For centuries, the violent Roman amphitheater spectacles have fascinated historians and the general public. Gladiatorial battles, beast hunts, and executions in public were a mainstay of Roman entertainment but physical records of these gruesome happenings are thin. Today, a skeleton from York, England, with unmistakable lion’s bite marks on it, presents the first tangible evidence that these brutal spectacles occurred in Roman Britain.

The skeleton, that of a man in his late 20s, tells a gruesome story: mauled by a large cat, probably in an arena, then decapitated after death. This find not only proves long-standing rumors regarding Britain’s involvement in Rome’s blood sports but also leaves shivering questions about the manner in which prisoners, gladiators, and foreign animals were killed in the empire’s most northerly province.

A Cemetery of the Damned: York’s Gladiator Burial Ground

The skeleton was found in the Driffield Terrace cemetery, just outside Roman York (Eboracum), a site long suspected to hold the remains of gladiators or executed criminals. Of the 82 burials excavated, over 70% were decapitated, many with their heads placed at their feet, a practice often linked to executions. The majority were young men, aged 18 to 45, with evidence of chronic violence: healed facial lacerations, broken knuckles, and combat injuries to the spine.

Bioarchaeological analysis revealed another anomaly: these men came from across the Roman Empire, some as far as the Middle East. Their diets were rich in grains, similar to gladiators’ known “barley-and-bean” regimen. While skeptics argue they could be soldiers or criminals, the sheer concentration of violent deaths suggests something more sinister an arena’s toll.

The Lion’s Jaw: Forensic Evidence of a Big Cat Attack

The key evidence comes from one skeleton, labeled 6DT19. His pelvis bore deep, circular puncture wounds 5 to 7 mm wide and up to 5 mm deep consistent with the bite of a large carnivore. Forensic analysis ruled out weapons, scavenging dogs, or bears. Instead, the spacing and curvature of the marks matched those of a lion or leopard.

Modern zoological studies show that big cats kill by suffocation (crushing the neck) or mauling the torso. The fact that this man’s injuries were confined to his pelvis suggests he was already downed, perhaps incapacitated in an arena before the animal struck. His decapitation, likely post-mortem, may have been a final act of ritual killing.

Beast Hunts in Britannia: Rome’s Deadliest Entertainment

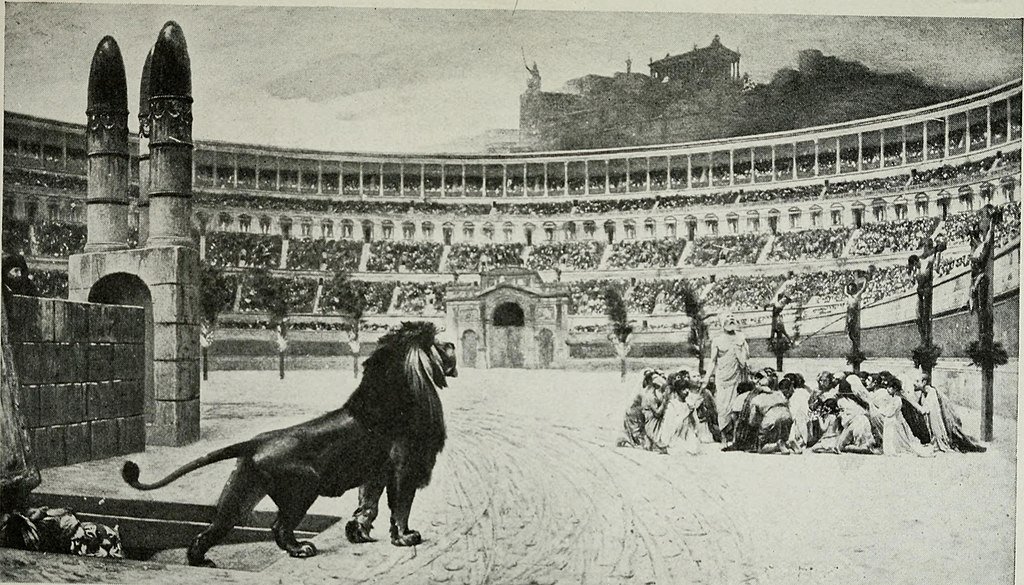

Roman arenas staged venationes (beast hunts), where armed fighters (venatores) battled lions, bears, and bulls. More gruesomely, criminals and prisoners faced damnatio ad bestias execution by animals. While mosaics and texts describe these spectacles, physical proof was absent until now.

