Deep in the Amazon rainforest, a mysterious, swirling brew is prepared in the hush of midnight. It’s called ayahuasca, and for centuries, Indigenous shamans have used it to unlock hidden realms of the mind. Now, scientists are finally catching up, peering through the jungle’s green veil to see what secrets these ancient plants might hold for the world. The story isn’t just about one vine or potion. It’s about an entire universe of psychoactive plants—each with its own legend, power, and potential to heal or transform. What are we really learning from the keepers of these botanical wonders, and how might their wisdom change the way we see ourselves, our minds, and even our place in nature?

The Ancient Roots of Plant Medicine

Long before laboratories and microscopes, Indigenous peoples were already experimenting with psychoactive plants, guided by tradition, ritual, and trial and error. From the dense jungles of South America to the arid plains of Africa, shamans and healers discovered which roots, vines, and leaves could open the mind or mend the spirit. These traditions are more than folklore—they are living libraries of medical knowledge. In many cultures, the use of hallucinogenic plants is tightly woven into spiritual beliefs, rites of passage, and community healing. Today, scientists are beginning to see that these practices hold real insights, not just about chemistry, but about how humans relate to their environment and each other.

Ayahuasca: The Vine of the Soul

Ayahuasca is perhaps the most famous Indigenous psychoactive plant brew. It’s made by boiling the Banisteriopsis caapi vine with leaves of the Psychotria viridis shrub. The resulting potion is thick, bitter, and wild with power. When consumed, it can lead to hours of vivid visions, deep introspection, and—some say—profound healing. Researchers have found that ayahuasca’s main active ingredient, DMT (dimethyltryptamine), interacts with serotonin receptors in the brain, producing its mind-bending effects. What’s remarkable is how the Indigenous knowledge accurately identified which plants to combine, creating a chemical synergy that unlocks DMT’s properties in the body.

DMT: The Spirit Molecule

DMT, often called “the spirit molecule,” is one of the most potent hallucinogens known. It’s found not just in ayahuasca, but in a surprising number of plants worldwide. When ingested by itself, DMT is quickly broken down in the stomach. But Indigenous peoples discovered that certain vines, like Banisteriopsis caapi, contain MAO inhibitors, chemicals that protect DMT and allow it to reach the brain. This discovery is nothing short of astonishing from a scientific perspective. Modern research is exploring DMT’s effects on consciousness—some studies suggest it can induce mystical experiences, reduce fear of death, and even help treat depression or PTSD.

Peyote and San Pedro: Cacti With a Visionary Edge

Travel north from the Amazon, and you’ll find other sacred plants in the deserts of Mexico and the Andes. Peyote and San Pedro are two cacti whose buttons or stems contain mescaline, a powerful psychedelic. Native American communities have used these plants for centuries in ceremonial settings, seeking visions, guidance, or healing. Mescaline creates a very different experience from ayahuasca—often described as more gentle, with enhanced colors and a deep sense of connection to nature. Scientists are now studying mescaline’s potential to treat addiction, anxiety, and other mental health challenges.

Psilocybin Mushrooms: Nature’s Hidden Teachers

Psilocybin mushrooms, sometimes called “magic mushrooms,” have been part of Indigenous rituals from Mexico to Siberia. In rituals, they’re often seen as a bridge between the physical and spiritual worlds. When eaten, psilocybin converts to psilocin, which alters perception, mood, and cognition. Modern medicine has taken note: recent clinical trials show psilocybin can rapidly reduce symptoms of depression, even in people who haven’t responded to other treatments. The echoes of ancient mushroom ceremonies can now be felt in today’s therapeutic clinics.

Iboga: The Root of Awakening

In West Africa, the Iboga plant holds a special, almost fearsome reputation. The root bark contains ibogaine, a compound known for its intense, dreamlike visions and its ability to help break the grip of addiction. The Bwiti religion uses iboga in initiation ceremonies, guiding participants through powerful journeys of self-discovery. Scientists studying ibogaine have found it can disrupt addictive patterns in the brain, sometimes after just a single dose. However, its use is not without risks—ibogaine can affect the heart, and careful medical supervision is essential.

