Long before hard drives, cloud backups, or even bound books, humans were already waging a quiet, brilliant war against oblivion. Ancient civilizations faced a constant threat: every flood, war, or royal whim could erase what a culture had painfully learned. Yet instead of giving in to that fragility, they engineered surprisingly robust systems for capturing, storing, and transmitting information across generations. Today, archaeologists, philologists, and computer scientists are realizing that these early knowledge infrastructures were not primitive prototypes but sophisticated solutions to problems we still struggle with. The story of how our ancestors recorded and preserved knowledge is less a dusty chronicle of ruins and more an ongoing investigation into how humans first learned to outsmart time.

The First Data Engineers: When Clay and Stone Became Memory

It is hard to overstate how radical the invention of writing was for early societies. In Mesopotamia more than five thousand years ago, scribes began pressing wedge-shaped signs into wet clay tablets, not for poetry at first, but to track grain, labor, and debts. This shift from oral memory to external, physical memory turned information into something that could be audited, duplicated, and standardized, much like a modern spreadsheet. The clay itself was a technological choice: durable, abundant, and – once fired – remarkably resistant to fire, decay, and political upheaval.

What looks to us like a box of broken tiles is, in practice, an early database. In cities such as Uruk and later Nineveh, tens of thousands of tablets were stored, cataloged, and sometimes labeled with colophons describing the scribe, the series, and where each text belonged on the shelf. The result was not just record-keeping but an ecosystem of knowledge management, where the physical properties of the medium and the social power of trained scribes combined to keep information coherent over centuries. The fact that many of these tablets survive today, while later papyrus scrolls have mostly vanished, is a testament to how intentionally those early data engineers selected and optimized their storage technology.

Libraries of Power: How Empires Curated Knowledge

Once societies realized that information could be stored outside the human brain, the next step was obvious: collect as much of it as possible. The royal libraries of Assyria, such as the famed collection of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, were not casual hoards of scrolls and tablets but curated repositories with acquisition policies. Officials ordered the copying of older texts from distant cities, gathering everything from medical recipes and astronomical observations to myths and omen series. Knowledge, in this sense, became something that an empire could centralize and monopolize, just as it did grain or metals.

These libraries used surprisingly modern-seeming techniques to manage the chaos of accumulation. Tablets were organized by subject and series, often marked with opening lines, volume numbers, and warnings against stealing or altering them. A royal library was less like a quiet reading room and more like a specialized research center, feeding court astrologers, physicians, and administrators with the texts they needed. When archaeologists rediscovered these archives in the nineteenth century, they were effectively cracking open a time capsule of curated, cross-referenced data that had been deliberately preserved by people who understood its strategic value.

Codes, Calendars, and Control: The Science Inside the Records

Ancient record systems did more than list who owed whom a sack of barley. They became laboratories for pattern detection and predictive reasoning. Babylonian astronomer-scribes, for example, used centuries of recorded planetary observations to identify regularities in celestial motions. On clay tablets, they documented rising and setting times, eclipses, and unusual events, turning the sky into a dataset. Over generations, they developed sophisticated mathematical schemes, including methods resembling early forms of numerical integration, to forecast future positions of planets and lunar eclipses.

Calendars, too, emerged from this marriage of record and prediction. In Mesoamerica, the Maya wove astronomy, ritual cycles, and dynastic history into layered calendrical systems that tracked time across astonishingly long spans. Their Long Count recorded dates across thousands of years, anchored to celestial observations and historical events carved in stone and painted in codices. These were not mere curiosities but tools of political control and ritual timing, allowing rulers to stage ceremonies and wars according to cycles believed to structure the cosmos. Seen today, they look like early interfaces where religion, power, and data science met.

