A skull pulled from deep time can still jolt the present. Curators whisper about its mix of features; researchers argue over what, exactly, those features mean. Is this the face of an encounter between modern humans and Neanderthals, or just the tricky overlap of traits we’ve long learned to expect in the Pleistocene? The mystery matters because it challenges how we read bones, genes, and the tangled routes our ancestors traveled. If the evidence holds, it could turn a museum specimen into a milestone – and force us to rethink what “human” looked like on a cold evening forty or fifty thousand years ago.

The Hidden Clues

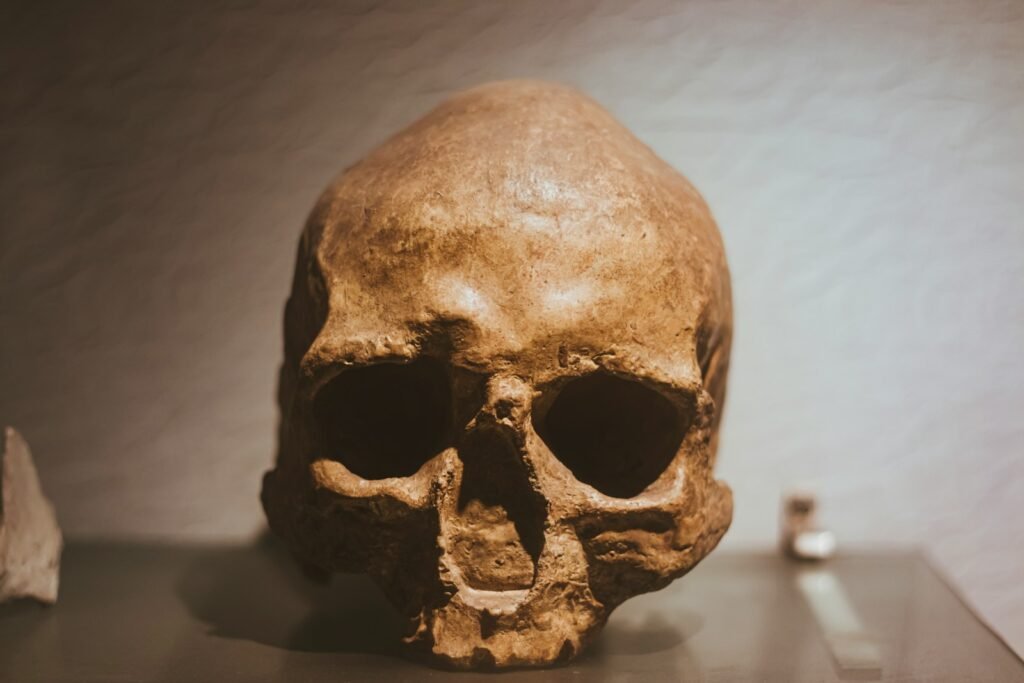

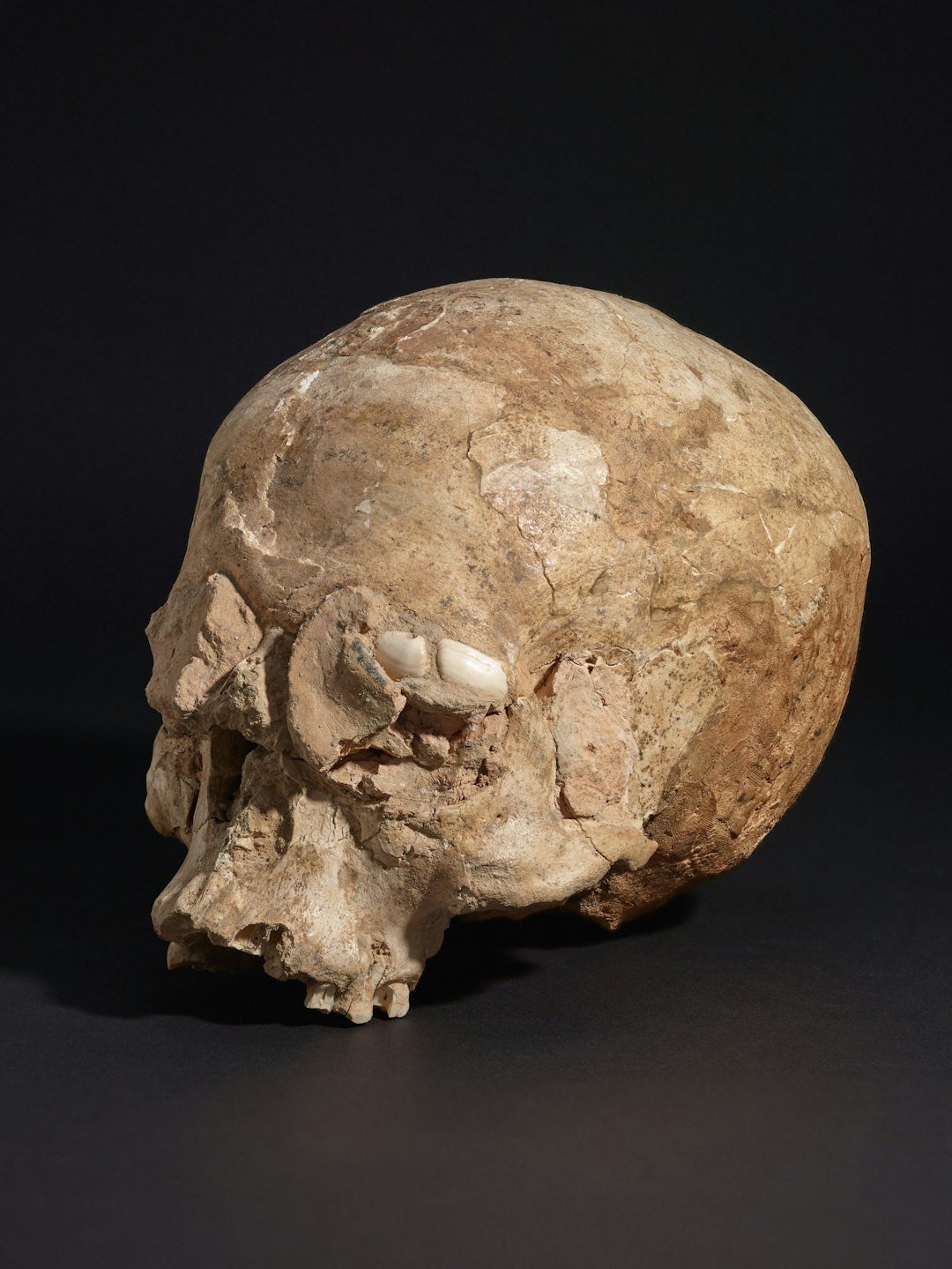

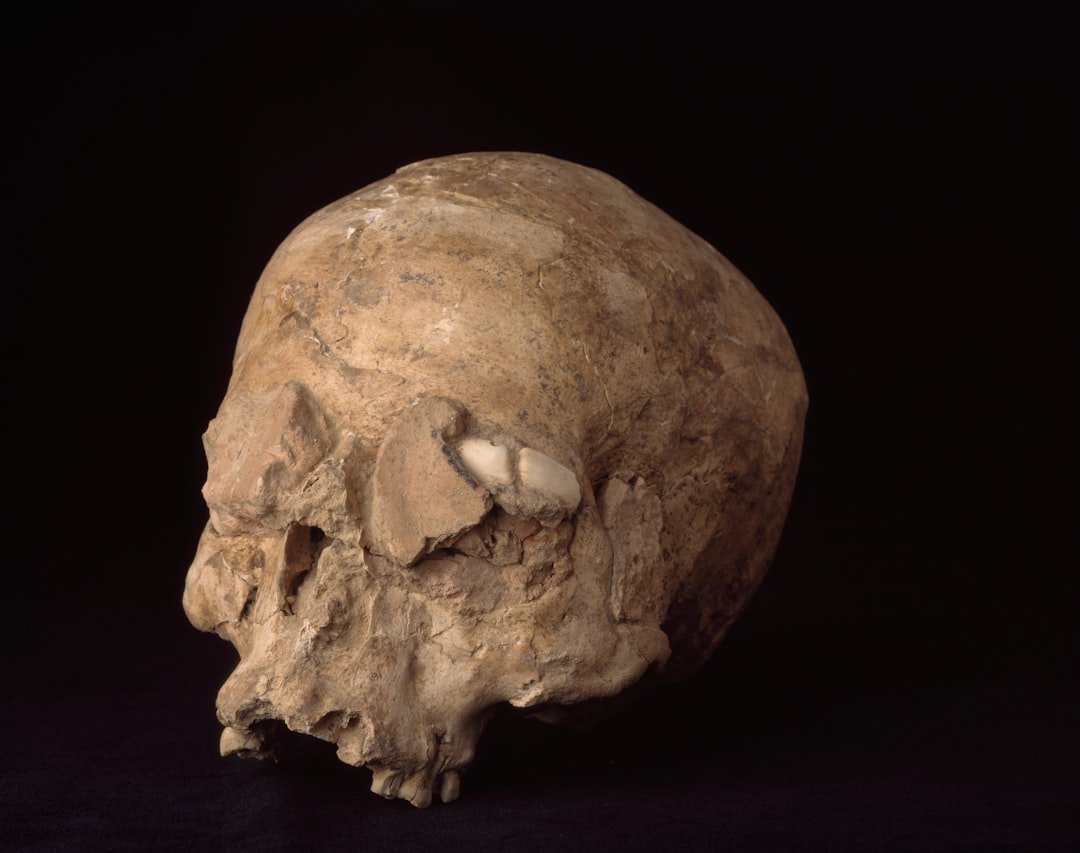

At first glance the cranium looks familiar – rounded like ours – but then your eye catches a subtle shelf of bone at the rear, the hint of an occipital bun. The brow seems a touch heavy, not the classic Neanderthal bar, yet sturdier than the average