Imagine stepping into Australia 50,000 years ago and coming face-to-face with creatures that would make today’s wildlife look like toys. Picture a kangaroo standing taller than a basketball hoop, weighing as much as a small car, staring at you with forward-facing eyes like a predator. Nearby, a marsupial lion the size of a jaguar sharpens its retractable thumb claws on tree bark, while a monitor lizard longer than a school bus basks in the sun. This wasn’t a scene from a fantasy movie—this was Australia during the Pleistocene epoch, when giants ruled the land.

The Giants Among Us: When Australia Was Supersized

Australia’s megafauna were unique, and included giant marsupials, huge flightless birds and giant reptiles. These massive animals weren’t just larger versions of today’s creatures—they were evolutionary marvels that had adapted to a very different Australia. The term Australian megafauna refers to the megafauna in Australia during the Pleistocene Epoch. Most of these species became extinct during the latter half of the Pleistocene, as part of the broader global Late Quaternary extinction event and the roles of human and climatic factors in their extinction are contested. Think of it like nature’s own experiment in supersizing—everything from kangaroos to wombats, lizards to lions, grew to proportions that would seem impossible today. As First Nations people have been in Australia over the past 60 000 years, megafauna must have co-existed with humans for at least 30,000 years. For social, spiritual and economic reasons, First Nations peoples harvested game in a sustainable manner.

Meet Procoptodon: The Kangaroo That Couldn’t Hop

Procoptodon goliah (the giant short-faced kangaroo) is the largest-known kangaroo to have ever lived. It grew 2–3 metres (7–10 feet) tall, and weighed up to 230 kg (510 lb). But here’s where it gets really wild: this massive marsupial couldn’t actually hop like modern kangaroos. Procoptodon was not able to hop as a mode of transportation, and would have been unable to accelerate sufficiently due to its weight. Broad hips and ankle joints, adapted to resist torsion or twisting, point to an upright posture where weight is supported by one leg at a time. Instead of bouncing across the landscape, these giants walked upright like early humans, using their massive single-toed feet—almost like horse hooves—to navigate the terrain. It had an unusually short, flat face and forwardly-directed eyes, with a single large toe on each foot (reduced from the more normal count of four). Each hand had two long, clawed fingers that would have been used to bring leafy branches within reach. Picture a kangaroo that looked more like a giant, two-legged horse with arms—and you’re getting close.