The Hidden Clues in Materials: What Survives and What We’ve Lost

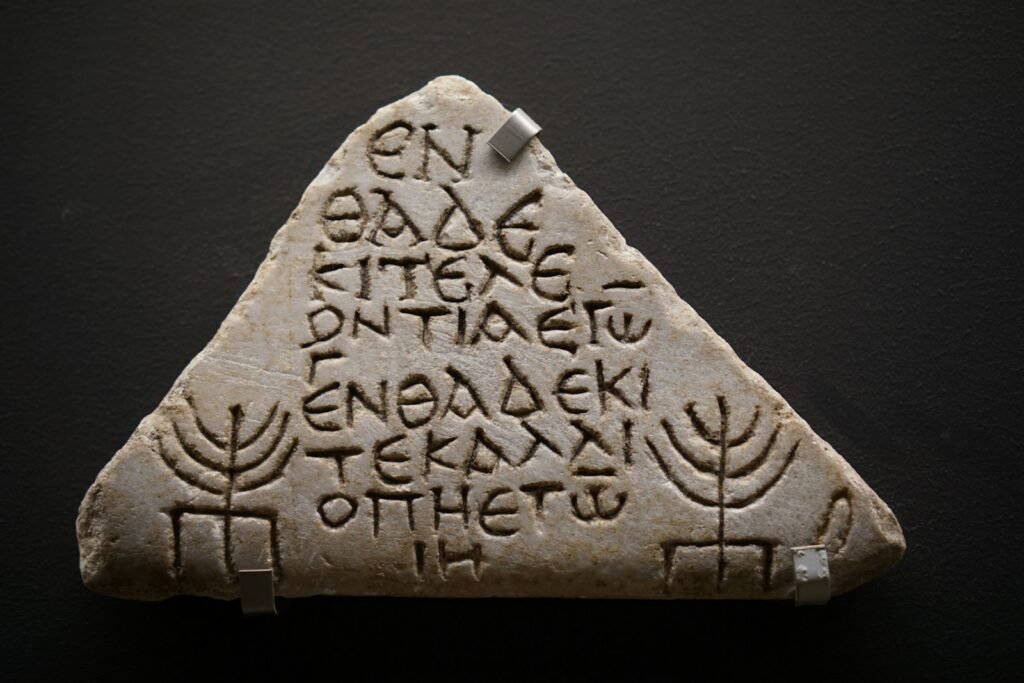

When we talk about ancient knowledge systems, we are really talking about what has survived, and survival is biased by the properties of materials. Clay tablets buried in dry rubble, stone inscriptions cut deep into desert cliffs, and bone or turtle-shell divination records from ancient China have a good chance of enduring thousands of years. By contrast, organic media like palm leaves, bamboo slips, and papyrus scrolls often rot, burn, or are repurposed, silently erasing entire traditions. The result is a skewed archive: some cultures appear to us as extraordinarily literate and data-rich, partly because they happened to write on things that do not easily die.

Yet even within this uneven survival, the choices ancient people made about materials express a clear understanding of durability and audience. Egyptian scribes used stone for monumental inscriptions designed to last for eternity and papyrus for day-to-day administrative work and literary texts that needed to be portable. In early imperial China, bamboo strips and silk manuscripts gave way over time to paper, an innovation that transformed what could be recorded and copied. Archaeologists and materials scientists now study ink composition, carving techniques, and micro-damage to reconstruct not just texts but the workflows of ancient offices, workshops, and temples. Every crack in a tablet or fiber in a scroll is a clue to how seriously people took the problem of making knowledge outlive its makers.

From Oral Epics to Written Canons: Memory as Technology

Writing did not replace human memory overnight; instead, it entered into a complex partnership with oral tradition. Long before epics such as those from the ancient Mediterranean or South Asia were fixed in writing, they lived in the voices of trained performers who used rhythm, formulaic phrases, and narrative structures as mental compression algorithms. These techniques allowed huge story cycles, genealogies, and legal precedents to be stored in living minds, updated in performance, and transmitted with high but not perfect fidelity. When writing finally captured these oral epics, it froze one version of an evolving tradition, effectively turning a flexible memory technology into a canonical reference.

Ancient educators understood that text alone was not enough. In Mesopotamian and Egyptian schools, students copied model texts repeatedly, not just to learn handwriting but to internalize proverbs, laws, and technical lists that would guide their professional lives. In many traditions, recitation and commentary remained central, with written manuscripts acting as anchors rather than substitutes for embodied knowledge. This hybrid model – part oral, part written – resembles modern scientific practice more than we might admit: data lives in databases, but its meaning is negotiated in seminars, labs, and classrooms. The ancients were not naive about this relationship; they designed education systems to keep memory and recording tightly interlinked.