modern forehead. The jaw tells its own story: a defined chin suggests our species, while a roomy back-of-jaw space hints at something older. It’s a mosaic, the type of pattern that makes paleoanthropologists both excited and cautious.

I’ve stood in small regional museums where similar skulls sit in quiet cases, daring visitors to choose a label. The truth is, transition periods blur lines. Bones can look like optical illusions where lighting, angle, and expectation change what you think you see. That’s why this skull has become a lightning rod: it invites interpretation – and demands restraint.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

Context is king. The sediments around a fossil can carry stone tools, hearth ash, even pollen that date the layer and hint at who lived there. Neanderthals tended toward prepared-core techniques and robust points; early modern humans favored long blade production and ornaments that traveled far. But toolkits are not DNA, and cultural borrowing muddies the picture when neighbors share ideas across campfires.

Today’s lab methods narrow that uncertainty. High-resolution CT scans map internal bone architecture; geometric morphometrics quantify shape rather than relying on the naked eye. Meanwhile, radiocarbon dating has improved for tricky, collagen-poor bones, and proteomics can sometimes step in when DNA fails. The result is a richer, multi-lens view that can test bold claims without jumping to them.

The Skull at the Center

What exactly makes a skull trigger the hybrid question? Start with the cranium’s overall globularity, a hallmark of our species, and set it against localized Neanderthal-like features such as a projecting mid-face or the faint trace of a retromolar gap. Add dental wear patterns that look distinctly Pleistocene, not Holocene, and you have a profile that refuses a simple badge. The specimen’s preservation in a disturbed layer only raises the stakes, because provenance can make or break an extraordinary claim.

