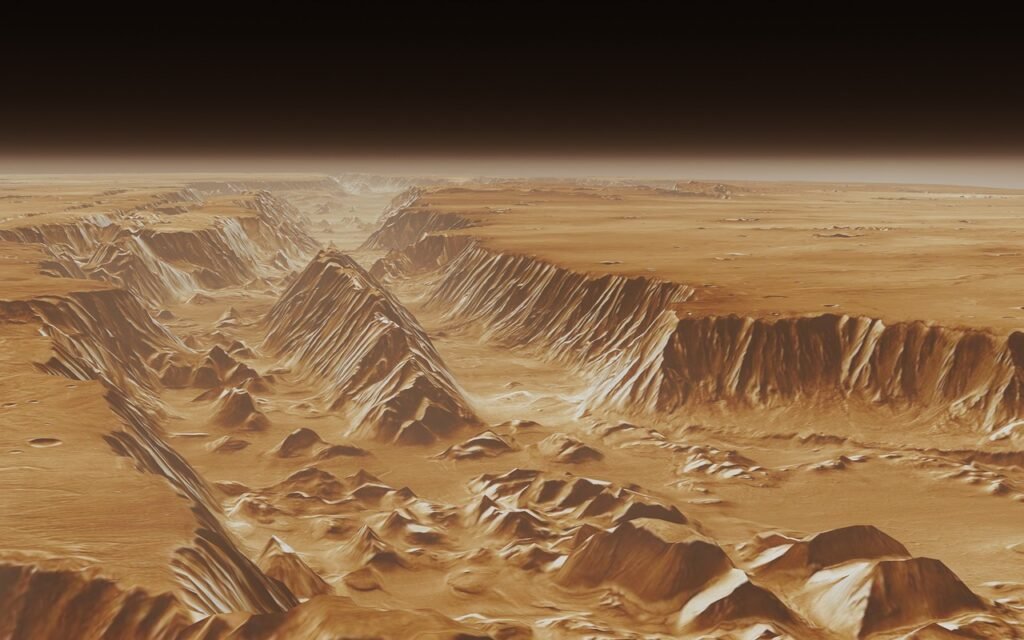

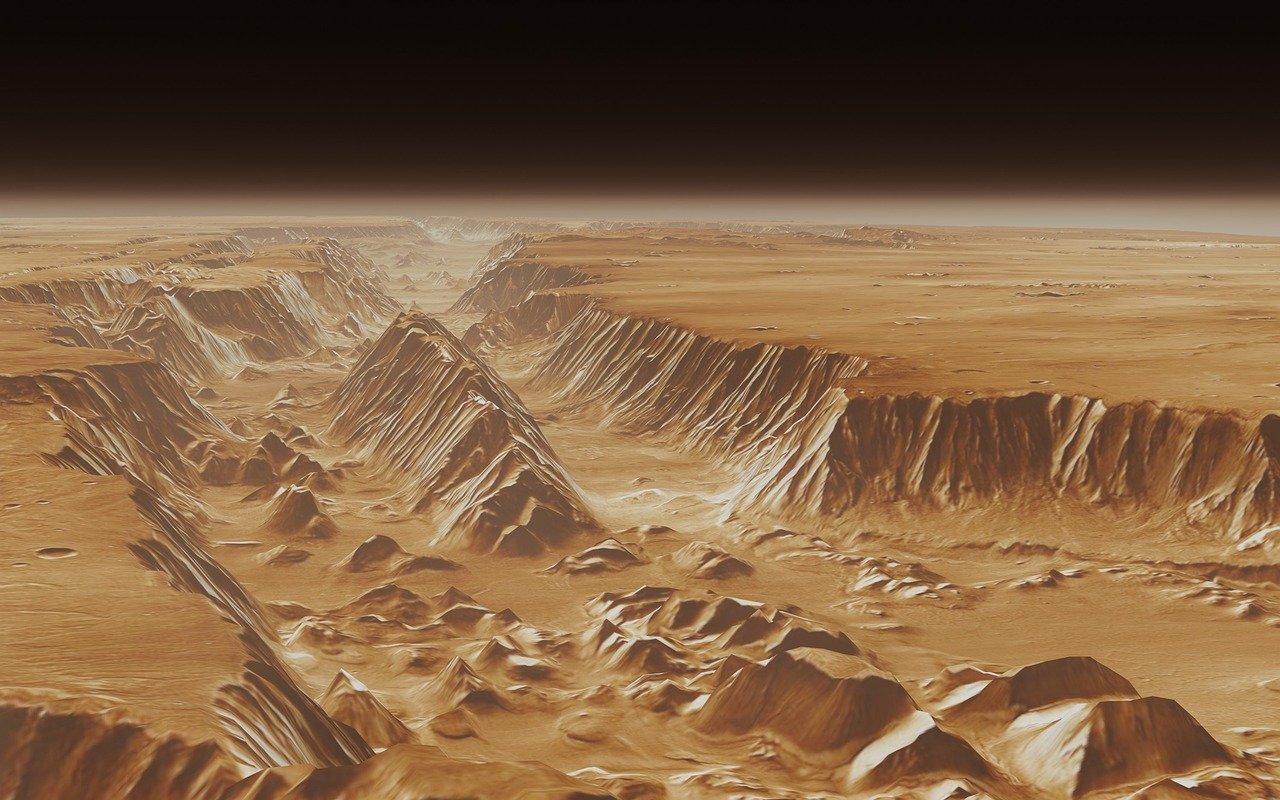

Unearthing Clues in the Canyon Depths (Image Credits: Pixabay)

Valles Marineris, Mars – River deltas nestled within the solar system’s largest canyon system have provided scientists with the clearest signs yet of a massive ancient ocean that once blanketed half of the Red Planet.

Unearthing Clues in the Canyon Depths

Stretching more than 4,000 kilometers across Mars’ equator, Valles Marineris dwarfs Earth’s Grand Canyon and now reveals geological secrets from billions of years ago.[1][2]

Researchers identified scarp-fronted deposits, or fan-shaped deltas, in the southeastern Coprates Chasma section of the canyon. These structures formed where rivers deposited sediment into standing water, marking a former shoreline at elevations between -3,750 meters and -3,650 meters.[2]

The deposits span radial distances of 2 to 2.5 kilometers, with surface slopes rising from about 10 degrees to over 27 degrees at their fronts. Upstream, deeply incised valleys funneled water from drainage basins up to 75 square kilometers in area.[2]

Deciphering the Geological Signatures

High-resolution images from orbiters like NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and ESA’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter captured these features in unprecedented detail. The deltas exhibit convex break-in-slopes, radial drainage networks, and textures such as desiccation cracks measuring 5 to 20 meters across—hallmarks of fan-deltas prograding into a sea or paleolake.[1][2]

Such formations mirror terrestrial examples, where rivers meet oceans, but Mars’ lower gravity influenced sediment deposition. The consistent shoreline elevations extend from Valles Marineris westward to chaotic terrains in the northern lowlands, suggesting a connected body of water.[2]

- Break-in-slopes at precisely -3,750 meters mark the primary paleoshoreline.

- Secondary levels at -3,650 meters indicate minor fluctuations up to 100 meters.

- 19 tributary valleys, with incision depths from tens to over 500 meters, fed the deltas.

