Overturning a Stubborn Assumption (Image Credits: Unsplash)

Researchers have discovered that immense pressure in the ocean depths transforms sinking organic particles into a key energy source for microbes far below the sunlit surface.[1][2]

Overturning a Stubborn Assumption

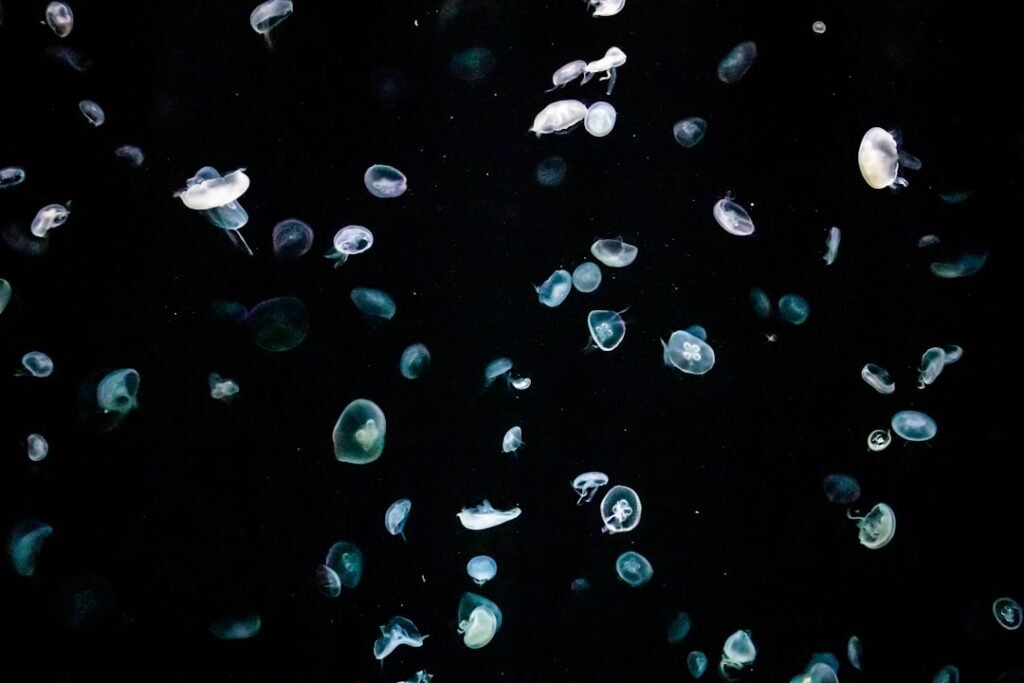

Scientists long regarded the deep ocean as a desolate food desert for water-column microbes, surviving on meager rations amid vast darkness. A recent study from the University of Southern Denmark shattered this view by revealing substantial nutrient releases from marine snow.[3] Up to half of these particles’ carbon content escaped as dissolved organics during descent, providing an overlooked subsidy that sparked rapid microbial growth.