Researchers will chase micro-details: the angle of the mandibular notch, the contour of the suprainiac fossa, the thickening of cranial vault bones. None of these alone prove ancestry. Together, though, they may hint at interwoven populations moving through the same landscapes, sometimes competing, sometimes partnering, occasionally raising children who carried both legacies.

What the Genes Already Tell Us

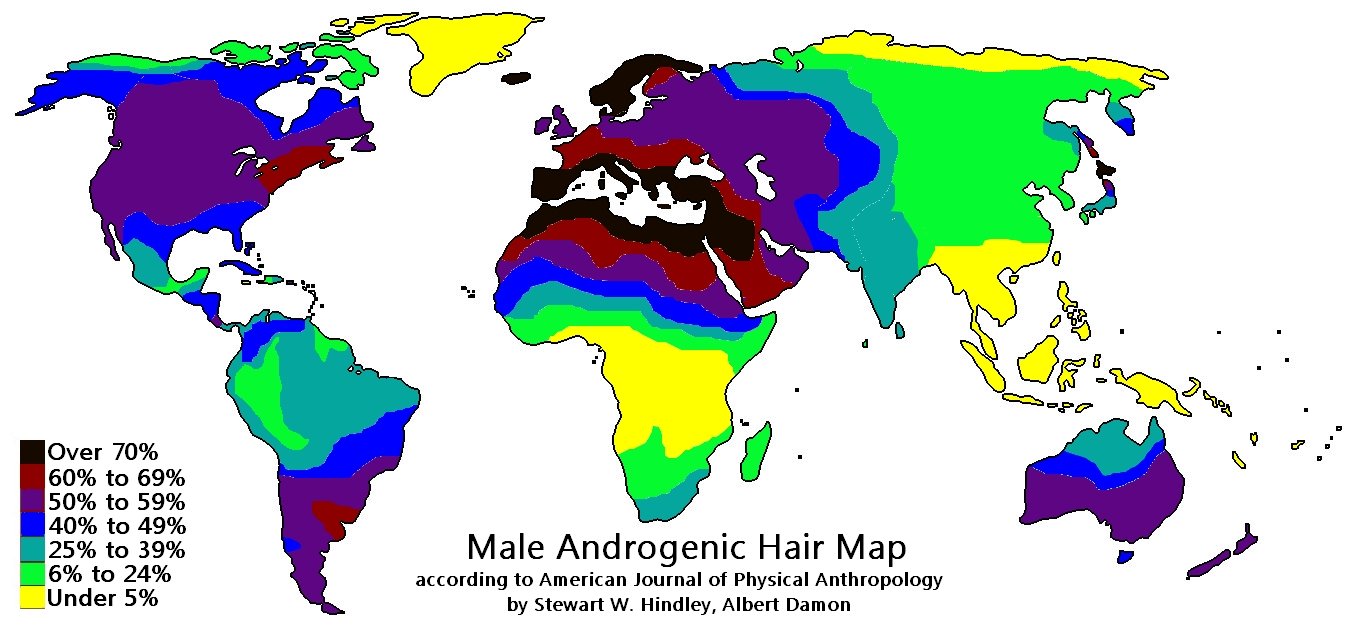

Even if this skull never yields DNA, genetics has already set the stage. People with deep roots outside Africa carry a small but real fraction of Neanderthal ancestry, a genetic signature of ancient contacts. Some early modern individuals from Europe show signs of remarkably recent Neanderthal forebears, measured in only a handful of generations. Meanwhile, populations in Oceania and parts of Asia carry substantial Denisovan ancestry, another branch on our family tree that entwined with ours.

Useful anchors – kept simple, not sensational:

- Neanderthals vanished as a distinct population roughly in the window of forty to forty-five thousand years ago in many regions, as modern humans expanded.