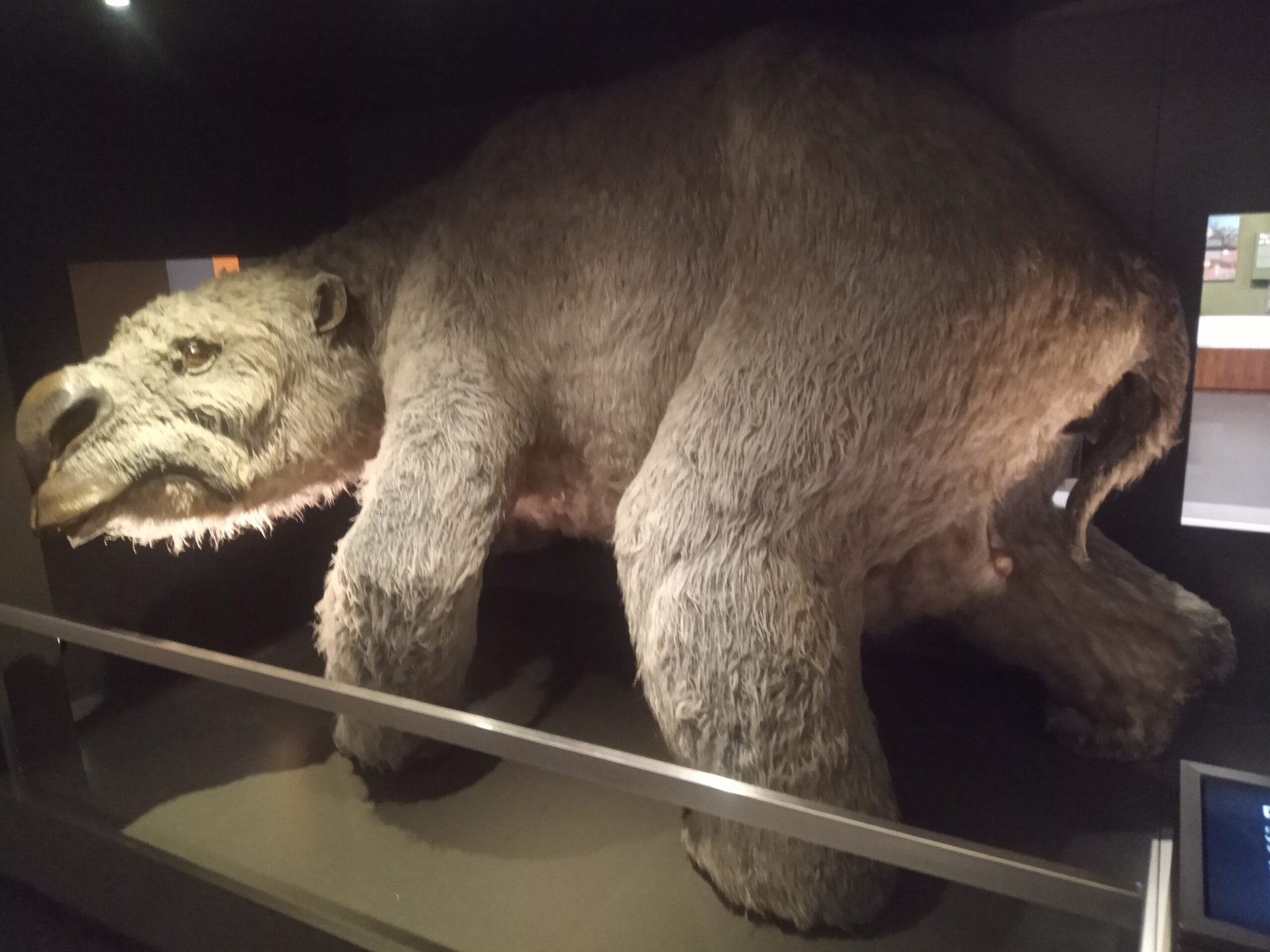

The Wombat That Was Actually a Tank

When we talk about “wombat tanks,” we’re referring to creatures like Diprotodon and the true giant wombats like Ramsayia magna. The massive Diprotodon optatum, from the Pleistocene of Australia, was the largest marsupial known and the last of the extinct, herbivorous diprotodontids. At just under 4 metres in length and up to 2800 kilograms in weight, Diprotodon, although massive, was smaller than either a hippopotamus (up to 4500 kilograms in weight) or rhinoceros (up to 3600 kilograms in weight), to which it is often compared. But Diprotodon wasn’t actually a true wombat—it was more like a massive, car-sized cousin. Diprotodon is an extinct megafauna species that is often referred to as Australia’s ‘giant wombat’. While Diprotodon were definitely giant, being the largest marsupials of all time, the car-sized animals were only distantly related to wombats. The real giant wombats, like Ramsayia magna, were more like armored bulldozers. Ramsayia magna, which lived in Australia during the late Pleistocene (about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago) was a true giant wombat. In a study published today in Papers in Palaeontology, we describe the most complete skull of one of these giant wombats, a hitherto poorly known species called Ramsayia magna.

Marsupial Lions: Nature’s Perfect Killing Machines

Thylacoleo (“pouch lion”) is an extinct genus of carnivorous marsupials that lived in Australia from the late Pliocene to the Late Pleistocene (until around 40,000 years ago), often known as marsupial lions. They were the largest and last members of the family Thylacoleonidae, occupying the position of apex predator within Australian ecosystems. The largest and last species, Thylacoleo carnifex, approached the weight of a lioness. But calling them “lions” is misleading—these weren’t cats at all. It may have been an ambush predator or scavenger, and had enormous slicing cheek teeth, large stabbing incisor teeth (replacements for the canine teeth of other carnivorous mammals) and a huge thumb claw that may have been used to disembowel its prey. Imagine a creature that combined the climbing ability of a leopard with the jaw power of a hyena and retractable thumb claws that could slice through flesh like butter. In size, an adult Thylacoleo would have been about as large as a jaguar. Thylacoleo had a very broad head and immensely powerful jaws. The bite force of Thylacoleo has been estimated to be comparable to that of the considerably larger male African lion.

