Imagine a world frozen in time, where an entire forest stands eerily silent under a blanket of ash, every leaf and insect perfectly preserved as if waiting for a story to be told. Volcanic eruptions, often associated with chaos and destruction, can also act as nature’s most meticulous archivists. While their power can reshape continents and end civilizations, it’s the gentle, silent work that happens after the eruption—the slow burial of life under layers of volcanic debris—that gives us an astonishing window into the distant past. Let’s journey into the heart of these natural time capsules and discover how, beneath the ash, lost ecosystems whisper their secrets to anyone willing to listen.

The Explosive Power of Volcanoes

When a volcano erupts, it unleashes forces that are both awe-inspiring and terrifying. Hot magma, once trapped beneath the Earth’s crust, bursts forth as lava, ash, and gases. This explosive event can obliterate everything in its path within minutes. Trees, animals, and even entire landscapes can vanish under a tide of molten rock and swirling, choking ash. Yet, as shocking as this destruction may be, the aftermath sets the stage for something extraordinary. The rapid burial caused by these eruptions is what allows ecosystems to be preserved in remarkable detail, almost like pressing pause on the chaos of life.

A Blanket of Ash: Nature’s Time Capsule

Volcanic ash acts like a protective shroud, falling thick and fast over anything in its way. Unlike slow, gradual burial by sediment, ash can entomb plants and animals so quickly that even delicate features—the veins on a leaf, the fur on a mouse—might survive. This sudden encapsulation halts decay and shields organic remains from scavengers and weather. Over centuries, the ash hardens into rock, sealing away a snapshot of life before disaster struck. These natural vaults can remain hidden for thousands of years, waiting patiently for curious scientists to uncover their secrets.

The Mystery of the Pompeii Worms

One of the most fascinating discoveries beneath volcanic ash comes from the deep sea, where volcanic eruptions fuel entire ecosystems. Near hydrothermal vents, scientists found Pompeii worms—tiny creatures that thrive in scalding water thanks to the minerals spewed by underwater eruptions. When these vents erupt and are buried by ash, they can preserve not just the worms themselves but the entire micro-ecosystem around them. Studying these preserved systems gives us insight into the resilience of life and how it adapts to the harshest conditions imaginable.

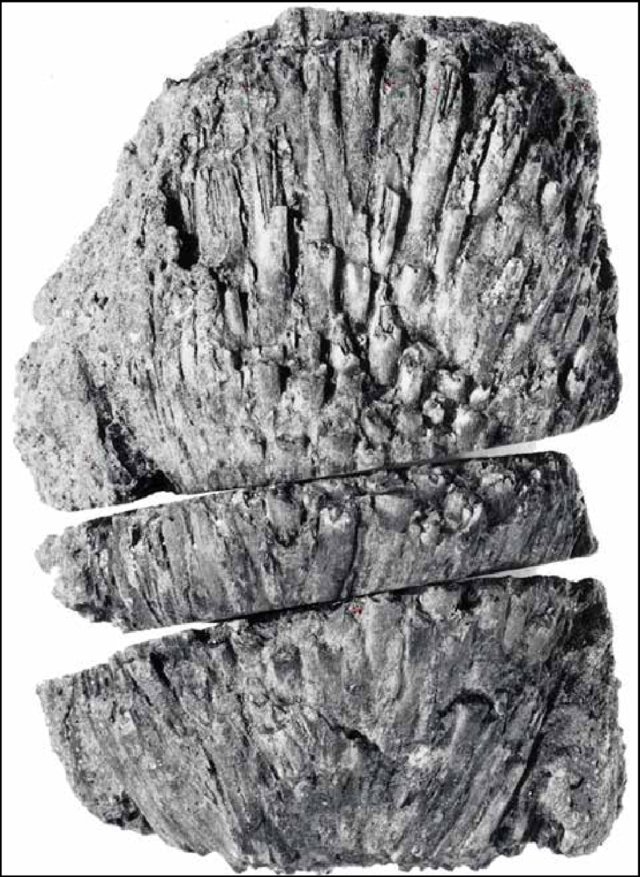

Fossilized Forests: The Story of Yellowstone

Yellowstone National Park hides one of Earth’s most spectacular examples of a fossilized forest. Millions of years ago, volcanic ash repeatedly swept across the landscape, burying entire forests layer by layer. Over time, minerals from the ash seeped into the wood, turning trees into stone. Today, visitors can walk among these petrified giants, each trunk a silent testament to a world long vanished. The detail in these fossilized trees is so precise that you can see the rings, just as you would in living wood, offering clues about ancient climates and the life that once flourished there.

