Picture this: you’re walking through a forest when you stumble upon a chimpanzee sitting motionless, staring at the ground where scattered fruit lies just out of reach. The chimp had been holding a long stick moments before, but dropped it to grab at the fruit directly. Now, watching other chimps successfully use tools to collect the same fruit, this individual sits in what appears to be contemplation. Is this regret? Or are we simply projecting human emotions onto an animal that lacks our complex emotional framework?

The Complexity of Animal Emotions

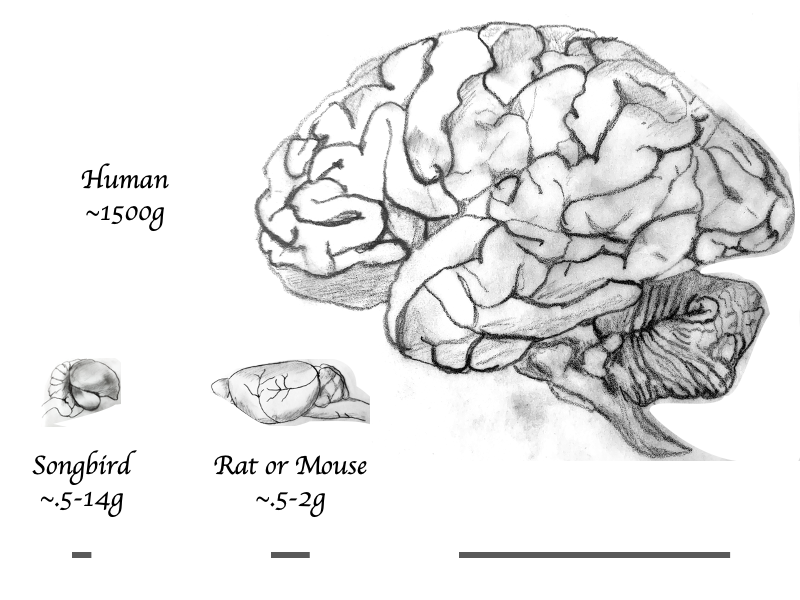

Scientists have long debated whether animals experience emotions similar to humans, and regret represents one of the most sophisticated emotional states to study. Regret requires not just memory of past events, but also the ability to imagine alternative outcomes and feel distress about choices made. This cognitive complexity involves multiple brain regions working together, including areas responsible for memory, decision-making, and emotional processing.

Recent advances in neuroscience have revealed that many animals possess neural structures remarkably similar to those associated with human emotions. The limbic system, which processes emotions in humans, exists in various forms across mammalian species. However, the presence of similar brain structures doesn’t automatically guarantee identical emotional experiences.

What Science Tells Us About Regret

Regret, as defined by psychologists, involves three key components: recognition that a different choice could have led to a better outcome, emotional distress about the choice made, and a desire to undo or change the decision. This emotional state requires what researchers call “counterfactual thinking” – the ability to imagine how things might have been different. For decades, scientists believed this level of cognitive sophistication was uniquely human.

Modern research has challenged this assumption through carefully designed experiments that test whether animals can demonstrate regret-like behaviors. These studies often involve choice scenarios where animals must decide between options, then observe whether they show signs of distress when their choice leads to a less favorable outcome than available alternatives.

Rats and the Restaurant Task

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence for animal regret comes from research conducted at the University of Minnesota. Scientists designed what they called the “Restaurant Row” experiment, where rats had to choose between different “restaurants” offering food rewards after varying wait times. The rats learned to skip restaurants with long wait times when they had limited time to forage.

The fascinating discovery came when researchers observed rats that had skipped a good deal and then encountered poor options afterward. These rats showed distinctive behavioral and neural patterns suggesting they were experiencing something akin to regret. Brain recordings revealed activity in the orbitofrontal cortex, the same region associated with regret in humans.

What made this study particularly convincing was that the rats’ behavior changed after these regret-like experiences. They became more likely to wait at restaurants they had previously skipped, suggesting they had learned from their apparent mistake and were motivated to avoid similar situations in the future.

Primate Problem-Solving and Second Thoughts

Primates, our closest evolutionary relatives, show perhaps the most compelling evidence of regret-like behaviors. Chimpanzees and bonobos have been observed in situations where they appear to reconsider their choices, especially in tool-use scenarios. When a chimp discards a tool and then realizes it was needed, the animal often shows signs of frustration and distress.