Megalania: The Dragon That Actually Existed

Megalania (Varanus priscus) is an extinct species of giant monitor lizard, part of the megafaunal assemblage that inhabited Australia during the Pleistocene. It is the largest terrestrial lizard known to have existed, but the fragmentary nature of known remains make estimates highly uncertain. Think of a Komodo dragon that hit the gym for a few million years and decided to supersize everything. Recent studies suggest that most known specimens would have reached around 2–3 m (6.6–9.8 ft) in body length excluding the tail, while some individuals would have been significantly larger, reaching sizes around 4.5–7 m (15–23 ft) in length. Judging from its size, it would have fed mostly upon medium- to large-sized animals, including any of the giant marsupials such as Diprotodon, along with other reptiles and small mammals, as well as birds and their eggs and chicks. This wasn’t just a big lizard—it was a walking nightmare for anything else trying to survive in ancient Australia. Megalania is thought to have had a similar ecology to the living Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) which may be its closest living relative.

A Landscape of Giants: The Complete Ecosystem

Australia’s megafauna wasn’t just a random collection of big animals—it was a complete ecosystem where giants ruled every niche. Prior to that time, were 1,000-pound kangaroos in Australia, 2-ton wombats, 25-foot-long lizards, 400-pound flightless birds, 300-pound marsupial lions and Volkswagen-sized tortoises. You had massive herbivores like Diprotodon browsing in herds, giant kangaroos hopping—or rather walking—through open woodlands, and predators like Thylacoleo and Megalania keeping the ecosystem in balance. Australia’s Quaternary megafauna were unique, and included giant marsupials such as Diprotodon, huge flightless birds such as Genyornis (a distant relative to today’s ducks and geese) and giant reptiles such as Varanus ‘Megalania’ (related closely to living goannas and the Komodo Dragon). The sheer scale of these creatures is hard to comprehend—imagine a safari where every animal is at least three times larger than anything you’d see in Africa today.

The Mysterious Timing: When Did the Giants Disappear?

Most of these species became extinct during the latter half of the Pleistocene, as part of the broader global Late Quaternary extinction event and the roles of human and climatic factors in their extinction are contested. The timing of this mass extinction is one of the most hotly debated topics in paleontology. This suggests humans could have been responsible for wiping out the country’s megafauna between 50,000 and 40,000 years ago. This suggests there was not a long period of coexistence between the giant animals and early humans, and that Australia’s megafauna could have been rapidly hunted to extinction during the period (60,000-45,000 years ago) when the first humans reached the continent. But the story isn’t that simple. The youngest fossil remains of giant monitor lizards in Australia date to around 50,000 years ago. Some species may have survived much longer than others, creating a staggered extinction pattern that makes it difficult to pinpoint exactly when the last giants died out.

The Human Factor: Did Early Australians Hunt Giants to Extinction?

The arrival of humans in Australia around 60,000 years ago coincides suspiciously with the megafauna extinctions, but the relationship isn’t straightforward. He bases that idea on a 2006 study by Australian researchers, which indicated that even low-intensity hunting of Australian megafauna – like the killing of one juvenile mammal per person per decade – could have resulted in the extinction of a species in just a few hundred years. This “imperceptible overkill” theory suggests that even light hunting pressure could have driven these giants to extinction. Working with researchers at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, Dr Alistair Pike of Bristol’s Department of Archaeology and Anthropology analysed more than 60 megafauna bones and teeth found at Cuddie Springs in New South Wales. Cuddie Springs is central to the debate about the timing and cause of the megafaunal extinctions as it is the only site known in continental Australia where human artefacts and megafauna remains have been found in the same sedimentary layers. However, the evidence shows these massive creatures were particularly vulnerable—they were slow-breeding, highly visible, and in many cases, unable to escape quickly.

Climate Change: The Other Culprit

While humans played a role, climate change was simultaneously reshaping Australia’s landscape. At the end of the last ice age, Australia’s climate changed from cold-dry to warm-dry. As a result, surface water became scarce. Most inland lakes became completely dry or dry in the warmer seasons. This dramatic environmental shift would have been devastating for large animals that needed significant amounts of food and water. The study led by Professor Larisa DeSantis of Vanderbilt University posited that, despite being well-adapted for consuming flesh and bone, Thylacoleo was likely the victim of the drying out of Australia, which began about 350,000 years ago. The marsupial lions persisted for thousands of years afterwards, as more and more forests disappeared. Ultimately, the loss of forest habitats likely led to the extinction of these predators, with the last known record sometime between approximately 35 and 45 thousand years ago. For creatures like Thylacoleo that relied on forest ambush hunting, the loss of dense vegetation was a death sentence.