From Clay Tablets to Cloud Servers: Why It Matters

It can be tempting to treat ancient record-keeping as quaint compared with the velocity and volume of data generated today, but the underlying challenges are almost eerily similar. Ancient scribes worried about legibility, loss, and misinterpretation in much the same way archivists and data managers do now. Their solutions – standardized formats, redundancy through copying, and centralized repositories – mirror practices in modern information science. When we design metadata standards or database schemas, we are unknowingly participating in a conversation that began in temple accounting rooms and royal libraries millennia ago.

This continuity matters for at least three reasons. First, it reminds us that information management is a social and political project as much as a technical one; whoever controls archives often shapes what a society remembers as true. Second, studying how different civilizations prioritized what to keep and what to let go offers a mirror for our own digital hoarding, where vast amounts of data are stored with little thought to long-term meaning or accessibility. Third, by examining which ancient systems survived – and which vanished – we gain practical insight into the design of resilient archives for climate-stressed, politically unstable futures. In a sense, ancient civilizations are running an ongoing, multi-millennial stress test on our ideas about what it means to preserve knowledge.

Decoding the Past with Modern Science: New Tools, Old Records

The story does not end with the ink drying or the clay hardening; it continues in the labs and archives where those objects are now being re-read with new technologies. High-resolution imaging, including multispectral and X-ray scanning, has made it possible to recover writing from charred scrolls, faded papyri, and tablets still sealed inside clay envelopes. Machine learning models are being trained to recognize cuneiform signs, reconstruct missing fragments, and even propose joins between broken tablets scattered across multiple museums. What once relied solely on the painstaking eye of a specialist can now be accelerated by pattern-recognition algorithms that see subtle clues humans might miss.

These tools are not replacing traditional scholarship so much as amplifying it. For example, computational linguistics allows researchers to map how certain formulae, legal clauses, or astronomical terms spread across regions and centuries, revealing networks of intellectual exchange. Materials analysis, from isotope studies of parchment to pigment composition in inks, links manuscripts to specific landscapes and trade routes. Together, these approaches are turning ancient archives into rich datasets for asking new kinds of questions about how ideas move, adapt, and sometimes disappear. The result is that ancient knowledge systems are being pulled into the broader field of data science, not as curiosities, but as complex information infrastructures worthy of rigorous analysis.

Future Archives: Lessons for a Planet Drowning in Data

As we race deeper into the digital age, the most unsettling parallel with the ancient world is not scarcity of information but its fragility. Hard drives fail, formats become obsolete, and servers depend on political and economic stability that history suggests is rarely permanent. Looking back, the durability of a fired tablet or a carved stone stela starts to feel less quaint and more like a serious engineering benchmark. Some researchers are already exploring ultra-stable storage media, from etched quartz glass to DNA-based archives, explicitly inspired by the time scales over which ancient records have survived.

The challenges ahead are not just technical. Just as ancient elites decided which rituals, laws, and stories deserved stone, we now face choices about which digital records merit the most resilient preservation. Climate change, rising seas, and conflict threaten physical archives and data centers alike, forcing conversations about distributing backups across continents and even off-world storage. At the same time, concerns about surveillance, privacy, and cultural ownership complicate any simple push to preserve everything forever. The deeper lesson from ancient civilizations may be that a robust knowledge system balances redundancy with selectivity, durability with adaptability – a balance we are only beginning to think about at planetary scale.

How You Can Help Keep Knowledge Alive

The machinery of large-scale knowledge preservation can feel remote, tucked away in national archives, university basements, and server farms. Yet individual choices still matter in shaping what the future can know about us. Supporting local museums, libraries, and community archives helps protect fragile collections of letters, recordings, and photographs that may never make headlines but are essential threads in the larger human story. Even small acts – labeling family photos with names and dates, backing up important digital files in open formats, or donating time to transcription projects – add resilience to the collective record.

For those drawn to the intersection of history and science, there are accessible ways to engage with the reconstruction of ancient knowledge systems. Online platforms invite volunteers to help decipher old manuscripts, tag images of tablets and inscriptions, or proofread transcriptions that feed into open databases used by researchers worldwide. Educators can weave discussions of ancient information management into lessons about data literacy, drawing a line from clay tablets to social media feeds. In doing so, we acknowledge that preserving knowledge is not just an expert task but a shared civic responsibility that stretches from the first scribes to anyone who hits save today.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.