Picture this: you’re walking along a beach at sunset, feeling like you’ve discovered something special about this moment in time. But what if I told you that on the universe’s timeline, you haven’t just shown up fashionably late to the party – you’ve arrived when the confetti is already being swept up? The story of life and time on a cosmic scale is more mind-bending than any science fiction novel, and spoiler alert: we humans are the ultimate latecomers to an epic 13.8-billion-year celebration.

The Universe’s Grand Opening Night

The universe burst into existence 13.8 billion years ago in what we call the Big Bang, but calling it a “bang” is like describing Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 as “some noise.” This wasn’t just an explosion – it was the birth of space, time, matter, and energy all rolled into one spectacular cosmic debut. The universe expanded faster than the speed of light for a fraction of a second during cosmic inflation, and within one second after the Big Bang, the universe consisted of an extremely hot primordial soup of light and particles at 18 billion degrees Fahrenheit. Think of it as the ultimate pressure cooker situation, where even atoms couldn’t form because everything was too hot and chaotic. The cosmos was opaque because a vast number of electrons created a sort of fog that scattered light, but when electrons bound into atoms, the cosmic fog cleared and the universe became transparent for the first time. This cosmic clearing happened about 380,000 years after the Big Bang – imagine waiting over a third of a million years just to see clearly! Stars didn’t exist for perhaps hundreds of millions of years after this cosmic recombination, during a period known as the Dark Ages.

When Darkness Ruled the Cosmos

The “Dark Ages” spanned a period during which the temperature of cosmic microwave background radiation cooled from some 4,000 K down to about 60 K. This wasn’t your typical blackout – it was a cosmic-scale power outage that lasted for millions of years. During this time, the universe was essentially a vast, dark, and cold space filled with hydrogen and helium gas, waiting for something extraordinary to happen. Around 100 million years after the Big Bang, ordinary matter particles began falling into the structures created by dark matter, and reionization began as smaller stars and larger non-linear structures like quasars began to take shape. The universe was like a massive construction site where the foundation was being laid for everything we see today. The first stars began to shine between 200-300 million years after the Big Bang, and because many were Population III stars, they were much bigger and hotter than modern stars and had fairly short lifecycles. These stellar pioneers were the universe’s first light bulbs, finally illuminating the cosmic darkness.

The First Stars Light Up the Show

The oldest-known confirmed star, SMSS J031300.36−670839.3, formed around 200 million years after the Big Bang, and by 300 million years, the first large-scale astronomical objects like protogalaxies and quasars began forming. These weren’t just any ordinary stars – they were cosmic giants that burned bright and fast, like rock stars who lived hard and died young. As Population III stars burned, stellar nucleosynthesis operated, with stars fusing hydrogen to produce helium, and over time being forced to fuse heavier elements up to iron, which when seeded into neighboring gas clouds by supernova, led to the formation of more Population II stars. Think of these early stars as cosmic chefs, cooking up the elements that would eventually become planets, oceans, and yes, even you and me. These Population III stars were responsible for turning the few light elements formed in the Big Bang into many heavier elements, and the larger stars had very short lifetimes, exploding as supernovae after mere millions of years. They were essentially cosmic factories with extremely short production runs, but they made the raw materials for everything that would come later.

Our Galactic Neighborhood Takes Shape

The thin disk of our galaxy began to form when the universe was about 5 billion years old, and the first stars in the thin disk region of the Milky Way formed around 5 or 6 billion years after the Big Bang. By this point, the universe had been through its awkward teenage years and was starting to look more like the cosmic neighborhood we know today. The Milky Way was finally born after a million-year process of stars coming together, and looking at this timeline, it’s surprising to observe that our Sun, born much later, is still incredibly young when compared to the age of the Milky Way. Our galaxy wasn’t built in a day – it was more like a cosmic urban development project that took billions of years to complete. The galactic disk of the Milky Way is estimated to have been formed 8.8 billion years ago, but the age of the Sun at 4.567 billion years is known precisely. This means our galaxy had already been around for over 4 billion years before our solar system even existed!