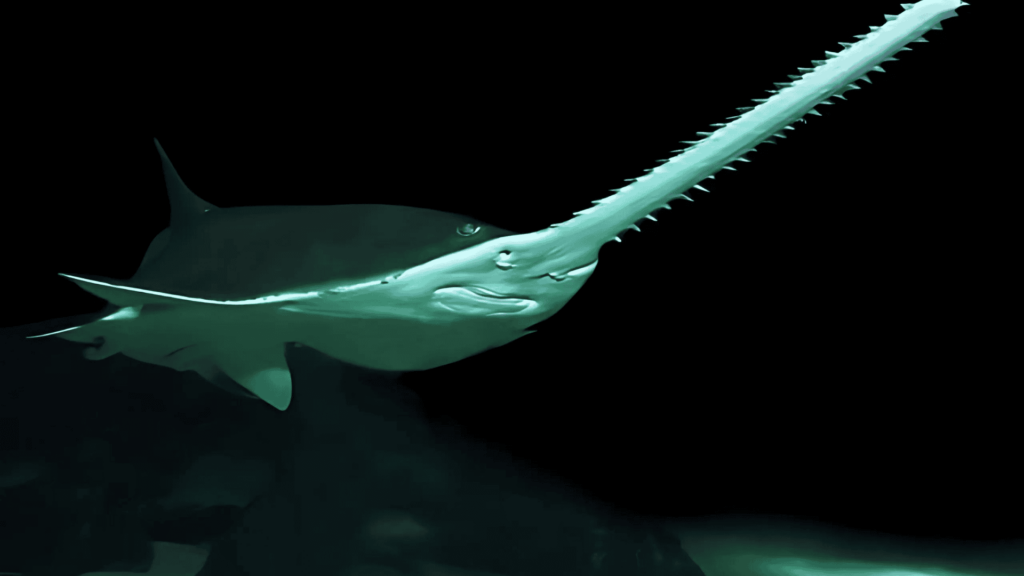

Britain had amphitheaters (like those in Chester and Caerleon), but no bones of exotic animals had been found. This skeleton changes that. The lion that attacked 6DT19 was likely imported from North Africa, a logistical feat requiring specialized handlers and transport.

A North African Connection: How Lions Reached York

The fact that a lion existed in Roman Britain poses an urgent question: How did it arrive?

Historical records suggest York had strong ties to North Africa, especially under Emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211 AD), who was born in Libya. His reign saw an influx of African goods and possibly animals into Britain. A mosaic at Rudston Villa depicts a lion named Leo Flammefer (“Fiery Lion”), hinting at local beast shows.

Shipping lions had taken wooden boxes, ships, and trained staff arduous trips where some animals perished. That at least one such reached York speaks volumes about the empire’s large trade networks as well as the elite’s frenzy for exotic attractions.

Executed or Entertained? The Man Behind the Bite Marks

Who was 6DT19? A condemned criminal? A gladiator? A prisoner of war?

His wounds indicate repeated violence, appropriate to a gladiator’s existence. However, his decapitation corresponds to executions. Roman law sentenced damnatio ad bestias for deserters, rebels, and Christians. In case he was a captured foe (maybe Scottish or German), his death would have served as a public warning.

Alternatively, he could have been a venator, a beast hunter who lost his final fight. Either way, his skeleton is a rare, visceral link to Rome’s darkest entertainments.

The Legacy of Rome’s Bloody Spectacles

This find reconsiders our definition of Roman Britain as brutal. Although gladiator fighting was an open secret, the deployment of foreign large cat beasts proves definitely that Britain’s elites produced Rome’s same splendiferous and deadly presentations.

It also highlights the globalized cruelty of the empire: lions dragged from Africa, men from across Europe, all dying for distant spectators’ amusement. For 6DT19, death came by tooth and blade, a fate immortalized not in art, but in bone.

Final Thoughts: A Window into Ancient Violence

The York lion-bitten skeleton is more than a curiosity it’s a direct witness to Roman savagery. In an era where most evidence comes from poems or mosaics, these bones tell an unfiltered story of pain, spectacle, and empire.

As archaeologists refine their methods, who knows what other horrors lie buried? For now, 6DT19 stands as a grim testament: in Rome’s Britain, death was not just punishment it was entertainment.

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.