- Dune ripples and scree overlie the structures, remnants of later arid conditions.

- Similar deposits appear in Aurorae Sinus and Hydraotes Chaos.

Voices from the Research Team

Ignatius Argadestya, a Ph.D. student at the University of Bern who led the analysis, described his discovery during mapping: “When measuring and mapping the Martian images, I was able to recognize mountains and valleys that resemble a mountainous landscape on Earth. However, I was particularly impressed by the deltas that I discovered at the edge of one of the mountains.”[1][3]

His supervisor, Professor Fritz Schlunegger, emphasized the Earth-Mars parallels: “Delta structures develop where rivers debouch into oceans, as we know from numerous examples on Earth. The structures that we were able to identify in the images are clearly the mouth of a river into an ocean.”[1]

Argadestya added a poignant reflection: “We know Mars as a dry, red planet. However, our results show that it was a blue planet in the past, similar to Earth.”[3]

Timeline and Scale of the Lost Sea

The deltas date to the boundary between the Late Hesperian and Early Amazonian epochs, around 3 billion years ago, when surface water peaked on Mars. This high-stand represented the planet’s maximum sea level, linking the canyon to northern basins.[2]

The ocean rivaled Earth’s Arctic Ocean in size, submerging roughly half of Mars’ northern hemisphere. Previous hints from shorelines, outflow channels, and rover data in places like Jezero crater and Utopia Planitia now gain robust support from these direct shoreline markers.[1]

Key Takeaways

- Clear shoreline evidence elevates confidence in a planet-spanning ocean.

- High-resolution orbital data bridges Earth geology with Martian landforms.

- Mars’ habitable window coincided with peak water availability ~3 billion years ago.

This breakthrough not only rewrites chapters of Mars’ geological story but also underscores how fleeting liquid water can be on a planet. What do you think this means for the search for past life on Mars? Tell us in the comments.