A quiet dig in Romania unearthed more than ancient bones it cracked open our understanding of when and how humans first stepped into Europe. What seemed like a routine fossil find turned out to be a game-changer in the timeline of human migration.

A Quiet Discovery That Shook the Timeline of Human Expansion

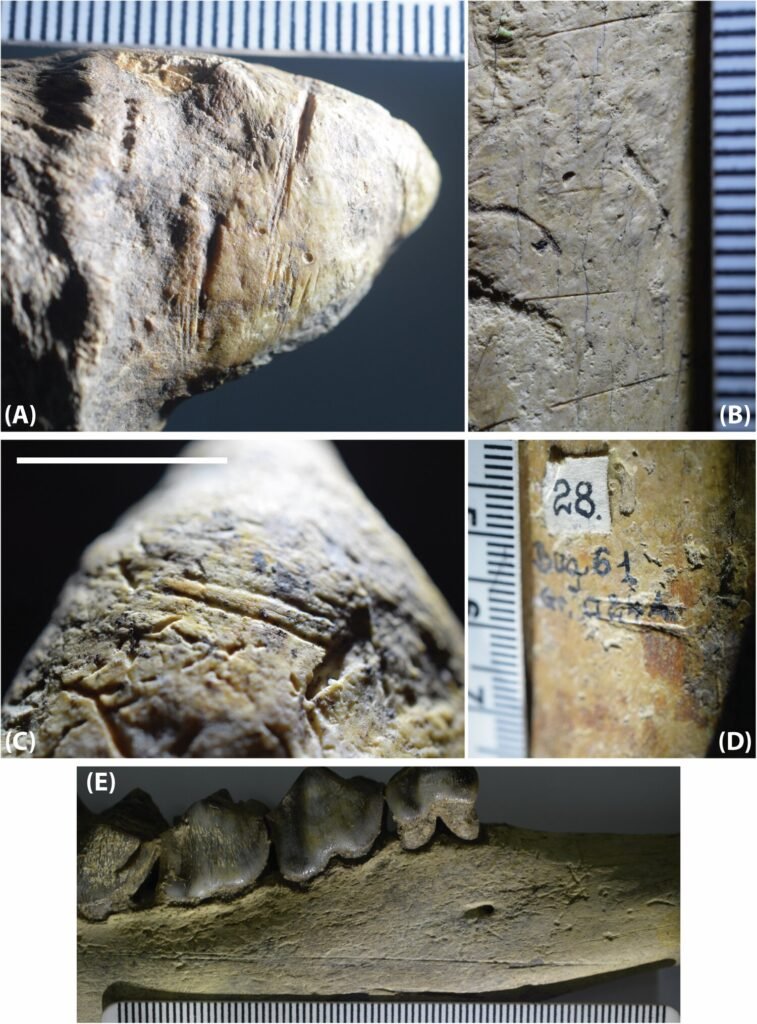

In 2017, while peering through a magnifying lens at what appeared to be a simple animal fossil from Romania, paleoanthropologist Sabrina Curran paused. Illuminated by a low-angled light, several fine V-shaped lines emerged marks unmistakably carved by stone tools nearly 2 million years ago. That moment of stillness gave birth to a seismic shift in our understanding of early human migration.

What Curran discovered were cut marks on fossilized animal bones at the Grăunceanu site marks that predate all previously confirmed human activity in Eurasia. This revelation, coupled with discoveries at Dmanisi in Georgia, doesn’t just challenge the long-standing timelines of human dispersal; it fractures them.

Cut Marks That Cut Through Assumptions

Grăunceanu, an open-air fossil site nestled in southern Romania, had been largely overlooked since its excavation in the 1960s. Researchers knew it held a trove of well-preserved animal fossils, but the lack of original records had dimmed its scientific relevance until now.

Over 4,500 bones were painstakingly reexamined by a team including Curran, Claire Terhune, Samantha Gogol, and Chris Robinson. They were searching for one thing: traces of early hominin behavior. And they found them. Specifically, 20 bones bore unmistakable tool-inflicted incisions, with eight considered high-confidence cut marks often located precisely where muscle would be stripped from bone.

In isolation, that might not sound revolutionary. But the bones were dated using uranium lead analysis to 1.95 million years ago, pushing the known presence of human ancestors in Europe back by at least 150,000 years.

Grăunceanu: A Prehistoric European Serengeti

Picture this: a gently meandering river cuts through a patchwork of forest and open grasslands. Herds of giraffes graze under the watchful eye of saber-toothed cats. Pangolins, ostriches, hyenas all animals we associate with Africa roamed freely in what is now modern-day Romania.

This wasn’t just a hunting ground; it was a crossroads of ancient ecosystems. And within this wild mélange, a small group of hominins butchered deer, carved meat from bones, and perhaps unbeknownst to them etched themselves into the very fabric of human history.

The “bone nest,” as Grăunceanu’s fossil concentration was once called, is more than a catchy moniker. It hints at something remarkable: a preservation so intact that the spatial arrangement of bones mimicked how they fell in life and death. That level of detail offers rare ecological insights and now, cultural ones.