Mount Vesuvius: Preserving Pompeii’s Daily Life

Perhaps the most famous example of volcanic preservation is the ancient city of Pompeii. When Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD, it buried the bustling Roman town under meters of ash and pumice. Homes, shops, artwork, and even people were frozen in their final moments. The ash preserved everything from loaves of bread in ovens to intricate wall paintings. Today, walking through Pompeii feels like stepping back in time, a vivid reminder of how sudden devastation can become an accidental gift to future generations.

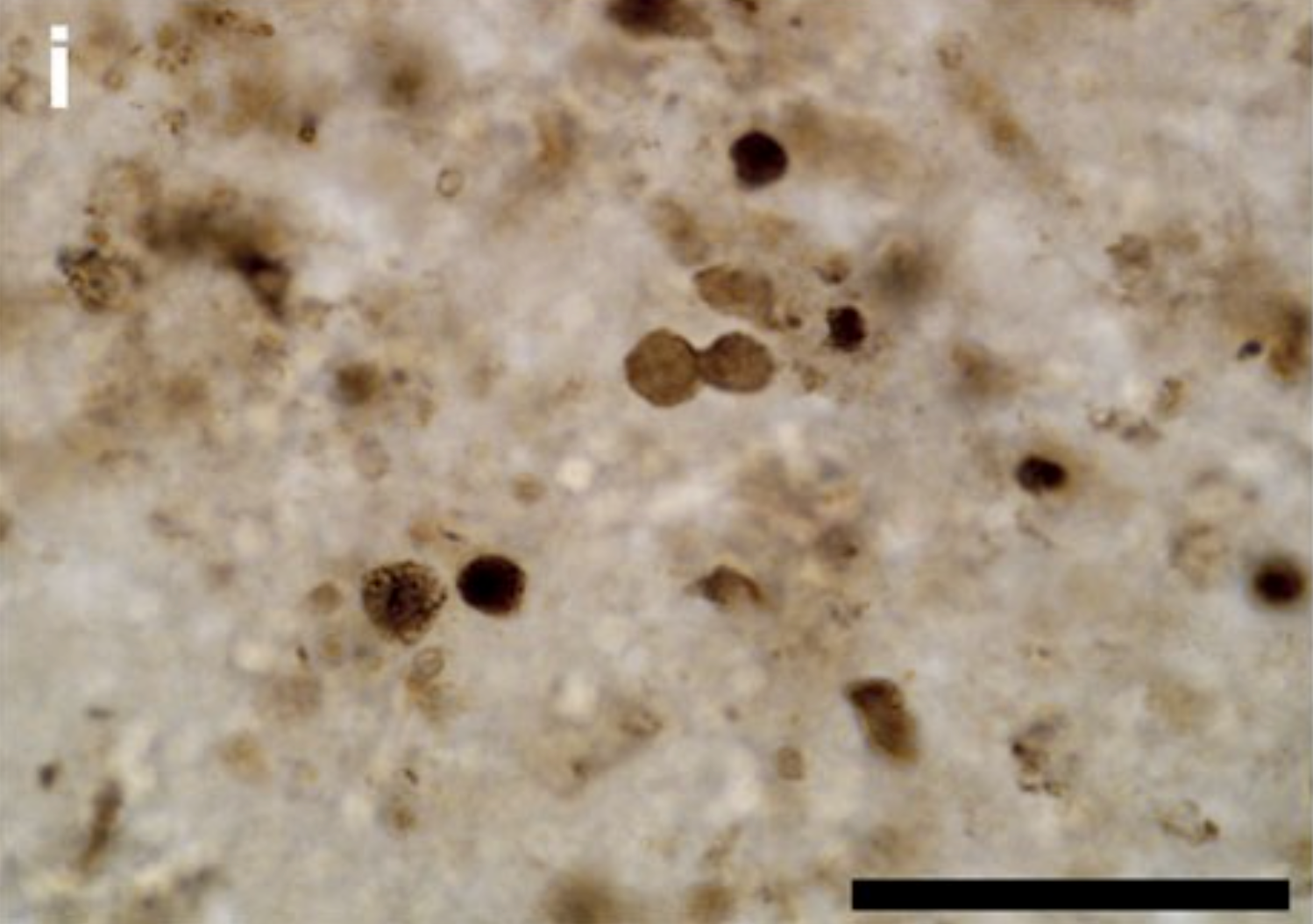

Microscopic Marvels: Preserving Pollen and Spores

It’s not just big things that get caught in the ash. Volcanic eruptions have a knack for preserving the tiniest traces of life—pollen grains, spores, and even microscopic algae. These fragments are like nature’s own data loggers, recording what kinds of plants were growing before the eruption. By studying layers of ash and the microfossils within, scientists can reconstruct ancient landscapes, track changing climates, and even learn about prehistoric diets. It’s a bit like reading an ancient diary, written in code and waiting to be deciphered.

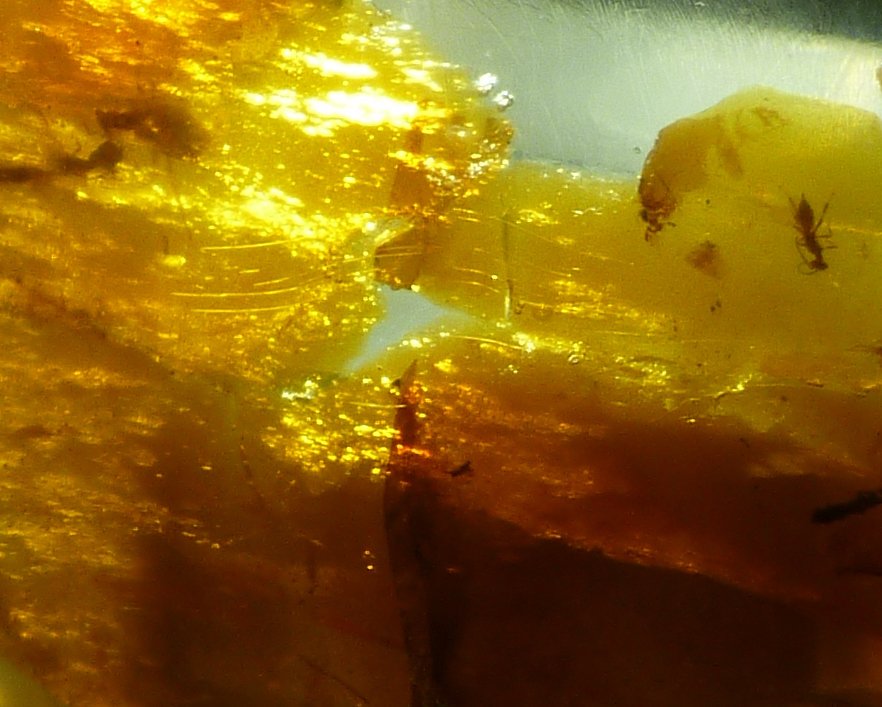

Insects in Amber: The Ash Connection