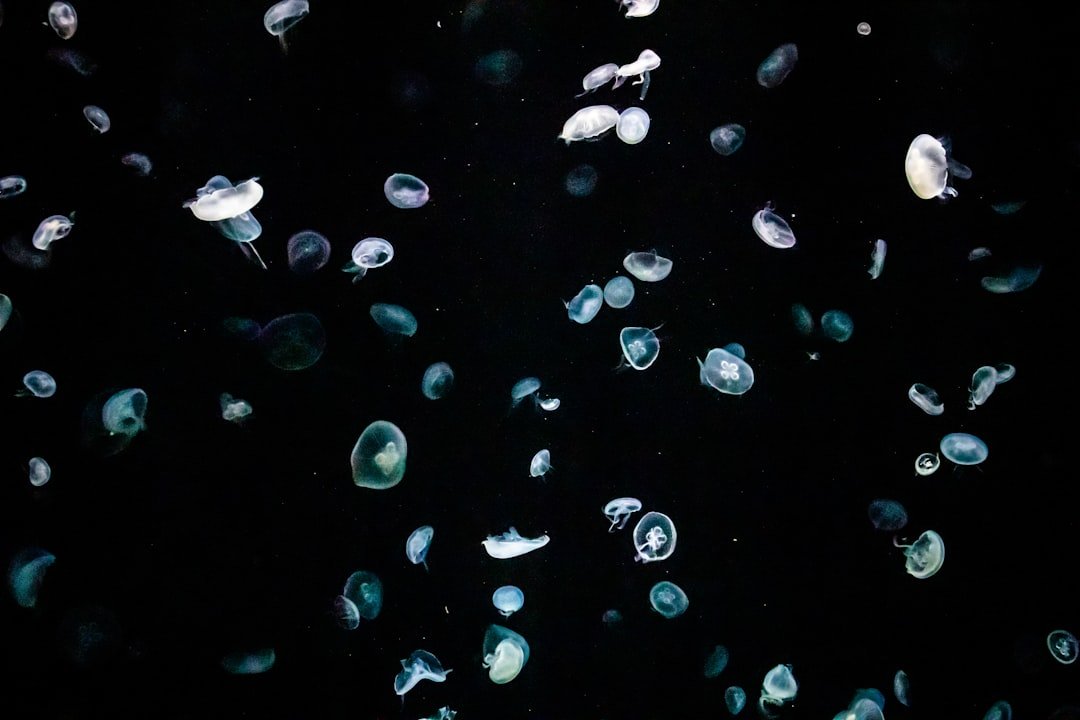

The investigation centered on diatom aggregates, common builders of marine snow. Biologists simulated deep-sea conditions in rotating pressure tanks, where particles endured forces equivalent to 2 to 6 kilometers underwater. This setup prevented settling while mimicking the relentless squeeze of hydrostatic pressure.

How Pressure Acts as a Natural Juicer

Marine snow consists of dead algae, microbes, and debris that clump in surface waters and sink steadily, resembling underwater flurries. As these particles plunged deeper in experiments, pressure triggered leakage of dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen – primarily proteins and carbohydrates.[4]

“The pressure acts almost like a giant juicer,” stated lead author Peter Stief, an associate professor at the university’s Department of Biology. “It squeezes dissolved organic compounds out of the particles, and microbes can use them immediately.”[1] Tests across multiple diatom species confirmed consistent results, with 58 to 63 percent of initial nitrogen also leaking out.

Microbes Capitalize Swiftly on the Bounty

Free-floating bacteria in the deep water column wasted no time exploiting the fresh supply. Within two days of exposure, their numbers surged thirtyfold, while respiration rates climbed sharply, signaling heightened metabolic activity.[2]

Chemical profiles of the leaked material – low carbon-to-nitrogen ratios and high protein-like fluorescence – marked it as highly bioavailable. This rapid uptake demonstrated how pressure-driven leakage sustains vibrant microbial communities in otherwise sparse environments.

- Bacterial abundance rose by a factor of 30 in 48 hours.

- Respiration rates increased markedly, confirming energy use.

- Leaked compounds included readily digestible proteins and carbohydrates.

- Effects persisted across diatom varieties tested.

Implications for the Global Carbon Cycle

The findings ripple through understandings of Earth’s carbon dynamics. Fewer organics reach seafloor sediments for long-term burial, as substantial fractions dissolve into the water column instead. There, carbon lingers for hundreds to thousands of years before resurfacing, rather than millions in sediments that once formed oil and gas reserves.

“This process affects how much carbon the ocean can store and for how long,” Stief noted. “It is relevant for understanding climate processes and for improving future models.”[3] The discovery refines estimates of the biological carbon pump’s efficiency, urging updates to climate projections.

| Depth Range | Carbon Leakage | Nitrogen Leakage |

|---|---|---|

| 2-6 km | Up to 50% | 58-63% |

Key Takeaways

- Pressure squeezes labile organics from marine snow, challenging deep-ocean nutrient scarcity.

- Microbes thrive rapidly on leaked proteins and carbs, boosting deep-sea activity.

- Less carbon buries in sediments, altering long-term ocean storage models.

This breakthrough not only illuminates hidden life in the abyss but also prompts oceanographers to revisit carbon flux assumptions, with field expeditions planned aboard the research vessel Polarstern to verify patterns in the Arctic. How might these revelations shift our grasp of planetary climate regulation? Share your thoughts in the comments.