Floating on the ancient waters of Lake Xochimilco, something extraordinary was happening six centuries ago. While European farmers struggled with depleted soils and unpredictable harvests, the Aztecs had perfected a farming system so advanced that modern scientists are only now beginning to understand its brilliance. These weren’t just gardens—they were living ecosystems where soil microbes worked in harmony with human ingenuity to create what may have been the world’s most productive agricultural system.

The Living Islands That Defied Nature

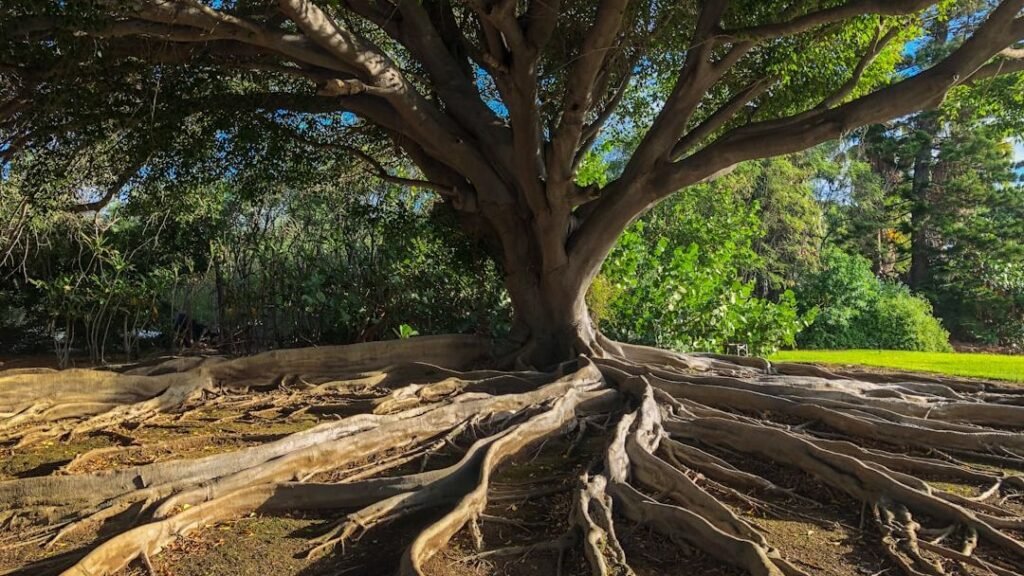

Picture artificial islands floating on freshwater lakes, where vegetables grew year-round in perfect harmony with their watery environment. The chinampas weren’t just simple rafts, though Spanish conquistadors initially mistook them for such. These were sophisticated raised field systems constructed of stacked alternating layers of mud and decaying vegetation, built with a series of long alternating strips of canals and raised fields. Each plot measured roughly 30 meters long by 2.5 meters wide, creating a checkerboard pattern across the lake surface. The stakes used for construction eventually became trees whose roots firmly held the soil of the chinampa while providing shade for the vegetables. What made these islands truly remarkable wasn’t just their construction—it was what was happening beneath the surface at the microscopic level.

A Underground City of Microbes

Recent research by Embarcadero-Jiménez and associates investigated the relationship between soil bacterial diversity and environmental factors, finding that cultivated soils have higher levels of bacterial diversity than non-cultivated soils. This discovery turned conventional thinking upside down. Most agricultural systems see declining microbial diversity over time, but chinampas seemed to nurture an increasingly complex underground ecosystem. The organization of bacterial communities showed that chinampas constitute a transition system between sediment and soil, revealing an unusual link between sulfur-cycle and iron-oxidizing bacteria with plant root zones. Think of it like a bustling metropolis where different neighborhoods specialize in different functions—some areas focused on breaking down organic matter, others on cycling nutrients, all working together in perfect synchronization.

