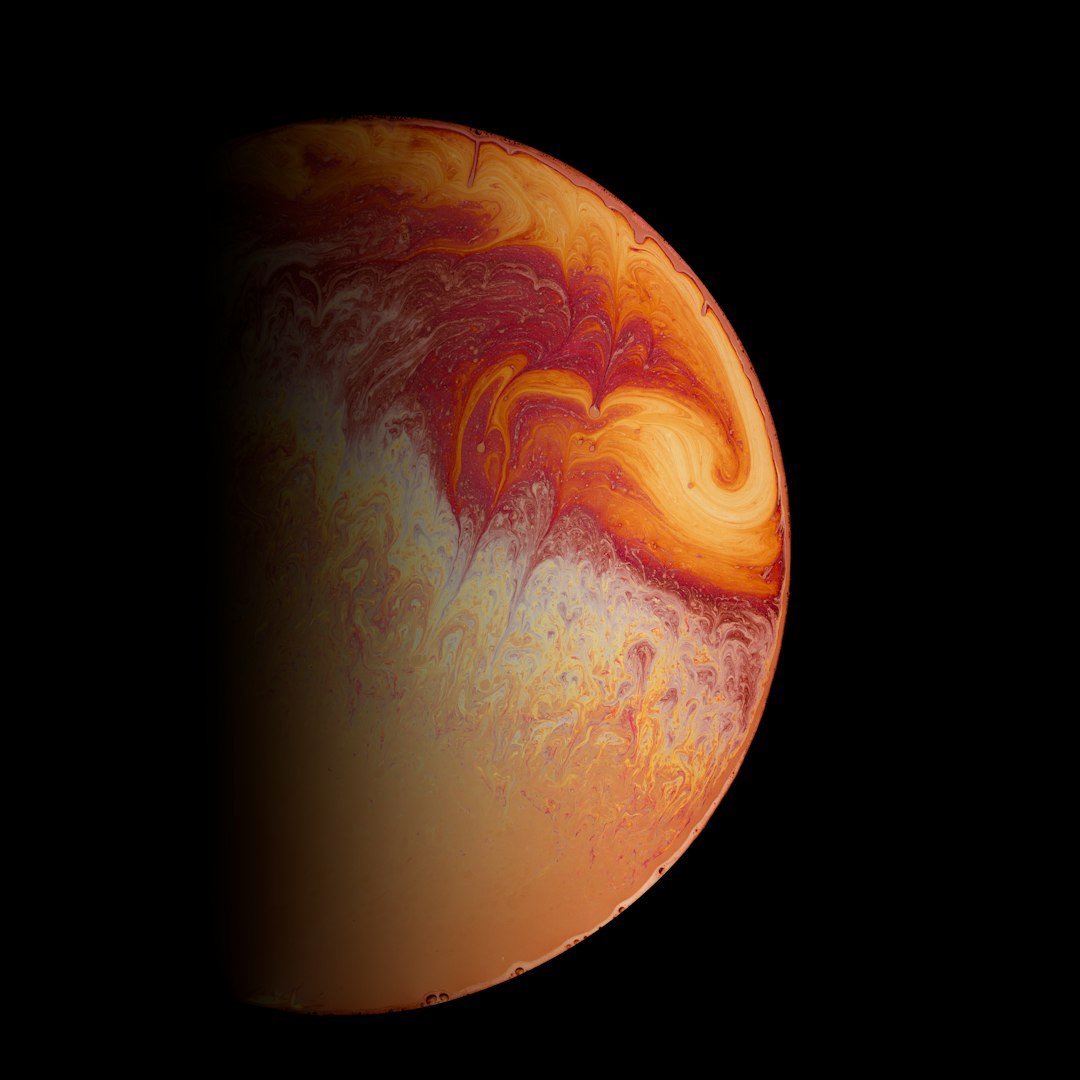

Picture a sky so bright it glows pearly white, a planet where the air itself is heavy and hot, and droplets of acid drift like endless mist. Venus has tempted explorers and dreamers for generations, and the latest wave of studies is reviving an unusually human question: what would it feel like to move through those clouds? The mystery is thorny because Venus gives with one hand and takes with the other – there’s a “Goldilocks” slice of atmosphere with friendlier pressure and temperature, yet it’s soaked in sulfuric acid and whipped by roaring winds. Engineers sketch floating cities while chemists argue over what’s really in the haze, and somewhere between them is a simple, visceral test: could a person ever swim there? I once tried to imagine it during a late-night notebook session, and the math was as humbling as the sky is gorgeous.

