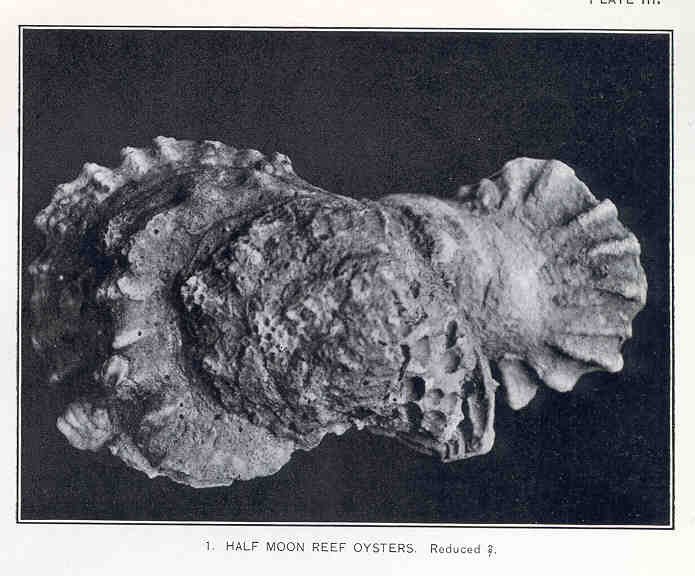

For decades, oyster reefs were considered relics of the past lost victims of overharvesting, pollution, and coastal development. But in a breathtaking find, scientists have revealed extensive, living oyster reefs running along Australia’s tropical north, some covering as much as five hectares and comparable to football fields in size. These reefs, concealed in plain sight, are not only surviving, they’re thriving in waters where few thought they could be found.

What adds to the fascination of this discovery is that until now, no one had officially named the reef-building species.The genetic analysis detected a close Sydney rock oyster relative, also known as “Saccostrea Lineage B,” to be the primary builder of such tropical reefs.However, due to their critical ecological role, these reefs do not have adequate protection a oversight in marine conservation that scientists are hurrying to rectify.

Why Did No One Notice These Reefs Before?

Oyster reefs have suffered catastrophic declines worldwide, with 85% lost globally due to dredging, overfishing, and habitat destruction. In temperate zones, reefs were stripped for lime production or cleared for shipping lanes. But in Australia’s tropical north, these reefs escaped industrial exploitation not because of careful management, but sheer luck.

The dominant reef-building oyster, Lineage B, was too small to attract commercial aquaculture. Unlike their southern counterparts, these reefs were never burned for lime or smothered by urban runoff. Instead, they persisted unnoticed, quietly filtering water and sheltering marine life while scientists focused on coral reefs and mangroves.

A Genetic Detective Story: Identifying the Mystery Oyster

Oysters are experts at camouflage. People of the same species can appear quite different from one another, whereas unrelated oysters can appear identical. To unravel this mystery, scientists consulted DNA analysis, taking samples of reefs at Wilson Beach, Turkey Beach, and Mapoon in Queensland.

The results were clear: Lineage B was the chief engineer at all three sites, with a few supporting players like leaf oysters and pearl oysters in the mix. This discovery rewrites the map of Australia’s reef-building species, proving that tropical oysters are far more ecologically significant than previously believed.

How Big Are These Reefs And Where Are They Hiding?

Employing drone surveys and ground level measurements, researchers confirmed that the reefs are some of the world’s largest intertidal oyster systems remaining in Australia. While coral reefs prosper underwater, the oyster beds are on land at low tide, composed of rough, wave-resistant ridges that reach across hectares.

Since launching The Great Shellfish Reef Hunt in 2024, scientists and citizen scientists have already pinpointed over 60 new reefs across Queensland, the Northern Territory, and Western Australia. Some are so expensive they can be seen from satellite imagery yet until now, they were absent from marine atlases.

The Unsung Heroes of Coastal Health

Oyster reefs are nature’s water filters, a single oyster can purify up to 50 gallons (190 liters) of water per day. They also act as nurseries for fish, buffer shorelines against storms, and lock away carbon in their shells. In southern Australia, where reefs have been reduced by 99%, restoration projects are painstakingly rebuilding lost habitats.

But in the tropics, these reefs never disappeared, they’ve been silently sustaining marine ecosystems for centuries. The question now is whether they’ll survive the next wave of threats: dredging, coastal development, and climate change.

A Race Against Time: Protecting Australia’s Last Great Oyster Reefs

Although they contribute significantly to ecological function, tropical oyster reefs lack official protection. They don’t appear as threatened ecosystems on the list, unlike coral reefs or seagrass meadows, and therefore are subject to unregulated destruction.

Scientists are now advocating for immediate conservation actions, including:

- Mapping all extant reefs via citizen science campaigns.

- Including them in biodiversity surveys to obtain legal protection.

- Scaling up restoration activities to guarantee their survival in warming oceans.

How You Can Help: Join the Great Shellfish Hunt

Researchers are asking beachgoers, fishermen, and people living in coastal communities to report oyster reef sightings. By posting images and locations on The Great Shellfish Reef Hunt, ordinary Australians can help complete essential knowledge gaps before such reefs suffer irreversible loss.

These recently discovered reefs are a welcome ecological bright spot evidence that nature can still flourish when provided with an opportunity. But unless immediate action is taken, they might disappear before we have a complete appreciation of how crucial they are. The time to save Australia’s tropical oyster reefs is now before history repeats itself and another important ecosystem passes us by undetected.

Did You Know?

- Oyster reefs support 300% more marine life than bare seabeds.

- Globally, oyster populations have declined by 85-99% over the past two centuries.

- A single hectare of oyster reef can filter 2.5 million liters of water daily equivalent to 10 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Want to get involved? Visit The Great Shellfish Reef Hunt and help document these hidden marvels before it’s too late.

Sources:

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.