The Secret Sauce: Nutrient-Rich Lake Mud

The soil from the bottom of the lake was rich in nutrients, acting as an efficient and effective way of fertilizing the chinampas. But this wasn’t just any mud—it was a microbial goldmine. The canal muck was organically rich from rotting vegetation and household wastes. Every few months, farmers would dredge this black gold from the canal bottoms and spread it across their plots. Replenishing the topsoil with lost nutrients provided for bountiful harvests. The process was like giving the soil a vitamin shot packed with billions of beneficial microorganisms. Due to their humidity and high organic matter content, chinampa soils are characterized by considerable aerobic microbial activity and high oxygen consumption. This created the perfect environment for soil microbes to thrive and multiply.

Water: The Invisible Highway for Microbes

In a chinampa, canal water rises through capillary action to plant roots, reducing irrigation demand. But water did more than just hydrate plants—it served as a superhighway for microbial communities. A considerable portion of soil fertility is generated in the canal floors. The constant moisture created microgradients where different types of bacteria could establish specialized niches. Aerobic bacteria thrived near the surface where oxygen was abundant, while anaerobic species colonized deeper layers. Frequent irrigation increases greenhouse gas emissions as denitrification is stimulated and anaerobic microsites are created. This might sound problematic, but these anaerobic zones were actually crucial for completing nutrient cycles that modern agriculture often disrupts.

The Three Sisters and Their Microbial Partners

Three crops formed the staples of the Aztec diet: maize, beans and squash, with each plant assisting the others when grown together—corn takes nitrogen from the soil which beans then replace, bean plants need firm support which corn stalks provide, and luxurious squash leaves shade the soil keeping moisture in and weeds out. But the real magic happened underground. Each plant attracted different microbial communities to their root zones. Corn roots hosted bacteria that could break down complex organic compounds. Bean roots formed partnerships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria that could pull nitrogen directly from the air. Squash roots created extensive networks that helped distribute nutrients and water throughout the entire plot. Some scholars argue that chinampa systems are so successful due to the diversity of species used within plant beds, with one system including an astonishing 146 different plant species.

Continuous Cultivation Without Soil Exhaustion

Traditional chinampas are biodiverse, can be kept in almost continuous cultivation, their soils are renewable, and they create a microenvironment that protects crops from frosts. This defied everything we thought we knew about agriculture. How could you farm the same plot continuously for centuries without the soil becoming exhausted? The answer lay in the microbial partnerships the Aztecs unknowingly cultivated. Complex rotations allow up to seven harvests in a year. Each rotation brought different plants with different root microbiomes, constantly refreshing and diversifying the soil’s microbial community. It was like having a natural crop rotation system that operated at the microscopic level, ensuring that no single group of microbes ever became dominant enough to deplete specific nutrients.

Carbon Sequestration Champions

Chinampa soils sequester large quantities of carbon and are becoming a relevant strategy in Mexico City’s efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Modern research has revealed that these ancient farming systems were accidentally creating one of the most effective carbon storage systems on Earth. The constant addition of organic matter, combined with the unique water-logged conditions, created an environment where carbon could be stored in the soil for centuries rather than being released back into the atmosphere. Chinampas also provide ecosystem services, particularly greenhouse gas sequestration and biodiversity. The microbial communities in chinampa soils acted like microscopic carbon farmers, continuously processing organic matter and storing it in stable forms that could last for generations.

Temperature Regulation Through Microbial Activity

Traditional chinampas create a microenvironment that protects crops from frosts. While the water’s thermal mass provided some protection, recent research suggests that microbial activity played a crucial role in temperature regulation. The humidity generated by water deposited in canals and wetlands, combined with evapotranspiration of vegetation, promotes a more humid climate and less aggressive wind erosion in the microclimate. Active microbial communities generate heat through their metabolic processes, creating warm zones around plant roots that could protect crops during cold snaps. This biological heating system worked 24 hours a day, powered entirely by the decomposition of organic matter and the respiration of countless microorganisms living in the soil.