The Hidden Clues

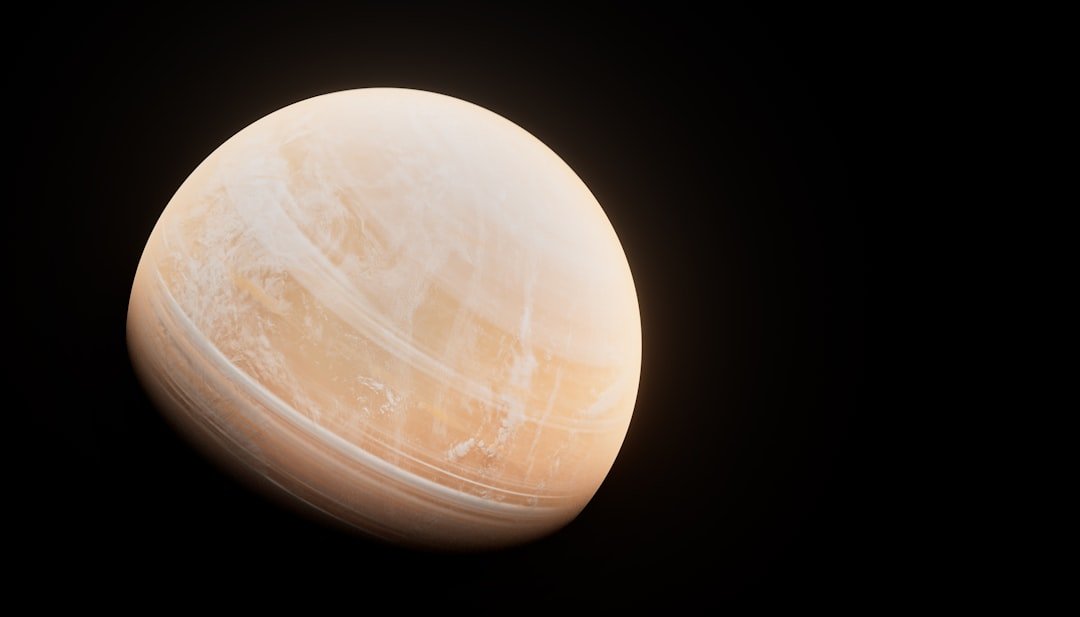

Start where the evidence is strongest: around fifty to sixty kilometers above the Venusian surface, the pressure sits roughly in the same ballpark as sea level on Earth and the air can warm to the kind of heat you’d find in a sauna. That’s the sweet band that keeps popping up in mission proposals and science fiction sketches alike. But comfort ends quickly, because these clouds are not cotton candy; they are concentrated sulfuric acid droplets suspended in a carbon-dioxide heavy atmosphere.