- Ancient individuals in Europe around forty-five thousand years ago sometimes show a very fresh Neanderthal connection, implying overlapping communities.

- A small proportion of Neanderthal-derived variants influence traits today, from immune responses to skin biology.

The Debate Inside the Lab

Hybrid is a sticky word. In paleontology it can imply a first-generation child of parents from different groups, but it’s often misused as shorthand for any mixture of lineages. Without genome data, the label can outrun the evidence, especially if a specimen mixes common traits that merely sit near the edges of normal variation. That’s why most teams now set a high bar: documented context, rigorous dating, and transparent metrics before attaching big claims.

There’s also the practical challenge of sampling. Ancient DNA work is destructive and must be justified, particularly for rare or fragile specimens. Petrous bone can yield more molecules but removing it carries ethical and scientific costs. Good science means weighing what could be learned against what might be lost.

Why It Matters

Stories like this shape how we see ourselves. The idea of contact, exchange, and family between modern humans and Neanderthals pushes back against outdated myths of a clean replacement. It reframes evolution as a braided river rather than a single channel, with eddies, merges, and backflows. For medicine, those ancient exchanges matter because some archaic variants still nudge how our bodies react to pathogens and environments.

There’s a cultural layer too. When we acknowledge that mixing is the rule, not the exception, it undercuts any attempt to weaponize “purity” in human history. The Pleistocene was a crowded neighborhood, and our species learned to live, love, and adapt within it.

Global Perspectives

Europe tends to dominate the conversation, but the bigger map tells a more fascinating story. East Asia shows a different tempo of interactions, with complex waves of migration and local adaptation. In Island Southeast Asia and Oceania, Denisovan-like ancestry hints at encounters far from the European Ice Age dramas we know best. Even within Africa – our species’ cradle – there are signs of deep, structured histories that don’t fit a single tidy narrative.

Put simply, the skull on today’s lab table is one tile in a sprawling mosaic that spans continents. A cautious reading there informs a cautious reading everywhere. The more we compare across regions, the less tempting it becomes to make sweeping claims from one bone, one cave, one moment.

Analysis

Why does this subject matter now? Because the tools that once split Neanderthals and modern humans into separate boxes are giving way to integrative approaches that merge anatomy, archaeology, and genomics. Traditional typology – lining up skulls and scoring traits – was a good start, but it struggled with transitional forms and overlap. Modern approaches reduce bias by quantifying shape, modeling uncertainty, and cross-checking with molecular data.

The likely path forward isn’t a single smoking-gun trait but converging signals. If morphology, stratigraphy, and dating align – and if even a sliver of authentic DNA can be retrieved – then the hybrid hypothesis gains traction. If not, the responsible answer is a measured one: a modern human with archaic affinities, living in a world where neighbors weren’t strangers. Either outcome teaches us something real.

Future Outlook

Expect rapid advances to reshape the debate. Targeted DNA capture, improved contamination controls, and smarter library preparation are rescuing molecules once thought hopeless. Protein sequencing will keep growing as a proxy for genetics when DNA is gone, and sediment DNA is turning cave floors into archives. On the imaging side, ultra-fine CT plus machine learning can tease apart developmental patterns not visible to the naked eye.

Challenges remain. Destructive sampling needs clear ethical frameworks; community partnerships should guide choices about what gets drilled and what stays intact. Funding models must reward careful, negative results as much as headline findings. If we get that balance right, the next skull that sparks debate will also deliver answers grounded in evidence, not wishful thinking.

Conclusion

Stay curious, and support the slow, careful science that separates signal from noise. Visit local museums, read the specimen notes, and support open-access research so data can be checked and reanalyzed. If you’re inclined, back initiatives that train regional labs in ancient DNA and imaging, spreading expertise beyond a handful of centers. Encourage news outlets – and yes, your favorite podcasts – to cover methods, not just claims. What would you look for first if this skull sat in front of you?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.