Sometimes, volcanic eruptions play a surprise role in the creation of amber, that golden fossilized tree resin famous for preserving insects. When trees are damaged by falling ash or lava, they produce more resin as a defense. This resin can trap insects, seeds, and plant fragments, and if buried quickly by volcanic deposits, it hardens into amber. These tiny time capsules provide an intimate look at prehistoric ecosystems, sometimes even preserving soft tissues, colors, and the smallest details of ancient life.

The La Brea Tar Pits: An Unexpected Volcanic Link

Though famous for their sticky tar and Ice Age fossils, the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles owe some of their preservation power to ancient volcanic activity. Volcanic eruptions helped create the conditions that allowed oil to seep to the surface and form the tar pits. Over thousands of years, animals and plants became trapped and were preserved in remarkable detail. From saber-toothed cats to mammoths, these fossils tell a dramatic story of survival and extinction, all linked to the region’s volcanic past.

Volcanoes and Ancient Human Habitats

Volcanic eruptions have preserved not just natural ecosystems but also traces of ancient human life. In East Africa, ash layers have encased footprints, tools, and even entire settlements. The famous Laetoli footprints in Tanzania, for example, were made by early humans walking across wet volcanic ash nearly four million years ago. Today, these tracks are among the oldest direct evidence of human ancestors walking upright. The ash didn’t just preserve the footprints; it immortalized a moment of family life, forever imprinted on the earth.