The Productivity Miracle Explained

Estimates suggest that 2.5 acres of chinampa gardening in the basin of Mexico could provide annual subsistence for 15–20 people. These productivity levels seemed impossible by conventional agricultural standards. The chinampa system is one of the most intensive and productive production systems ever developed and is highly sustainable. The secret wasn’t just the constant water supply or the fertile mud—it was the incredibly diverse and active microbial ecosystem that the Aztecs had unknowingly created. Other benefits include a damping down of plant diseases compared to ground-based agriculture. The diverse microbial communities acted like a natural immune system, outcompeting harmful pathogens and protecting plants from disease. It was biological warfare at the microscopic level, with beneficial microbes serving as tiny bodyguards for the crops above.

Modern Science Rediscovers Ancient Wisdom

Today, many cities face very similar challenges as Mexico City did 700 years ago—a rapidly growing population and less arable land available for food production, making highly intensive production systems with low resource demand a strategic goal. Scientists are now studying chinampa soils with advanced molecular techniques that the Aztecs could never have imagined. Current research aims to link molecular “omics” methods such as metagenomics, metatranscriptomics and metaproteomics with approaches based on soil chemical and biochemical analyses. What they’re finding is that the Aztecs inadvertently created some of the most sophisticated soil ecosystems ever documented. Soil is home to a multitude of microorganisms from all three domains of life, with these organisms and their interactions crucial in driving soil carbon cycling through Microbial Carbon Use Efficiency.

The Ecosystem Services Revolution

Besides food, chinampas provide a series of ecosystem services to Mexico City, including water filtration, water flow regulation and temperature regulation, as well as providing a refuge for regional biodiversity. Modern environmental scientists have discovered that the microbial communities in chinampa soils act like living water treatment plants. The dredging of mud cleared the way for canals and naturally reinvigorated soil nutrients, while the resulting system of canals and gardens created a habitat for fish and birds—the chinampas didn’t harm the environment, they enhanced it. These microbes can break down pollutants, filter heavy metals, and transform harmful compounds into harmless ones. It’s like having millions of tiny chemists working around the clock to keep the water clean and the soil healthy.

Biodiversity Hotspots in Miniature

The system stands out for having great biodiversity, housing 2% of the world’s biodiversity and 11% of national biodiversity with 139 species of vertebrates. But the real biodiversity treasure was hidden in the soil. Each handful of chinampa earth contained millions of different microbial species, many of which science has yet to identify or understand. If you look in a gram of soil, you have tens of thousands of different bacterial species—soil is the most diverse microbiome we know, more diverse even than the human gut. This incredible microbial diversity created a resilience that allowed chinampas to bounce back from floods, droughts, and other environmental stresses that would devastate monoculture farming systems.

Knowledge Keepers and Oral Traditions

Chinampas are traditionally built based on oral wisdom transmitted since the time of the Aztecs, with chinampero farmers preserving traditional prehispanic cultivation techniques that have been transmitted orally. The knowledge of how to manage these complex microbial ecosystems was passed down through generations, not in textbooks or scientific papers, but through hands-on experience and careful observation. Cultural practices associated with chinampas activities manifest beliefs and worldviews, with rituals and regional parties establishing forms and systems of identity within neighborhoods and extended families. The farmers didn’t understand bacteria or soil chemistry, but they understood the signs that indicated healthy soil—the smell of rich earth, the feel of proper texture, the colors that indicated balanced fertility. Their traditional practices unknowingly maintained optimal conditions for beneficial microbial communities to flourish.

Urban Agriculture’s Future Blueprint

The chinampa system is considered one of the most intensive and productive farming systems ever developed—a type of post-classic urban farming that some researchers say is a potential model of food production for the modern metropolis. As cities around the world struggle with food security and environmental degradation, the ancient wisdom of chinampa agriculture offers a roadmap for sustainable urban farming. They’re still in place around Mexico City as both tourist attractions and working farms, with other cities picking up on the chinampa idea—you can find them on the Baltimore waterfront and even cleaning up New York’s polluted Gowanus Canal. Modern adaptations are incorporating our new understanding of soil microbiology to optimize these systems for contemporary urban environments. It’s like upgrading ancient software with modern knowledge while keeping the core programming that made it so successful.