Our Solar System’s Late Arrival

The Solar System formed at about 9.2 billion years after the Big Bang (4.6 billion years ago), possibly triggered by a primal supernova, and the Sun formed around this time as the planetary nebula began accretion of planets. If the universe were a 24-hour day, our solar system would have shown up around 4:30 PM – definitely missing the morning rush and most of the afternoon activities. The oldest rocks on Earth have been dated to about 4.4 billion years old, approximating Earth’s formation just 4 days after the formation of the Solar System in cosmic calendar terms, and our Moon was formed just one day after us. Our cosmic address was relatively new real estate in an already established galactic neighborhood. The Sun is older than Earth, but it’s difficult to comprehend the massive age difference – saying Earth’s age is 4.5 billion years while the Sun’s age is 4.6 billion years doesn’t express how large that gap really is. In cosmic terms, that 100-million-year difference is like the difference between a newborn and a toddler.

Life’s Humble Beginnings on Earth

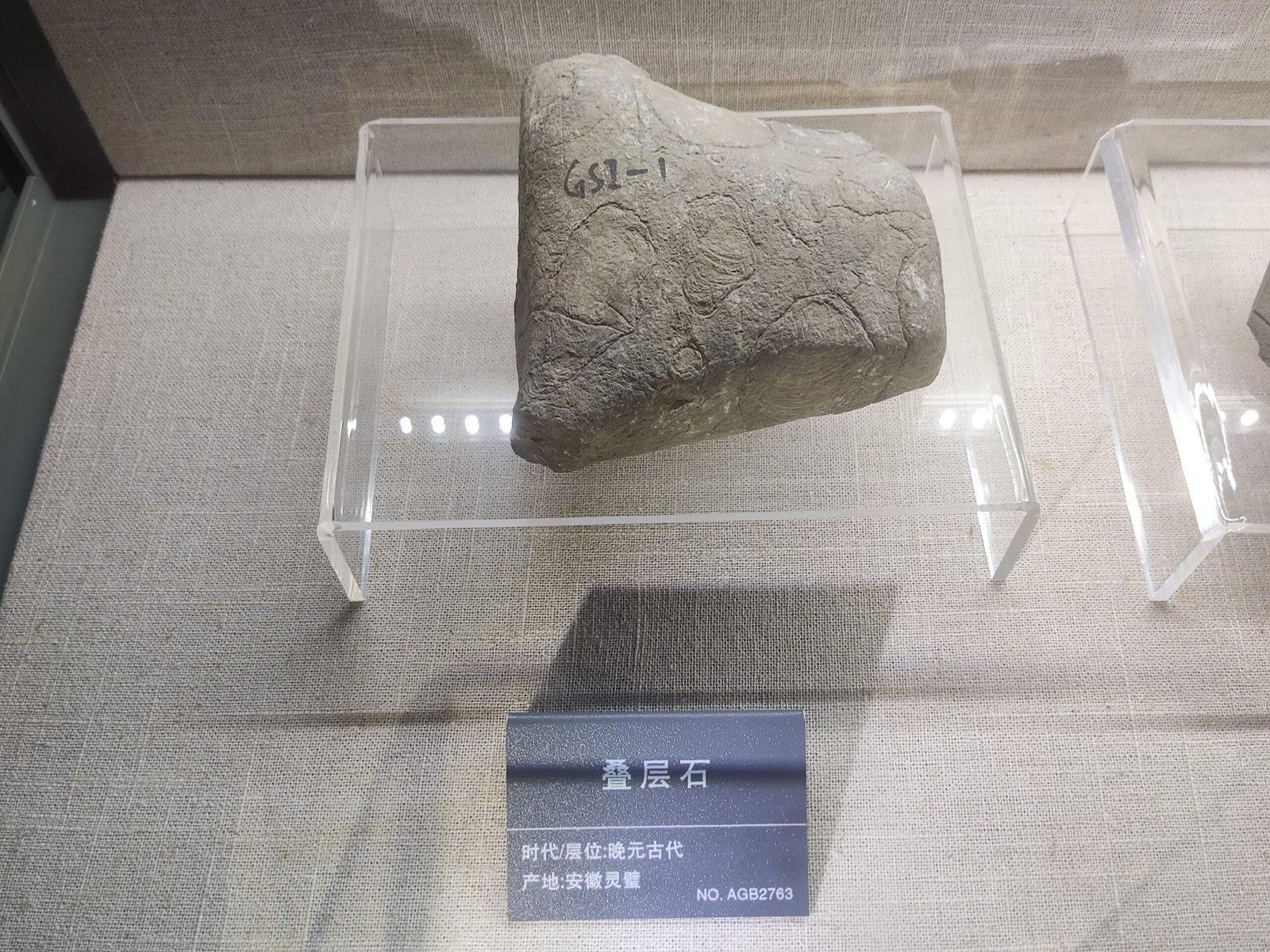

Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago and evidence suggests that life emerged prior to 3.7 billion years ago, with the earliest clear evidence of life coming from biogenic carbon signatures and stromatolite fossils discovered in 3.7 billion-year-old metasedimentary rocks. Life on Earth didn’t waste any time getting started – it was like the ultimate entrepreneurial success story, going from nothing to something extraordinary in less than a billion years. The earliest life forms we know of were microscopic organisms that left signals of their presence in rocks about 3.7 billion years old, consisting of a type of carbon molecule produced by living