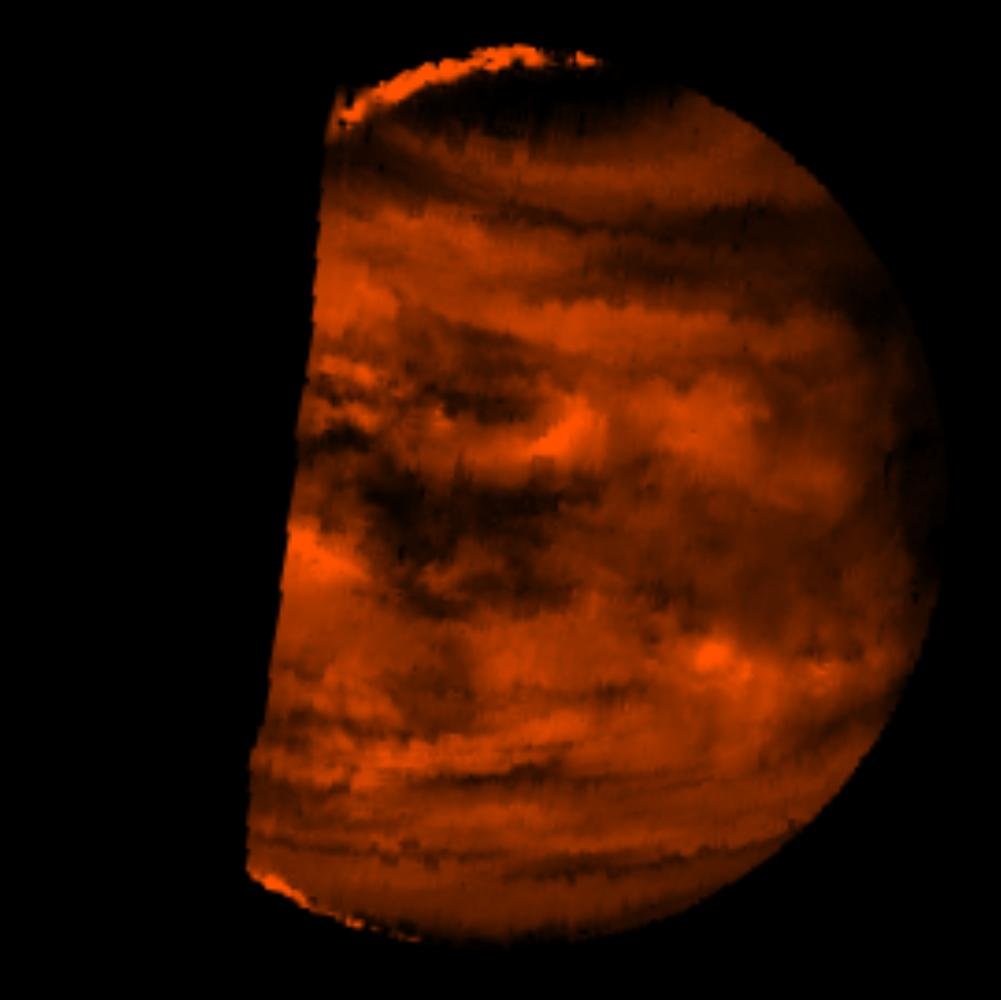

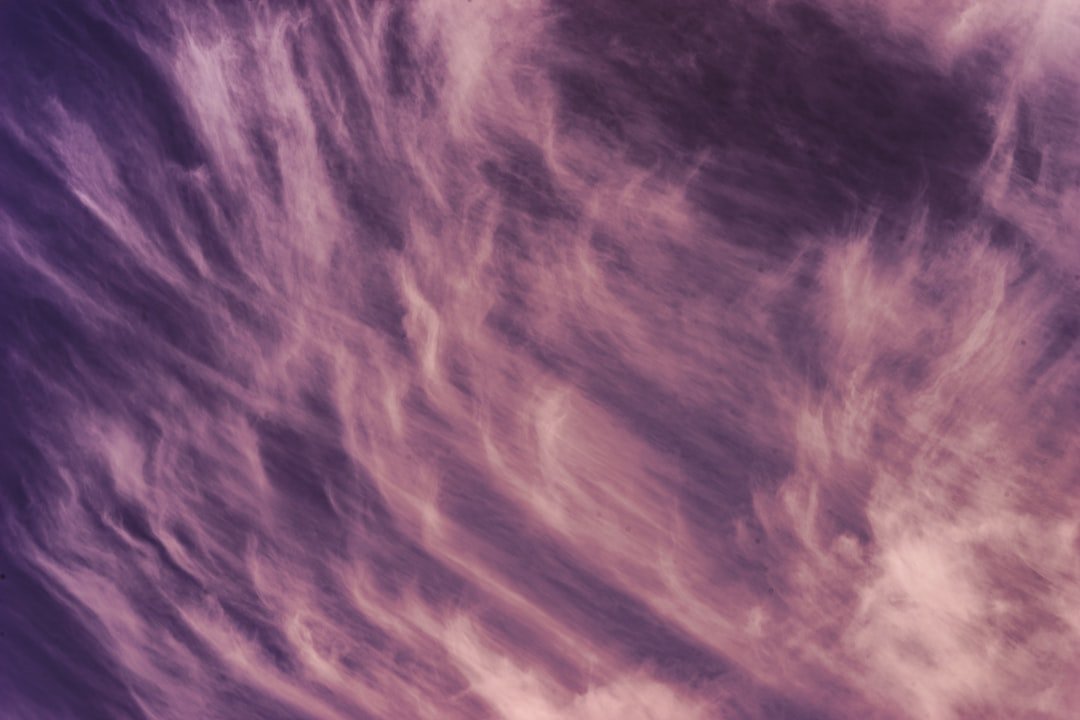

Spacecraft past and present have probed this realm and keep finding a layered, restless system rather than a soft blanket. Winds race around the planet in a global superrotation, pushing cloud decks faster than Venus itself spins. If you want to “feel” Venus, the first clue is that everything up there moves fast and bites hard.

Anatomy of a Venusian Cloud

Venus’s clouds are an aerosol: microscopic acid droplets drifting in gas, not a continuous liquid mass. In a rainstorm on Earth you still swim in water because the medium is liquid; in Venus’s cloud deck you’d be moving through gas sprinkled with droplets. The droplets are real enough to corrode metals and haze a visor, but they don’t give you the solid, pushable resistance that water does.