Volcanic Glass: Trapping the Past

When lava cools rapidly, it forms volcanic glass, known as obsidian. This glass can trap air bubbles, plant fragments, and even tiny animals. Over time, these inclusions become invaluable records of ancient environments. Archaeologists and geologists study obsidian to learn about volcanic eruptions, migration paths, and the materials ancient people used for tools. Each piece of obsidian is like a small black mirror reflecting the hidden stories of the past.

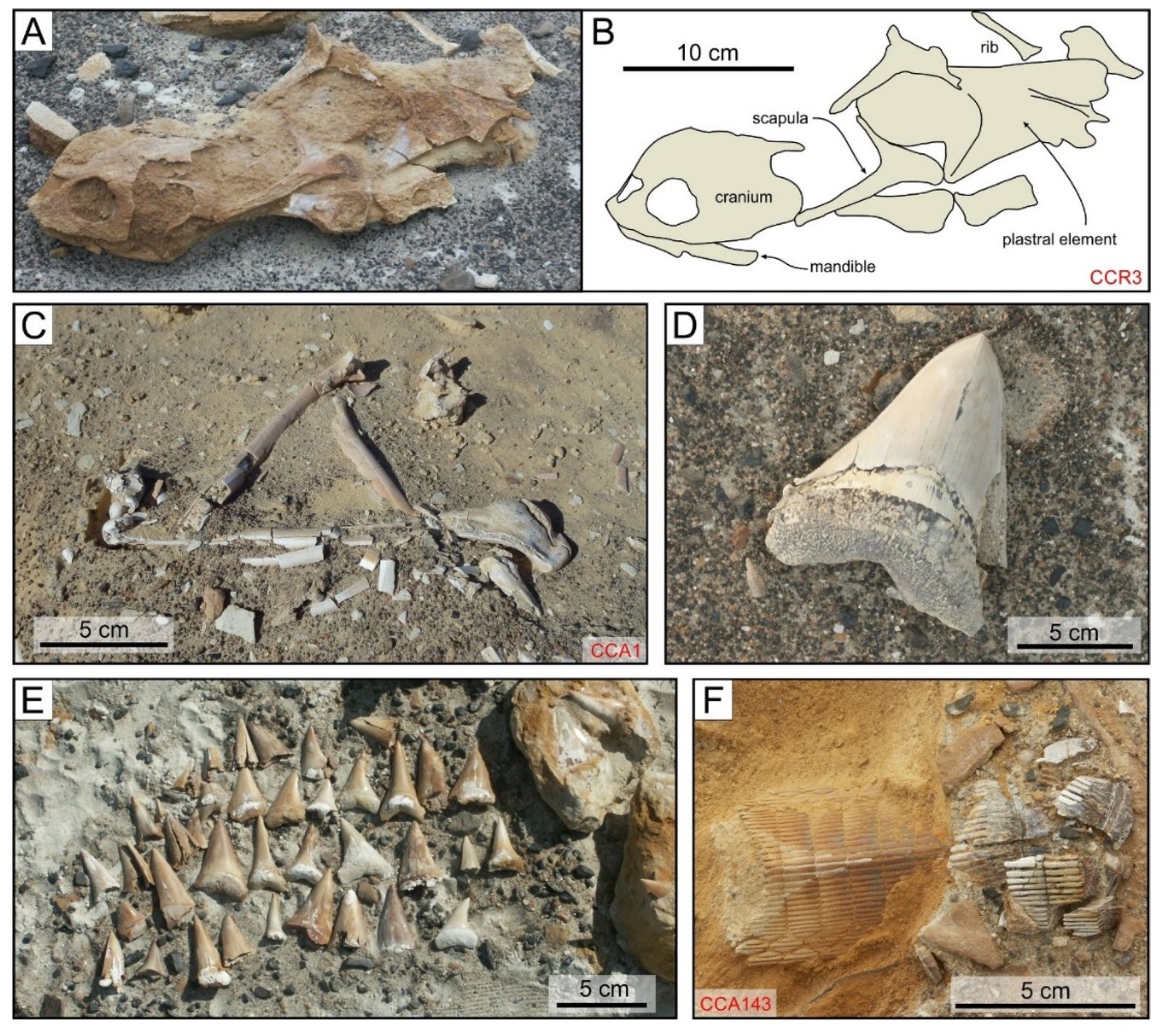

Layers of Time: How Ash Tells a Story

Each layer of volcanic ash represents a distinct moment in Earth’s history. By studying the sequence of ash deposits, scientists can build a detailed timeline of past events. Some layers are rich in fossils, while others are completely barren, marking moments of catastrophe or recovery. These layers act like the pages in a book, each one telling a different part of the story of life, death, and renewal. It’s a slow-motion drama played out over millennia, with ash as both destroyer and protector.

