In a move that sounds equal parts science fiction and ecological moonshot, Colossal Biosciences says it’s turning its de-extinction toolkit toward New Zealand’s vanished giant, the moa. The announcement arrives with cinematic flair, including backing from filmmaker Sir Peter Jackson and collaboration with Māori partners and museum scientists who hold some of the world’s best-preserved moa remains. What’s at stake is more than spectacle: it’s a test of whether modern genomics, avian reproductive biology, and cultural governance can work in sync. Supporters frame the effort as ecological repair and scientific progress; skeptics call it a seductive detour that risks overpromising. The next few years will show whether this giant of the past can become a proof of concept for the future – or a cautionary tale.

The Hidden Clues

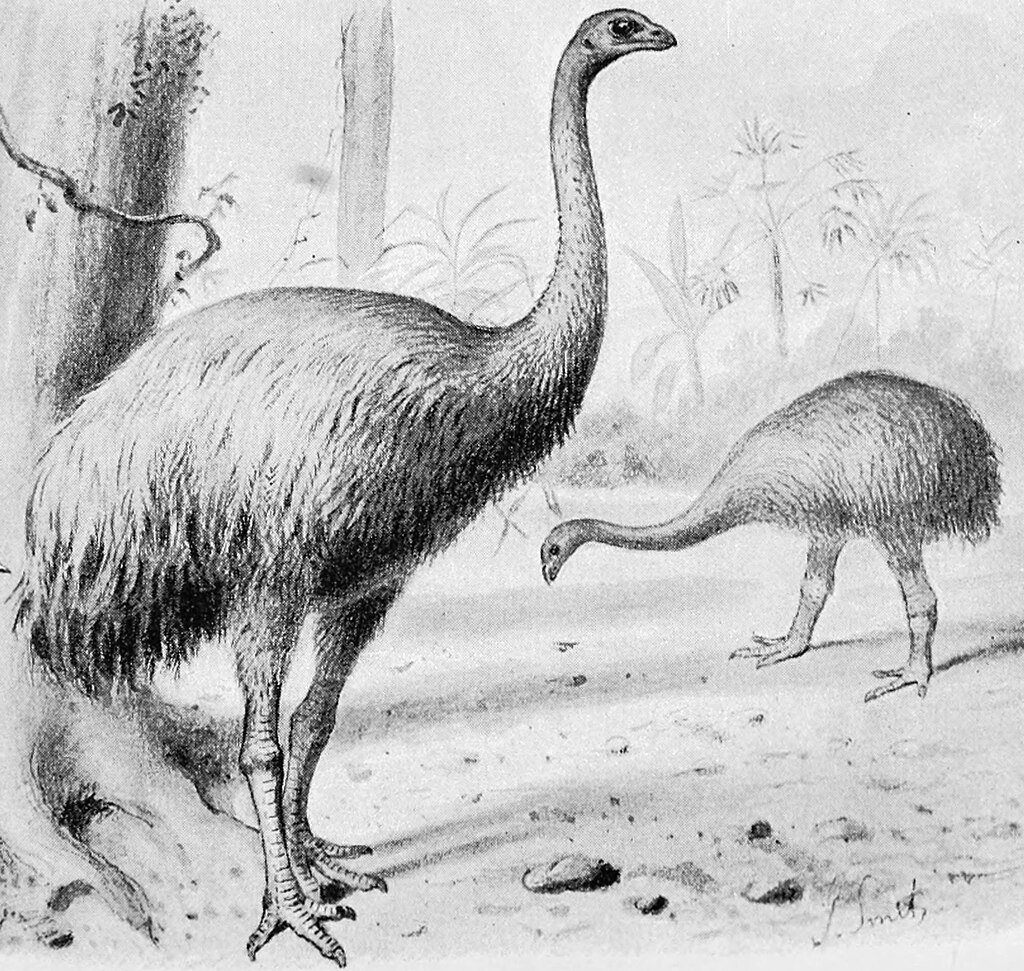

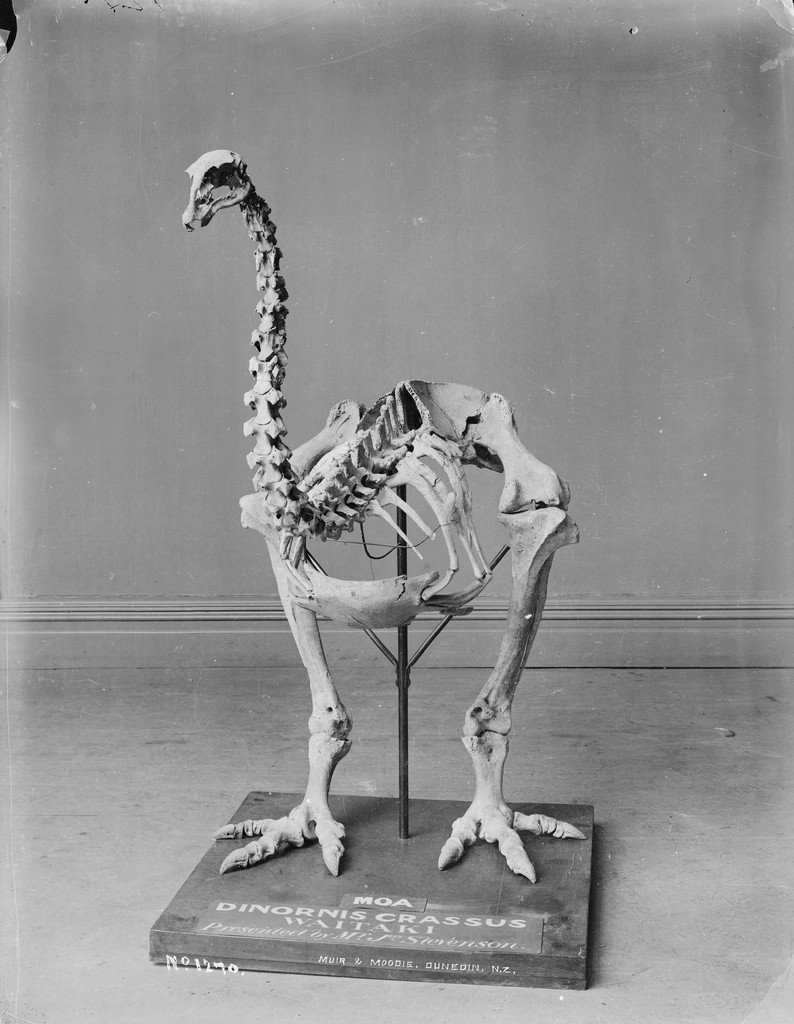

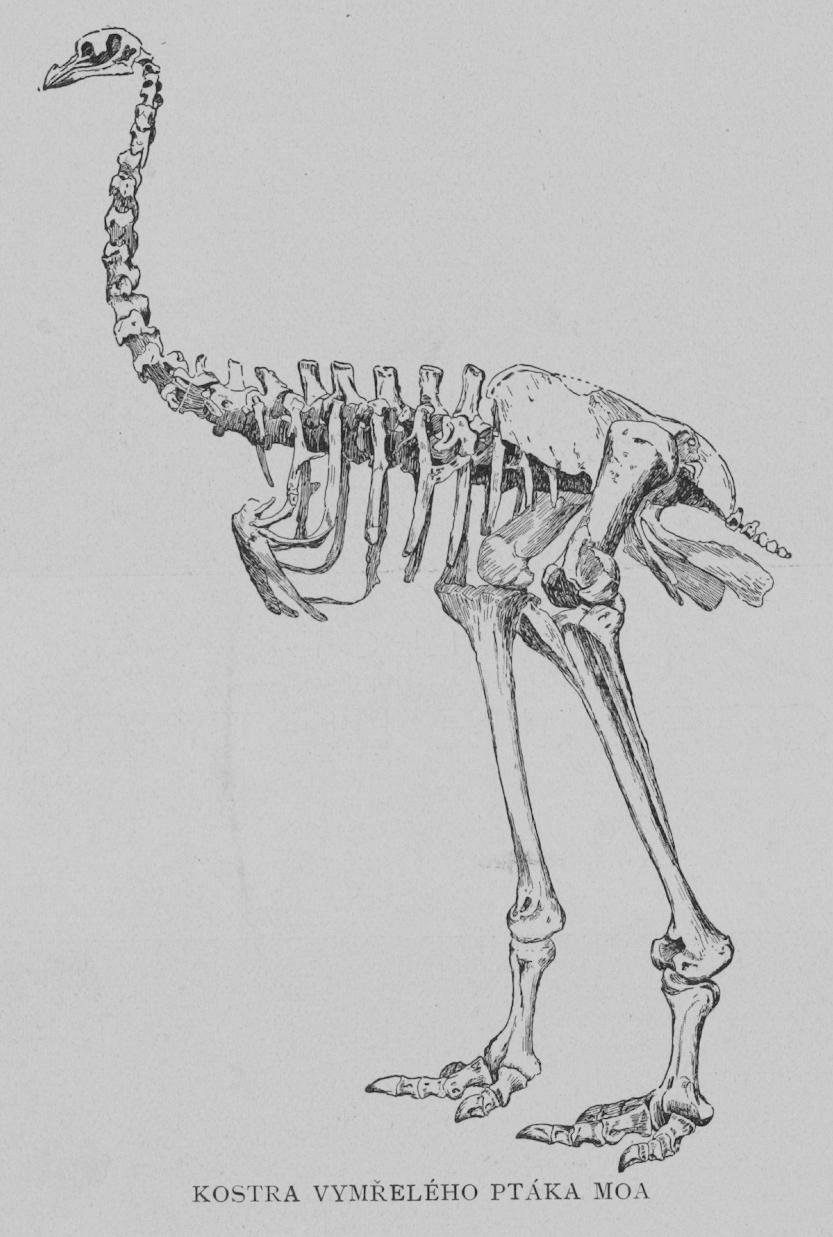

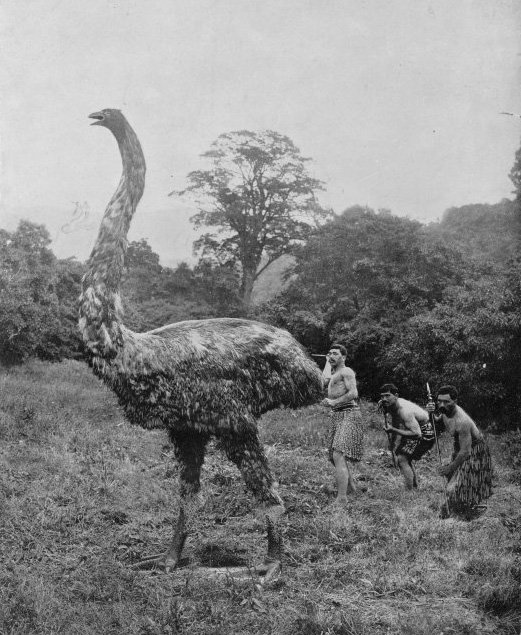

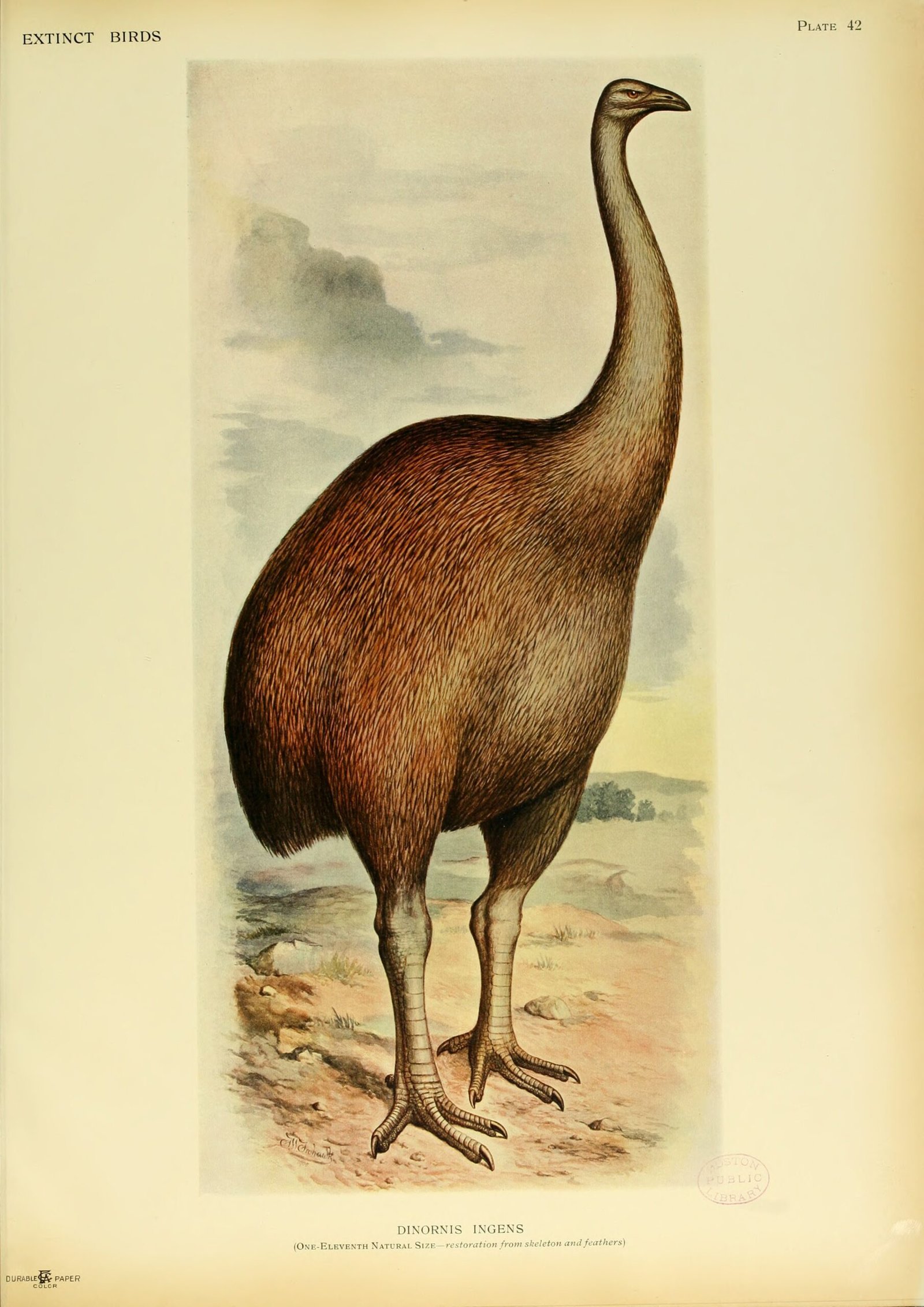

Start with bones – vaults of them – because the moa’s story still lives in calcium and collagen. Canterbury Museum’s collections, alongside other archives and iwi-held taonga, form the physical archive for ancient DNA that scientists hope to piece into a workable genome. The moa weren’t just