In laboratory settings, great apes have demonstrated the ability to learn from suboptimal choices in ways that suggest they understand the connection between their decisions and outcomes. Some studies have shown that when given the opportunity to “undo” a choice, apes will often do so, particularly when they can see that their initial choice led to a less favorable result than alternatives.

Dolphins and Their Social Calculations

Dolphins possess highly developed social intelligence and have been observed in behaviors that suggest they can anticipate and regret social decisions. Marine biologists have documented instances where dolphins appear to reconsider their actions, particularly in cooperative hunting scenarios where poor coordination leads to missed opportunities.

One particularly striking example involves bottlenose dolphins in Australia who use marine sponges as tools to forage on the seafloor. When young dolphins drop their sponges and lose foraging opportunities, they often return to the same area and search extensively for the lost tool. This behavior suggests they understand the connection between their careless action and the negative consequence.

The Corvid Connection

Crows, ravens, and other corvids demonstrate remarkable cognitive abilities that rival those of primates. These birds have been observed caching food and later returning to retrieve it, but sometimes they appear to make errors in their caching strategy. When crows discover that their cached food has spoiled or been stolen, they often show agitated behavior and may avoid similar caching locations in the future.

Research has shown that corvids can plan for future events and understand the consequences of their actions. When faced with tool-selection tasks, crows that make initial poor choices often show behavioral changes suggesting they recognize their mistake and are motivated to avoid repeating it.

Elephants and Emotional Memory

Elephants are renowned for their exceptional memory and complex emotional lives. Field observations have documented elephants returning to locations where they made decisions that led to negative outcomes, such as failed attempts to cross dangerous terrain or locate water sources. These visits often involve behaviors that suggest the elephants are processing the memory of their previous experience.

Particularly poignant examples involve elephant mothers who have lost calves due to predation or environmental hazards. Some researchers have observed these mothers returning repeatedly to the location where the loss occurred, showing behaviors that could be interpreted as regret or remorse about their inability to protect their young.

Cats and the Hunting Paradox

Domestic cats provide fascinating examples of behavior that might represent regret, particularly in their hunting activities. Cats often release prey and then attempt to recapture it, but sometimes the prey escapes entirely. In these situations, cats frequently display what appears to be frustration or regret, searching extensively for the lost prey and showing agitated behavior.

The complexity of feline hunting behavior suggests that cats understand the consequences of their actions and can anticipate outcomes. When their playful behavior leads to the loss of potential prey, their subsequent searching and calling behaviors might indicate they recognize their mistake and regret the outcome.

Dogs and Decision-Making Stress

Dog owners often report behaviors that seem to suggest their pets experience regret, particularly after making destructive choices. When dogs chew inappropriate items or have accidents indoors, they often display what appears to be guilt or regret through submissive postures and avoidance behaviors. However, scientific interpretation of these behaviors remains controversial.

Some researchers argue that what appears to be regret in dogs is actually a learned response to human disapproval rather than genuine emotional regret. However, other studies suggest that dogs can understand the connection between their actions and consequences, particularly in training scenarios where they learn to avoid behaviors that lead to negative outcomes.

The Neuroscience of Animal Regret

Brain imaging studies have revealed that many animals possess neural structures similar to those associated with regret in humans. The orbitofrontal cortex, which plays a crucial role in human regret, is present in various forms across mammalian species. Additionally, the anterior cingulate cortex, which processes emotional aspects of decision-making, shows similar patterns of activity in both humans and animals during choice scenarios.

These neurological similarities suggest that the capacity for regret-like experiences might be more widespread in the animal kingdom than previously thought. However, the presence of similar brain structures doesn’t guarantee identical emotional experiences, as the complexity and connectivity of these regions vary significantly across species.

Evolutionary Advantages of Regret

From an evolutionary perspective, the ability to experience regret would provide significant survival advantages. Animals that can learn from poor decisions and feel motivated to avoid similar mistakes would be more likely to survive and reproduce. This learning mechanism would be particularly valuable in complex environments where the consequences of decisions can be severe.