Kava: The Drink of Peace

The South Pacific’s answer to psychoactive plants is kava, a root that’s ground into a milky drink. In Fiji, Vanuatu, and Tonga, kava ceremonies are used to welcome guests, settle disputes, and foster social harmony. The active compounds, kavalactones, have calming, anxiety-reducing effects without the mind-altering visions of other plants. Recent studies suggest kava can be as effective as pharmaceutical drugs for treating anxiety, with fewer side effects. The gentle nature of kava makes it a unique example of how plants can soothe the mind and bring people together.

Tobacco: More Than Just Smoke

Tobacco is often associated with addiction and health risks in the modern world, but among many Indigenous groups, it’s a sacred plant. Used in rituals, prayers, and healing, tobacco is believed to carry messages to the spirit world. The alkaloid nicotine is a powerful stimulant, but traditional use often involves small, controlled amounts, sometimes even as a snuff or in ceremonial pipes. Scientists are now exploring nicotine’s effects on attention, memory, and even neurodegenerative diseases, separating the plant’s ritual significance from its modern abuses.

Coca Leaves: Sacred Chew of the Andes

Coca leaves, the raw material for cocaine, have a much different meaning in their Indigenous context. Chewed or brewed as tea in the Andes, coca leaves provide a mild, stimulating effect—helping people cope with altitude and fatigue. The ritual use of coca is steeped in ceremony, gratitude, and respect for the earth. Recent research suggests that coca’s alkaloids have unique properties, and when used traditionally, they don’t carry the addictive punch of purified cocaine. The contrast between Indigenous and Western uses of coca is a powerful lesson in context and respect.

Yopo and Cebil: Snuffing Out the Ordinary

In the Orinoco basin and Gran Chaco, tribes prepare Yopo and Cebil snuffs from the seeds of Anadenanthera trees. These snuffs contain DMT and related compounds, and are blown into the nostrils during rituals. The effects are swift and intense—often described as a rush of visions, colors, and spiritual insight. Researchers are fascinated by the technology and botanical expertise involved in preparing these snuffs. They’re also uncovering how communal rituals can shape the psychedelic experience, making it safer and more meaningful.

The Role of Shamans: Guides and Healers

Shamans are the keepers and interpreters of plant wisdom. Their knowledge isn’t just about which plant to use, but how and when to use it, what songs to sing, and how to guide participants through challenging experiences. Science is beginning to recognize the importance of context, set, and setting—elements that Indigenous shamans have always emphasized. Without this guidance, even the most promising plant medicine can become overwhelming or even dangerous. The partnership between scientists and shamans is creating a new model for respectful, collaborative research.

Ritual, Ceremony, and Context: More Than Chemistry

One of the biggest lessons from Indigenous plant medicine is that the effects are not just about chemicals, but about the context in which they are used. Rituals provide structure, safety, and meaning. Songs, prayers, and group support can shape the experience, turning fear into insight or pain into healing. This holistic approach is influencing modern psychedelic therapy, where patients are prepared, supported, and guided throughout the process. The science is clear: mindset and environment matter just as much as the molecules themselves.

The Modern Psychedelic Renaissance

We’re living through a psychedelic renaissance—after decades of prohibition, research on psychoactive plants is booming. Universities and hospitals are running clinical trials with ayahuasca, psilocybin, and mescaline. Results are promising: these plants can help with depression, PTSD, addiction, and existential distress. Scientists are also mapping the brain under the influence of these substances, revealing new circuits and patterns that could unlock mysteries of consciousness. It’s a thrilling time, but one that demands humility and respect for the cultures that kept these traditions alive.