big; the South Island giant moa could stand roughly up to three and a half meters when stretching its neck, a detail that turns dry numbers into a visceral sense of scale. These remains are the breadcrumb trail through time, letting researchers compare fragments across individuals and species to spot conserved sequences and evolutionary divergences. The promise here is practical: cleaner reference genomes mean fewer guesswork edits later in the lab. The risks are equally concrete – ancient DNA is damaged, patchy, and biased toward what happened to survive, not necessarily what matters most biologically. ([1news.co.nz](https://www.1news.co.nz/2025/07/09/sir-peter-jackson-backs-project-to-de-extinct-moa-experts-cast-doubt/?utm_source=openai))

From Ancient Bones to Modern Genomes

Turning relics into roadmaps requires sequencing countless short DNA shards, then stitching them against genomes of living relatives like emus or tinamous to reconstruct moa chromosomes. Colossal and collaborators describe an approach that pairs biobanking with high-coverage sequencing and algorithmic assembly, all aimed at surfacing the genes that shape body plan, growth, immunity, and metabolism. The company frames this as incremental – first a draft, then iterative refinements toward a functional reference suited for editing. Archaeological context matters too, because species boundaries blur across nine moa lineages, forcing choices about which genetic “north star” to follow. Each choice is scientific and cultural: which moa, for which ecosystem, under whose authority. It’s meticulous, unglamorous work that sets the ceiling for everything that follows in the lab. ([colossal.com](https://colossal.com/moa/?utm_source=openai))

Inside the Lab: How a Moa Could Be Built

Birds pose a special engineering puzzle because standard mammal cloning doesn’t translate neatly to eggs, so teams lean on primordial germ cell transfer and genome editing in a surrogate species. In practice, that means editing cells from a close relative – likely an emu – so they carry engineered moa-like germ cells, then breeding birds that pass those edits to offspring. The first passes target large-effect genes tied to morphology – height, feathering, beak shape – because those are easiest to spot and edit, but survival traits like fertility or disease resistance are complex, polygenic, and stubborn. Conservation geneticists warn that focusing on “headline genes” can leave fragile animals that look the part yet struggle to thrive. Scaling from one edited bird to a self-sustaining population multiplies the challenge, because small founder groups shed diversity quickly. In short, the lab can start a story; evolution, husbandry, and time have to finish it. ([sciencemediacentre.co.nz](https://www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz/2025/07/09/moa-de-extinction-plans-announced-expert-reaction/?utm_source=openai))

The Cultural Compass

In Aotearoa New Zealand, science does not – and should not – move without cultural license, so project leaders emphasize partnerships with Māori, including Ngāi Tahu, and plans for iwi-led stewardship. That matters because moa were once woven into food webs, stories, and landscapes that carry living obligations, not just historical curiosity. Advocates say a Māori-governed reserve could define respectful care and data sovereignty from the start, rather than bolting ethics onto a finished product. Others urge patience and broader consultation, noting that different iwi have different relationships to moa and to de-extinction itself. The distinction between a true moa and a moa-like engineered bird also cuts to the heart of cultural authenticity and whether a created animal can ever be considered taonga in the same way. The social license question, in other words, is as pivotal as the genome. ([rnz.co.nz](https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/566386/sir-peter-jackson-backs-project-to-bring-back-extinct-moa?utm_source=openai))