The Georgian Connection: Dmanisi and the Trail of Stone Tools

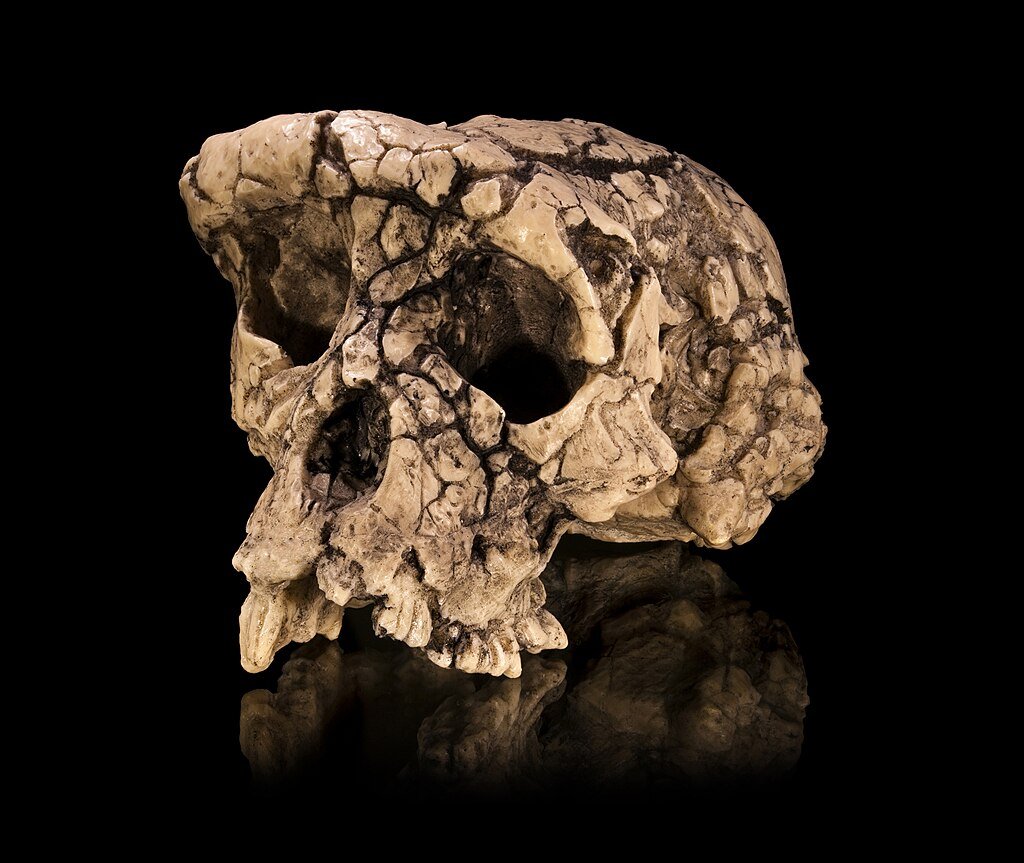

To understand the implications of Grăunceanu, we must look east 1,500 kilometers away to the Dmanisi site in Georgia. Until recently, Dmanisi was considered the earliest confirmed evidence of hominins in Eurasia, dated between 1.85–1.78 million years ago. There, archaeologists uncovered not only butchered bones but five skulls of Homo erectus with startlingly small brains and surprisingly primitive physiques.

The Dmanisi hominins challenged the notion that bigger brains and sophisticated tools were prerequisites for migration. These early humans, armed only with basic Mode I technology (think sharp flakes, not hand axes), managed to adapt and thrive in temperate Eurasia long before they were thought capable.

Now, Grăunceanu adds weight to the idea that this wasn’t an isolated leap, but part of a broader, earlier wave of expansion. Together, the sites form a continental corridor of migration that could reshape the very narrative of human prehistory.

From Africa to Eurasia: A More Complex Departure

For decades, the textbook version of human migration started with Homo erectus leaving Africa around 1.8 million years ago presumably equipped with evolving brains, growing bodies, and sharper tools. But if Grăunceanu’s dating is accurate, then our ancestors were already experimenting with Eurasian frontiers before some of those evolutionary “milestones” occurred.

In fact, some Dmanisi fossils are dated earlier than their African counterparts. That means the African “launchpad” theory may need revision. Perhaps early hominins didn’t so much explode into Eurasia as they trickled outward testing new territories while still evolving.

What’s more, these pioneers weren’t necessarily advanced. With cranial capacities barely above modern chimpanzees and stone flakes as their only tools, they were resourceful, not revolutionary. And yet, they spread across continents.

Microscopes, Molds, and the Case for Certainty

Skeptics often question whether markings on ancient bones are really from tools or merely natural abrasions scratches from river movement, predator bites, or trampling. To tackle this, zooarchaeologists Michael Pante and Trevor Keevil deployed a cutting-edge 3D optical profiler.

By comparing the microscopic shape of the Grăunceanu marks with a database of 898 known traces from lion bites to sediment scrapes they built an airtight case. The result? A suite of quantitative evidence supporting what Curran saw with her trained eye: the unmistakable handiwork of ancient butchers.

This fusion of qualitative and quantitative analysis represents a new gold standard in archaeological verification. It’s not just what you see it’s how deeply you can measure and compare it.

Rethinking the Map of Human Origins

The implications of Grăunceanu and Dmanisi go far beyond Romania and Georgia. They invite a fundamental reassessment of human migration narratives. Was Eurasia not a destination but an experimental ground for early Homo? Did small-brained hominins with primitive tools venture farther, earlier, and more frequently than we’ve ever dared to believe?

What’s clear is that Eurasia was likely occupied before Homo erectus made its debut in the East African fossil record. That’s not just academic trivia it means Europe and Asia played a more active role in shaping our lineage from the very beginning.

Grăunceanu may lack hominin fossils, but it tells a vivid, tangible story. One of deer hunted along an ancient riverbank. Of hands wielding crude stone tools with surprising efficiency. Of a continent echoing with footsteps we’re only now beginning to hear.

A Window into a Forgotten World

The power of a scratch on bone may seem insignificant even. But in the right context, under the right light, those scratches become sentences in a long-forgotten book.

The discoveries at Grăunceanu and Dmanisi don’t just fill gaps in the fossil record. They have forced us to rewrite entire chapters of human history. And, perhaps more profoundly, they remind us that our species’ journey has always been about curiosity, courage, and an unwavering desire to progress long before we became fully human.

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.