things, with evidence also preserved in hard structures called stromatolites dating to 3.5 billion years ago. These microscopic pioneers were the ultimate minimalists – no fancy features, no complex body plans, just the basic ability to survive and reproduce. Scientists have evidence that primitive single-celled organisms called prokaryotes first appeared between 3.8 and 3.5 billion years ago, and modern-day bacteria are related to these ancient prokaryotic microbes. These tiny organisms were essentially the universe’s first successful life experiment.

The Oxygen Revolution Changes Everything

The evolution of photosynthesis by cyanobacteria around 3.5 billion years ago eventually led to a buildup of oxygen in the oceans, and after free oxygen saturated all available reductant substances on Earth’s surface, it built up in the atmosphere, leading to the Great Oxygenation Event around 2.4 billion years ago. This wasn’t just a minor atmospheric adjustment – it was the equivalent of completely renovating the planet’s life support system. When cyanobacteria evolved at least 2.4 billion years ago, they became Earth’s first photo-synthesizers, making food using water and the Sun’s energy, and releasing oxygen as a result. Imagine if someone suddenly pumped your house full of a gas that was toxic to most life forms – that’s essentially what happened to Earth’s early inhabitants. The first known mass extinction was the Great Oxidation Event 2.4 billion years ago, which killed most of the planet’s obligate anaerobes. This was life’s first major plot twist, where the waste product of one group of organisms became the foundation for an entirely new way of living. The change to an oxygen-rich atmosphere was a crucial development, as life developed from prokaryotes into eukaryotes and multicellular forms.