Why It Matters

De-extinction is more than a headline; it’s a stress test of conservation priorities in a century of shrinking habitats and accelerating loss. Traditional conservation protects what’s left and restores what can be saved; de-extinction proposes a third track – engineering ecological function where species have vanished. If it works, the tools could backstop endangered birds by repairing harmful variants, boosting disease defenses, or even restoring lost behaviors through assisted selection. If it stumbles, scarce money and attention could drift from immediate needs like predator control, biosecurity, and habitat recovery that demonstrably raise survival odds today. The moa project, then, becomes a barometer of whether cutting-edge genetics can complement, not cannibalize, frontline conservation. For readers used to seeing conservation as triage, this is a reframing with real stakes. ([sciencemediacentre.co.nz](https://www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz/2025/07/09/moa-de-extinction-plans-announced-expert-reaction/?utm_source=openai))

Ecological Stakes in Aotearoa and Beyond

Before humans arrived, moa were the dominant large browsers, shaping forests, dispersing big seeds, and indirectly supporting apex predators like Haast’s eagle. Losing them re-tuned the entire system, with some plants evolving alongside a partner that suddenly disappeared, and seed shadows shrinking without a giant herbivore to carry them. A moa-like browser could, in theory, re-open those closed loops by moving seeds farther and pruning vegetation in ways small birds and introduced mammals don’t replicate. Yet ecosystems aren’t static museum dioramas; modern New Zealand has new predators, new pathogens, and altered climates that could trip up any rewilding attempt. That’s why the most credible roadmaps talk about staged releases and fenced reserves that learn by doing rather than assuming instant harmony. Ecological replacement is possible, but it’s not a rewind button. ([colossal.com](https://colossal.com/moa/?utm_source=openai))

Signals From the Past Year

The moa announcement lands in the shadow of a controversy: earlier this year Colossal touted a dire wolf milestone, then later clarified the animals were gene-edited gray wolves rather than resurrected dire wolves. Critics see a pattern of overreach; the company calls it transparent iteration toward ecological stand-ins that matter functionally more than taxonomically. For the moa, that distinction may be decisive – will success be defined by DNA percentages, by phenotype, or by what the birds actually do in a forest? New Zealand scientists have urged caution on timelines suggesting hatchlings within a decade, arguing that engineering, husbandry, and population management are likely to take longer. Public trust hinges on calibrating excitement with constraints, not just in press releases but in published data and external oversight. The next updates will need to speak in papers, not just promises. ([rnz.co.nz](https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/566386/sir-peter-jackson-backs-project-to-bring-back-extinct-moa?utm_source=openai), [sciencemediacentre.co.nz](https://www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz/2025/07/09/moa-de-extinction-plans-announced-expert-reaction/?utm_source=openai))

The Future Landscape

Technically, the frontier looks like this: higher-fidelity genome assemblies, safer multiplex editing, better avian germline chimeras, and scalable incubation that respects welfare. Logistically, it calls for biosecure facilities, long-term funding, veterinary depth, and adaptive management plans that can pivot as animals teach researchers what works and what fails. Socially, the path runs through co-governance agreements that define data rights, benefit sharing, and the conditions for any step toward open landscapes. Globally, success could set templates for other lost herbivores that structured ecosystems at scale; failure could harden skepticism and narrow funding for genomic conservation more broadly. Either way, the project will reverberate well beyond New Zealand’s shores, shaping norms for how biotech and biodiversity intersect. The most realistic expectation might be staged, carefully monitored outcomes – not instant giants roaming the bush. ([colossal.com](https://colossal.com/moa/?utm_source=openai), [sciencemediacentre.co.nz](https://www.sciencemediacentre.co.nz/2025/07/09/moa-de-extinction-plans-announced-expert-reaction/?utm_source=openai))

What You Can Do

Stay curious but demand clarity: look for peer-reviewed results, welfare protocols, and independent oversight rather than buzz alone. Support conservation groups in Aotearoa and wherever you live that protect habitat, block invasive predators, and stabilize endangered bird populations now. If you’re in education or policy, consider how genomic tools might complement – not replace – proven conservation, and push for frameworks that center indigenous governance where species and cultures intertwine. Engage respectfully with Māori perspectives on taonga, whakapapa, and kaitiakitanga, understanding that consensus isn’t automatic or uniform. And if you choose to donate, split support between tangible on-the-ground work and the research that could make future interventions safer and more equitable. The healthier today’s ecosystems are, the better any tomorrow’s innovations will fare.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.