Resurrecting Lost Ecosystems

The preservation power of volcanic ash has allowed scientists to reconstruct entire ecosystems from the past. By piecing together fossilized plants, animals, and even microorganisms, researchers can paint vivid pictures of ancient forests, swamps, or grasslands. These reconstructions help us understand how ecosystems respond to sudden change—sometimes bouncing back quickly, other times altered forever. It’s a reminder that nature is both fragile and incredibly resilient, always finding ways to adapt and survive.

Lessons from the Past: Climate Change and Adaptation

Studying preserved ecosystems beneath volcanic ash isn’t just about curiosity—it has real-world importance today. By analyzing past eruptions and their ecological impacts, scientists gain insight into how life responds to rapid environmental change. This knowledge is especially relevant as we face modern challenges like climate change and habitat loss. The ancient records hidden beneath the ash can guide us, offering warnings and inspiration for how we might protect today’s ecosystems from tomorrow’s disasters.

Uncovering Ancient DNA

Volcanic ash can sometimes preserve genetic material—DNA—from plants and animals long since vanished. This breakthrough allows scientists to study the genetic diversity of ancient populations, trace evolutionary changes, and even understand extinct species’ relationships to those still alive today. Each tiny fragment of DNA is a message from the past, unlocking mysteries about adaptation, survival, and the web of life on Earth.

The Surprise of Soft Tissue Fossils

One of the rarest and most exciting finds in ash-preserved sites is the discovery of soft tissues—skin, muscles, or even organs. Unlike bones, which fossilize easily, soft tissues usually decay quickly. But rapid burial in fine volcanic ash can create perfect conditions for their preservation. These discoveries are like winning the scientific lottery, offering unprecedented details about ancient life—how dinosaurs looked, what plants they ate, or even what diseases they suffered.

Modern Eruptions: New Opportunities for Study

Recent volcanic eruptions, like those at Mount St. Helens and Eyjafjallajökull, have given scientists a front-row seat to the preservation process. By studying freshly buried landscapes, researchers can observe in real time how ecosystems are entombed and how recovery begins. These modern events are living laboratories, helping refine our understanding of the past and prepare for future eruptions. They’re also stark reminders of nature’s unpredictability and the delicate balance between destruction and preservation.

Volcanoes as Drivers of Evolution

While volcanic eruptions can wipe out entire ecosystems, they also create opportunities for new life to emerge. The barren landscapes left behind become blank canvases for evolution. Pioneer species—plants and animals that are the first to colonize the ash—set the stage for new communities. Over time, these areas can become hotspots of diversity, with unique species evolving to thrive in challenging conditions. Volcanoes, then, are not just destructive forces but engines of creativity and change.

Ethical Dilemmas: Excavating the Past

Unearthing preserved ecosystems beneath volcanic ash raises important ethical questions. How much should we disturb these ancient sites in the name of science? What responsibilities do we have to protect them for future generations? These dilemmas challenge scientists to balance curiosity with respect, ensuring that the treasures beneath the ash are studied thoughtfully and preserved for all.

Volcanoes in Myth and Memory

Throughout history, volcanic eruptions have left deep marks on human culture and imagination. Myths and legends often speak of gods or monsters buried beneath mountains of ash. The awe and fear these eruptions inspire are matched only by the wonder of what they leave behind—hidden worlds locked away, waiting to be rediscovered. The stories we tell about volcanoes reflect our fascination with both destruction and the hope of uncovering lost worlds.

The Future: What Lies Beneath the Next Eruption?

Every volcanic eruption has the potential to become a new time capsule, preserving a record of today’s world for the distant future. As technology advances, so too does our ability to explore these hidden archives. Who knows what discoveries still lie buried beneath the ash—forgotten forests, unknown species, or even clues to our own origins? The next great find may be just a shovel’s turn away, waiting for someone curious enough to dig.

Preserved beneath layers of ash, the lost worlds of the past are never truly gone. They wait in silence, offering lessons, warnings, and wonders to those who seek them. What stories will we uncover next?

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.