Regret also facilitates social learning and cooperation. Animals that can recognize when their actions have negatively affected group members or social relationships would be better equipped to maintain beneficial social bonds. This capacity would be especially important for species that rely on cooperation for survival.

The Mirror Test and Self-Awareness

The ability to experience regret is closely linked to self-awareness and the capacity for self-reflection. Many animals that show evidence of regret-like behaviors also pass the mirror self-recognition test, suggesting a connection between self-awareness and the ability to evaluate one’s own decisions. Great apes, elephants, dolphins, and some corvids all demonstrate varying degrees of self-recognition.

This connection between self-awareness and regret makes evolutionary sense, as animals need to understand themselves as agents of change in their environment to truly experience regret about their actions. The correlation between mirror test performance and evidence of regret-like behaviors suggests these cognitive abilities may have evolved together.

Cultural Learning and Regret

Some species that show evidence of regret also demonstrate cultural learning, where knowledge and behaviors are passed down through generations. This combination suggests that regret might play a role in cultural evolution, helping animals learn not just from their own mistakes but from observing the regretful behaviors of others.

Chimpanzees, for example, have been observed learning tool-use techniques partly through watching others make mistakes and show apparent regret. Young chimps seem to pay particular attention to the frustrated behaviors of adults who have made poor tool choices, suggesting they can learn from others’ regretful experiences.

The Skeptic’s Perspective

Despite compelling evidence, many scientists remain skeptical about animal regret. Critics argue that what appears to be regret might actually be simpler emotional responses like frustration or disappointment. They contend that true regret requires complex cognitive processes that may be uniquely human, including the ability to consciously reflect on alternative choices and their potential outcomes.

These skeptics point out that many apparent examples of animal regret can be explained through simpler mechanisms like associative learning, where animals learn to avoid situations that previously led to negative outcomes without necessarily experiencing the complex emotional state of regret. The challenge lies in distinguishing between genuine regret and these simpler forms of learning.

Implications for Animal Welfare

If animals can indeed experience regret, this has profound implications for how we treat them in captivity and in the wild. Animals capable of regret might suffer not just from immediate negative experiences but also from the ongoing emotional burden of poor decisions or missed opportunities. This understanding could reshape animal welfare policies and practices.

Zoos and research facilities might need to consider providing animals with more opportunities to make meaningful choices and learn from their decisions. Environmental enrichment programs could be designed to allow animals to experience the natural consequences of their choices while minimizing serious negative outcomes.

The Future of Animal Emotion Research

Advances in neuroscience and behavioral observation techniques are providing new insights into animal emotions. Brain imaging technology is becoming more sophisticated and less invasive, allowing researchers to study animal neural activity in more natural settings. These developments promise to shed new light on the question of whether animals experience regret and other complex emotions.

Additionally, long-term field studies are revealing increasingly complex behaviors in wild animals that suggest sophisticated emotional and cognitive abilities. As our understanding of animal cognition expands, we may discover that regret and other complex emotions are more common in the animal kingdom than we currently realize.

What This Means for Human Uniqueness

The possibility that animals experience regret challenges traditional notions of human uniqueness and superiority. If regret is not exclusively human, it suggests that our emotional experiences may be part of a broader evolutionary continuum rather than representing a fundamental break from the animal kingdom. This perspective encourages us to view animals as more complex and emotionally sophisticated than previously assumed.

However, even if animals do experience regret, human regret likely differs in its complexity and intensity. Our ability to imagine multiple alternative scenarios and engage in complex reasoning about our choices probably makes human regret more elaborate than anything experienced by other animals. The question isn’t whether we’re unique, but rather how we’re different.

Conclusion

The evidence suggests that humans are not alone in experiencing regret-like emotions. From rats learning from missed opportunities to elephants revisiting scenes of past tragedies, many animals show behaviors that strongly suggest they can recognize poor decisions and feel distressed about them. While the full complexity of human regret may remain unique to our species, the basic emotional experience appears to be shared across many intelligent animals.

This understanding fundamentally changes how we view our relationship with other species and our responsibilities toward them. If animals can experience regret, they possess a level of emotional sophistication that demands our respect and consideration. The question isn’t just whether animals feel regret, but how this knowledge should shape our treatment of them. What does it mean for our moral obligations when we recognize that animals might suffer not just from what we do to them, but from the weight of their own difficult decisions?