Complex Cells Finally Arrive

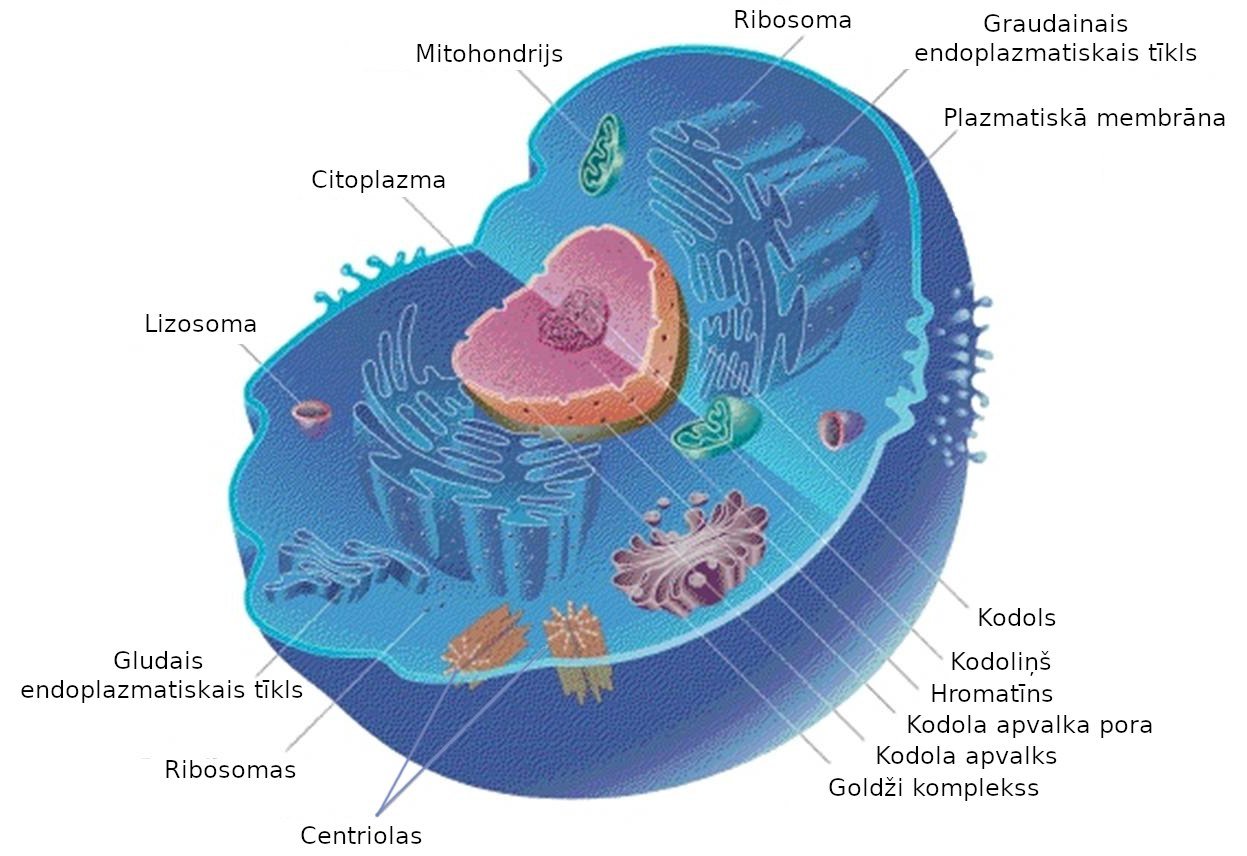

The earliest evidence of eukaryotes (complex cells with organelles) dates from 1.85 billion years ago, likely due to symbiogenesis between anaerobic archaea and aerobic proteobacteria, and while eukaryotes may have been present earlier, their diversification accelerated when aerobic cellular respiration provided a more abundant source of biological energy. This was like upgrading from a basic smartphone to the latest model with all the bells and whistles – suddenly, life had access to internal compartments, specialized functions, and much more sophisticated capabilities. Something revolutionary happened as microbes began living inside other microbes, functioning as organelles for them, with mitochondria evolving from these mutually beneficial relationships, and for the first time, DNA became packaged in nuclei. It was the ultimate cellular merger and acquisition deal, creating the corporate structure that would eventually lead to everything from mushrooms to blue whales. Eukaryotic cells are larger and more complex than prokaryotic cells, and around 2.4 billion years ago, the first proto-mitochondrion was formed when a bacterial cell related to today’s Rickettsia entered a larger prokaryotic cell. This cellular partnership was more successful than any business merger in human history.