Challenges in the Modern World

For decades, chinampas have faced increasing threats due to urbanization, overexploitation of water resources, water contamination and unregulated tourism, as well as growing rejection of chinampa culture by traditional farmers and loss of ancestral knowledge. The delicate microbial ecosystems that took centuries to develop can be destroyed in just a few years by pollution or poor management. In Xochimilco, chinampas are at risk due to water contamination, excess salinity, and loss of soil moisture, making vegetables no longer fit for human consumption since waters have potentially toxic agents. When the water becomes contaminated, it doesn’t just affect the plants—it destroys the entire underground community of beneficial microbes that made the system work. Recovery can take decades, and in some cases, the original microbial diversity may be lost forever.

Lessons for Sustainable Agriculture Today

One of the most significant contributions of chinampa agriculture to modern farming is its sustainable approach, exemplifying a harmonious relationship between human activity and the natural environment through careful management of wetland ecosystem resources. Modern farmers are learning to think like the ancient Aztecs—not just about what they can take from the soil, but what they can give back to support the living communities beneath their feet. Key sustainable practices include organic fertilization using decomposed plant matter and fish remains to enrich soil, preserving soil health while minimizing synthetic fertilizers that can lead to soil degradation and water pollution. The chinampa model shows us that the most productive agriculture isn’t about dominating nature—it’s about becoming partners with the microscopic life that makes all terrestrial life possible.

The Carbon Storage Time Capsule

After cell death and subsequent lysis of soil microbes, some cell residues (microbial necromass) are persistently present and comprise slow-cycling carbon in grassland soil, with land use practices demonstrating positive impact on facilitating microbial turnover and persistence of microbial necromass. The Aztecs unknowingly created one of the most effective carbon storage systems on Earth. Every season, as microbial communities lived, died, and were replaced, their cellular remains became locked into the soil matrix. Chinampas could help reduce greenhouse gas emissions and maintain tropical wetlands while providing ecosystem services, especially carbon sequestration and increased agrobiodiversity. After 700 years, scientists can still find ancient carbon stored in chinampa soils—a testament to the stability of these microbial ecosystems. It’s like having a time capsule of atmospheric carbon, safely stored away by billions of microscopic workers who never knew they were helping to regulate Earth’s climate.

Resilience Through Diversity

Although microbial populations recovered after environmental disturbance with new bacteria being blown in by wind, the species that were active or dormant had changed compared with conditions before the disturbance. Modern research on soil recovery has revealed something remarkable about chinampa ecosystems—their incredible resilience comes from their diversity. Many people don’t realize that an incredible number of soil microbes are simply not active at any given time, with active microbes being the ones that contribute to ecosystem functions. It’s like having a vast reserve army of microorganisms waiting in the wings, ready to spring into action when conditions change. This built-in redundancy allowed chinampa soils to survive floods, droughts, volcanic eruptions, and even centuries of changing agricultural practices. The wisdom of maintaining microbial diversity as an insurance policy against environmental uncertainty is something modern agriculture is only beginning to appreciate.

The ancient chinampas were far more than just an ingenious farming technique—they were living laboratories where human ingenuity partnered with microbial intelligence to create something greater than the sum of its parts. Today, as we face challenges of climate change, soil degradation, and food security, the secrets locked in those ancient soils offer us a roadmap toward a more sustainable future. The microbes that made the chinampas possible are still there, waiting in the mud of Xochimilco’s canals, ready to teach us how to farm in harmony with the invisible majority that truly runs our planet. Did you imagine that the future of agriculture might be found in the wisdom of the past?