The Specialized Diets That Became Death Sentences

Many of Australia’s megafauna had evolved such specialized diets and lifestyles that they couldn’t adapt to rapid environmental changes. A trend to gigantism was likely in response to the gradual drying out of the Australian continent that started about 20 million years ago and the need to process poorer quality food such as grasses – harder to ingest than leaves and fruits. Take Procoptodon, for example—its massive jaws and specialized teeth were perfect for processing tough vegetation, but when the plants they depended on disappeared, they couldn’t switch to alternatives. P. goliah, depending heavily on free-standing water, was more vulnerable to drought. This can explain why the red kangaroo survived the increasing aridity and P. goliah did not. The very adaptations that made these animals successful giants also made them evolutionary dead ends when the environment shifted too quickly.

Island Gigantism: Why Australia Bred Such Monsters

Australia’s isolation played a crucial role in creating these supersized creatures through a phenomenon called island gigantism. Cut off from other continents for millions of years, Australia’s animals evolved without the competitive pressure from placental mammals that dominated elsewhere. The ancestors of thylacoleonids are believed to have been herbivores, something unusual for carnivores. They are members of the Vombatiformes, an almost entirely herbivorous order of marsupials, the only extant representatives of which are koalas and wombats, as well as extinct members such as the diprotodontids and palorchestids. This unique evolutionary pathway allowed marsupials to diversify into ecological niches that were filled by very different animals on other continents. The result was a menagerie of creatures that seems almost impossible—herbivorous ancestors giving rise to apex predators, and small ground-dwellers evolving into giants that rivaled the largest mammals anywhere on Earth.

The Fossil Evidence: Piecing Together the Puzzle

Understanding these creatures requires detective work with fragmentary fossil evidence. However, skeletal remains of Megalania are fragmentary, and much is unknown about its life history. No complete skeletons or intact skulls of Megalania are known, and the limited amount of skull material found to date was not associated with postcranial material. Vertebrae and isolated teeth are the most common fossils, and lower jaws and limb bones have also been found. Scientists have had to reconstruct these giants from scattered bones, isolated teeth, and occasional lucky finds like the complete Thylacoleo skeletons discovered in Nullarbor caves. In May 2002 a group of speleologist (people who explore caves), using an ultra-light aircraft, spotted cave openings in a remote part of the Nullarbor Plain. When they subsequently entered the caves they discovered numerous skeletons of extinct megafauna species, including one complete and a dozen incomplete skeletons of Thylacoleo. Each new discovery adds another piece to the puzzle, sometimes confirming theories and sometimes completely overturning them.

Chemical Clues: Reading Ancient Diets

Modern paleontology goes beyond just studying bones—scientists now analyze the chemical signatures preserved in fossilized teeth to understand what these animals ate and how they lived. By studying the chemical signature preserved within fossil teeth, the team was able to determine that the marsupial lion hunted primarily in forests, rather than open habitats. This is supported by features of the skeleton that indicate it was an ambush hunter, relying on catching its prey unaware rather than running them down across an open landscape. These chemical fingerprints can reveal whether an animal was a forest dweller or plains roamer, whether it ate grass or leaves, and even seasonal changes in diet. Chemical analysis of fragments of eggshells of Genyornis newtoni, a flightless bird that became extinct in Australia, from over 200 sites, revealed scorch marks consistent with cooking in human-made fires, presumably the first direct evidence of human contribution to the extinction of a species of the Australian megafauna. This kind of evidence provides the smoking gun that links human activity directly to extinctions.

The Survivors: Why Some Giants Made It

Not all of Australia’s large animals went extinct—some managed to survive the Pleistocene extinction event and live to this day. It is worth noting that not all megafauna are extinct – Australia has living megafauna in the form of Red and Eastern Grey Kangaroos. The key difference between survivors and victims often came down to flexibility. Modern kangaroos, for instance, can hop efficiently across long distances to find water and food, unlike their