications directly to specific parts of the body using magnetic fields. Greigite is an iron sulfide that may be superior to magnetite in some applications due to its slightly different physical and magnetic properties. Now we have the opportunity to find out. These applications represent just the beginning of what might be possible as we learn to harness the remarkable capabilities of Death Valley’s extremophiles.

The Hypolithic Hidden World

Some of Death Valley’s most remarkable extremophiles live in a secret world hidden beneath translucent rocks scattered across the desert floor. These cyanobacteria, which are able to convert sunlight into energy, are called hypoliths and have adapted to conditions too harsh for most other organisms. These organisms have found the perfect compromise between protection and access to sunlight by colonizing the underside of quartz rocks, which act like natural greenhouses and shielding them from the desert’s extreme temperatures and intense ultraviolet radiation while still allowing enough light to penetrate for photosynthesis. This unique microhabitat provides just enough moisture from dew and condensation to sustain life, enabling hypoliths to persist where survival seems nearly impossible, revealing the astonishing resilience of life in one of the planet’s most inhospitable environments.