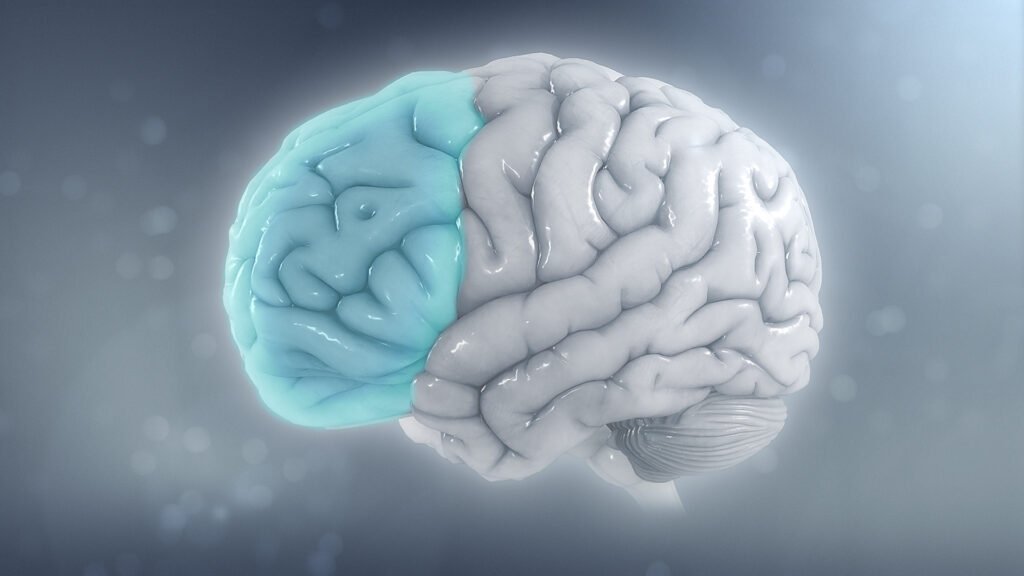

Scientific Insights Into Consciousness

Psychoactive plants don’t just heal—they challenge our basic ideas about the mind. MRI studies show that these plants can “quiet” the brain’s default mode network, often associated with ego and rumination. This can lead to feelings of unity, awe, or even ego dissolution. Psychologists are using these findings to explore the roots of creativity, spirituality, and even the sense of self. The plants, in a sense, are becoming teachers for the scientists, prompting new questions about what it means to be human and conscious.

Potential Medical Breakthroughs

The therapeutic potential of Indigenous psychoactive plants is staggering. Clinical trials are exploring their use in treatment-resistant depression, anxiety in terminal illness, substance abuse, and more. For example, psilocybin is showing promise for helping people quit smoking, while ayahuasca may help those struggling with trauma. These are not miracle cures, but the results so far are inspiring. The hope is that by combining ancient wisdom with modern science, we can develop new, more compassionate approaches to mental health.

Risks and Side Effects: A Balanced Perspective

It’s important not to romanticize these plants—there are real risks involved. Some, like ibogaine, can affect the heart or interact dangerously with other medications. Psychological challenges, such as anxiety or paranoia, can occur if the experience is poorly managed. Indigenous traditions have developed safeguards, such as dietary restrictions and careful supervision, to reduce these risks. Modern medicine is learning to respect and adapt these practices, ensuring safety as these substances move into wider use.

Cultural Appropriation and Respect

As interest in psychoactive plants grows, there’s a risk of cultural appropriation—taking sacred traditions out of context or commodifying them. Indigenous leaders are calling for more respect, collaboration, and benefit-sharing. Some organizations are working to ensure that traditional knowledge holders are partners, not just subjects, in research and commercialization. The conversation around ayahuasca and similar plants is not just about science, but about ethics, justice, and the ongoing impact of colonialism.

Legal and Ethical Challenges

The legal status of psychoactive plants varies wildly around the world. Some, like peyote, are protected for ceremonial use by Native Americans, while others remain strictly banned. Researchers must navigate a maze of regulations, often working in partnership with Indigenous communities to ensure ethical and legal compliance. The evolving legal landscape reflects shifting attitudes about drug policy, mental health, and the rights of Indigenous peoples. It’s a delicate balance between access, safety, and respect for tradition.

Conservation: Protecting the Plants and Their Habitats

With rising interest comes a new threat: overharvesting and habitat destruction. Many of these plants, like peyote and ayahuasca, are slow-growing and vulnerable to exploitation. Conservationists are sounding the alarm, warning that unsustainable demand could wipe out wild populations. Some Indigenous groups are leading efforts to protect and replant these species, blending traditional stewardship with modern conservation science. Safeguarding the plants means safeguarding the cultures and ecosystems they support.

The Future: Towards a New Synthesis

The frontier of Indigenous psychoactive plant research is wide open. Scientists and shamans, therapists and conservationists, are all part of an unfolding story. The lessons are clear: respect tradition, honor the plants, and proceed with humility. By weaving together ancient knowledge and modern science, we stand at the threshold of new ways to heal, understand, and connect. The question is no longer whether these plants have something to teach us, but whether we’re truly ready to listen.