Temperature and pressure shift with altitude, shaping three main layers and hazes above and below. The middle region is where conditions look temptingly Earth-like on paper, yet the chemistry remains alien. Imagine trying to backstroke through a mist of battery acid while the room fans are set to hurricane.

Could a Human Float, Fly, or Swim?

Here’s the heart of it: “swimming” means using your body to push against a fluid dense enough to give you purchase. In liquid water, that works beautifully; in air, even on dense Venus, your strokes hardly bite. Without wings or a balloon, you’d simply fall, though the thicker atmosphere would slow your descent more than on Earth.

Oddly, there’s a loophole that engineers love. A human-safe mix of nitrogen and oxygen is lighter than Venus’s carbon dioxide, so a sufficiently large suit or habitat filled with breathable air could float like a blimp. In other words, you can’t really swim in the clouds, but you might float in them – and once floating, you could “swim” metaphorically by paddling inside a craft, the way a child moves around a pool noodle.

The Acid Test: Materials and Survival

Venus’s cloud droplets are strong sulfuric acid, the kind that shrugs at most plastics and gnaws at metals. Any suit or vehicle would need outer skins of fluoropolymers – think tough, slick materials in the Teflon family – backed by corrosion-resistant composites. Even then, seals, joints, and sensors must be shielded or constantly rinsed by onboard systems.

Breathing is its own challenge because the ambient gas lacks oxygen and is loaded with carbon dioxide and sulfur compounds. Ventilation and filtration would work overtime, and any exposure would be a race between chemistry and engineering. This isn’t scuba diving; it’s more like strolling through a laboratory spill while the lab tries to blow you sideways.

From Ancient Visions to Modern Science

For centuries, Venus was the morning star, a mirror to myth rather than a place with weather. That romance cracked open when Soviet Venera landers sent back data from the hellish surface and orbiters later mapped the planet’s skin beneath the cloud veil. The picture that emerged is stranger than any legend: a scorched ground under a crushing sky and, far above, a temperate band of acid mist.

As instruments sharpened, scientists chased faint chemical hints in the clouds, including debated signs that stirred big questions about atmospheric chemistry and even habitability. The debate itself has been useful, forcing better calibrations and new observing strategies. Science moved Venus from poetry to paperwork, and yet the allure never left.

Why It Matters

The practical payoff is not a novelty swim but a new kind of laboratory for climate and chemistry. Venus shows what happens when a greenhouse effect runs to extremes, offering a cautionary bookend to Earth’s atmosphere. Studying its clouds teaches us how aerosols form, grow, and interact with radiation – skills that matter for understanding pollution and climate feedbacks at home.

Compared with traditional planetary targets like Mars, Venus pushes materials science harder and demands new mobility concepts. Instead of rovers rolling on rocks, think balloons surfing wind streams and probes sipping droplets mid-flight. Each problem we solve there, from acid-proof coatings to autonomous flight in chaotic winds, loops back into industries on Earth.

The Hidden Clues, Revisited: Winds, Drag, and Human Motion

Let’s circle back to the motion question with a physicist’s lens. Drag in gas scales with density and speed, so Venus’s thicker air gives you more “grip” than Earth’s, but it’s nowhere near the firm resistance of water. A freestyle stroke that propels you a meter in a pool would barely nudge you in the clouds.

Now add superrotating winds that can scream around the globe faster than the planet turns. Any human-scale movement would be swallowed by that flow without a stabilizing envelope or wings. If you want to move with purpose, you’re designing a vehicle, not a workout routine.

Human Factors: Heat, Vision, and Sense of Place

Beyond chemistry, living perception would be odd in those clouds. Light is bright but scattered, turning the world into a diffuse white room where shadows smear and horizons fade. Pilots and divers train for spatial disorientation; Venus would make that disorientation the default.

Thermal control has to dump heat efficiently in a hot, thick atmosphere that resists radiating energy away. Cooling loops would hum constantly, and every watt of power would be a careful trade. Under that load, small comforts – clear visors, stable footing, a reliable horizon – become survival tools.

Conclusion

Big leaps start small. If Venus intrigues you, follow the mission roadmaps, support student balloon projects, and nudge local schools or makerspaces to build acid-proof materials demos. Citizen-science groups that analyze telescope data often need volunteers, and public comment periods for space agency budgets make a difference.

Closer to home, track research on aerosols, corrosion-resistant coatings, and autonomous flight in turbulent air – breakthroughs there echo across medicine, energy, and climate tech. Curiosity is the fuel here, and you don’t need a rocket to carry it. So, if not swimming, what kind of motion would you design for a human to dance with Venus’s clouds – glider, balloon, or something no one’s named yet?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.