The Long Wait for Multicellular Life

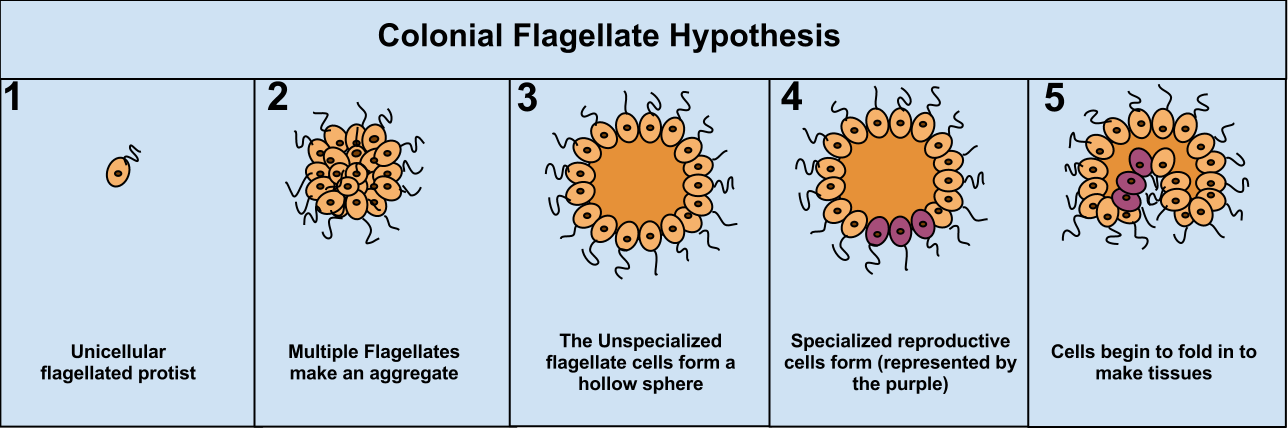

For more than a billion years, the timeline of life on Earth existed in primal forms, with all life being single-celled organisms made up mainly of bacteria and algae, until around 900 million years ago when simple multi-celled organisms started to appear. This was like living in a world where everyone was a freelancer for over a billion years before someone finally invented the concept of teamwork. Life remained mostly small and microscopic until about 580 million years ago, when complex multicellular life arose, developed over time, and culminated in the Cambrian Explosion about 538.8 million years ago. The transition from single cells to multicellular organisms was like going from individual musicians to forming a full symphony orchestra – suddenly, life could create much more complex and beautiful compositions. These newly formed organisms evolved from simpler organisms to have different types of cells with individual functions, marking a critical period in the evolution of planet Earth, as these organisms would evolve into all forms of life on Earth today. It was the moment when life learned the power of specialization and cooperation.

The Cambrian Explosion: Life’s Big Bang

540 million years ago a mysterious event occurred when suddenly, and seemingly out of nowhere, large numbers of species started appearing in what’s known as the Cambrian explosion, marking the first time animals with mineralized skeletal systems lived. This wasn’t just an increase in biodiversity – it was like life suddenly discovered the secret to architectural innovation and went completely wild with creative designs. In 1909, Charles Doolittle Walcott discovered the Burgess Shale fossils that revealed the unprecedented biodiversity of Cambrian life, with creatures like Waptia scouring the ocean bottom while Anomalocaris cruised above, and many odd-looking organisms like the 5-eyed Opabinia representing evolutionary experiments. It was nature’s most creative period, when life seemed to be throwing every possible body plan at the wall to see what would stick. The Cambrian explosion marked the rapid diversification of many new groups of multicellular organisms from a single common ancestor, with the term “explosion” referring to the sudden appearance of many new complex organisms in the fossil record over about 20 million years starting around 542 million years ago. In geological terms, 20 million years is incredibly fast – like going from horse-drawn carriages to space travel in a single human lifetime.

Life Conquers the Land

Soon after the Cambrian explosion, the first vertebrates appeared, followed by the emergence of life onto land rather than being confined to the oceans, and life on Earth was climbing in diversity with many new species of plants and animals separating onto different evolutionary paths. Moving from water to land was like humanity’s first steps on the moon – a giant leap that opened up entirely new possibilities for life. Plants began colonizing the land, fish began swimming in the seas, and the first life on land started as algae gradually adapting to live on dry land, with the first four-legged animals developing around 400 million years ago. The major groups of marine animals like mollusks and arthropods appeared about 541 million years ago at the base of the Cambrian Period, while plants and fungi appeared together in the Rhynie Chert of Scotland about 408-360 million years ago in the Devonian Period. These four-legged animals, known as tetrapods, became the ancestors to all birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians, with the first amphibians appearing soon after and living on sea floors and in shallow marine ecologies. Life was essentially learning to be amphibious long before military strategists ever thought of the concept.

The Rise and Fall of Giants

The Permian-Triassic extinction event killed most complex species 252 million years ago, but during recovery, archosaurs became the most abundant land vertebrates, with dinosaurs dominating the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods until the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago killed off the non-avian dinosaurs. The dinosaurs had their moment in the sun for over 160 million years – making human civilization’s few thousand years look like a weekend camping trip. Over the next few million years, evolution continued among mammals, with many species growing to enormous sizes as megafauna that populated the planet until around 10,000 years ago when unknown events wiped most of them from the face of the earth. These giants were like nature’s version of supersizing everything – imagine walking through a world filled with creatures that would make elephants look like house pets. Mass extinctions may have accelerated evolution by providing opportunities for new groups of organisms to diversify. Each extinction was like hitting the reset button on life’s video game, allowing new players to take the stage and try completely different strategies.

Humans: The Ultimate Late Arrivals

During the late Cenozoic era, around two million years ago, the first early human species evolved from an ape ancestral species, with anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) first appearing in the fossil record around 200,000 years ago, and all of known human history falling within the previous 10,000 years. If Earth’s history were compressed into a single year, humans would have shown up in the last few minutes of December 31st – talk about cutting it close! Within the scheme of the Cosmic Calendar, an average human life of 70-80 years is equivalent to approximately 0.16 cosmic seconds. That’s right – your entire life, with all its dramas, achievements, and experiences, amounts to less than one-fifth of a cosmic second. Carl Sagan extended the