The idea sounds like science fiction: a distant star explodes, and millions of years later, life in Earth’s oceans and on land subtly changes course because of it. Yet over the last decade, a convergence of astrophysics, geology, and biology has turned that wild notion into a serious scientific discussion. Radioactive fingerprints in deep‑sea rocks, new models of cosmic radiation, and fresh looks at Earth’s evolutionary record all point toward a surprising possibility. A nearby supernova or even a series of them may have bathed our planet in high‑energy particles, nudging climate, extinction, and evolution in ways we are only just starting to trace.

Stellar Catastrophe on Our Cosmic Doorstep

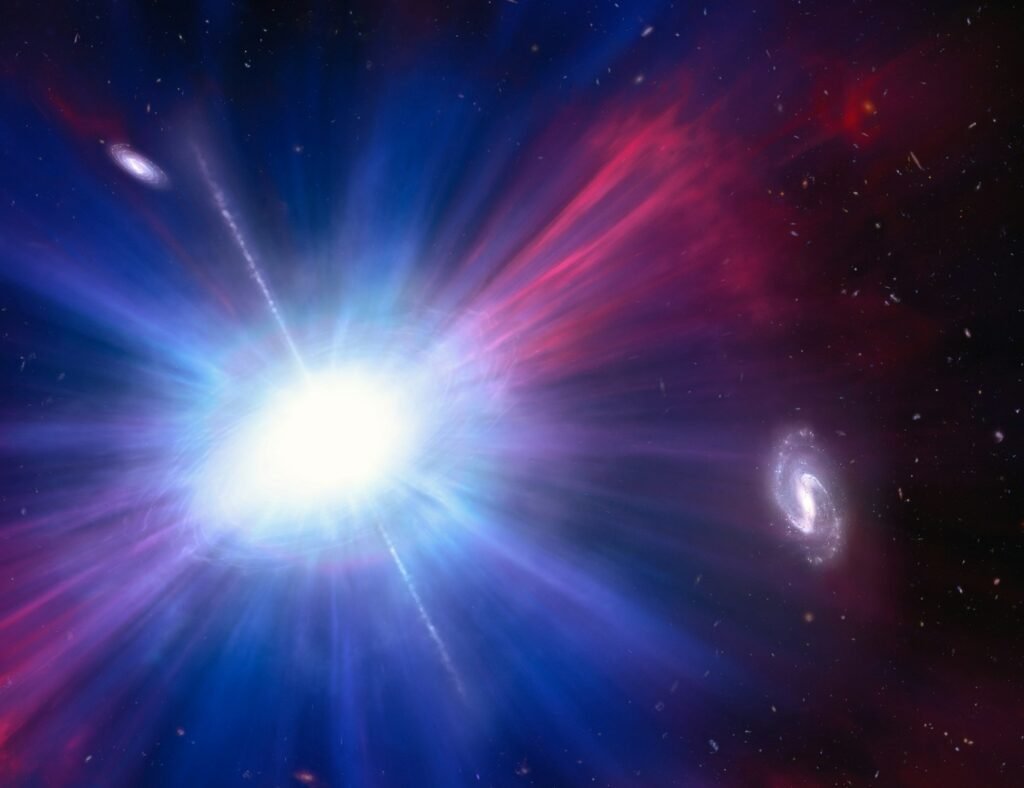

For most of human history, a supernova was just a strange new star in the sky, an omen more than a physical event. Astrophysics has transformed that picture, revealing supernovae as colossal detonations that occur when massive stars run out of nuclear fuel and collapse or when compact stellar corpses collide. In a fraction of a second, they release more energy than our Sun will emit in its entire multi‑billion‑year lifetime, hurling matter and radiation across space at nearly unimaginable speeds.

Most of these cataclysms are so far away that their effects on Earth amount to little more than a pretty light show for telescopes. But the Milky Way is not a quiet neighborhood, and the Sun orbits within a dynamic galactic environment threaded with star‑forming regions and aging, unstable giants. When a massive star explodes within a few hundred light‑years, the expanding blast wave and its stream of high‑energy particles can eventually sweep over our solar system, potentially disturbing Earth’s protective magnetic bubble and atmosphere.

Iron Clues Buried in Ancient Ocean Sediments

The case for a real supernova impact on Earth’s history rests on one particularly telling piece of forensic evidence: radioactive iron‑60. This rare isotope is not produced in significant quantities on Earth today and decays over a timescale of a few million years, which means any iron‑60 present when our planet formed has long since vanished. When researchers began finding traces of iron‑60 in deep‑sea crusts and sediments, it was like discovering alien ash in the fossil record.

Independent teams analyzing samples from different oceans have reported iron‑60 layers dating back roughly between about two and eight million years ago, with peaks that seem to cluster in specific intervals. Those layers line up suspiciously well with the timeframe in which the Sun was likely passing near a group of massive stars in what astronomers call the Local Bubble, a cavity in the interstellar medium carved by multiple ancient supernovae. The simplest explanation many scientists now consider is that one or more nearby supernovae dusted Earth with iron‑60, which later settled into the ocean floor and became locked in mineral layers we can read today.

How Cosmic Rays Can Reshape an Atmosphere

A supernova’s danger to life on Earth does not come from a visible flash across the sky but from the invisible hail of high‑energy particles known as cosmic rays. When a supernova occurs close enough, its cosmic‑ray front can arrive at Earth tens of thousands of years later and persist for hundreds of thousands of years as particles scatter and diffuse through space. When those particles slam into our upper atmosphere, they trigger showers of secondary particles and chemical reactions that can alter the balance of key gases.

Models suggest that an elevated cosmic‑ray flux from a nearby supernova could thin the ozone layer, especially at high latitudes, allowing more ultraviolet radiation from the Sun to reach the surface. Increased ionization in the lower atmosphere may also influence cloud formation, potentially changing regional climate patterns over long timescales. None of this looks like an instant, cinematic extinction; it is more akin to turning up multiple environmental dials by a small but persistent amount, the kind of changes that can pressure ecosystems and steer evolutionary paths.

Marine Faunas, Extinction Ripples, and Evolutionary Twists

If a supernova did tweak Earth’s radiation environment a few million years ago, the key question is whether we can see its fingerprints in the biological record. Some paleontologists have pointed to shifts in marine biodiversity around the end of the Pliocene, when certain lineages declined while others radiated into new niches. The idea is that increased ultraviolet exposure might have been especially hard on surface‑dwelling plankton and larvae, which form the foundation of many ocean food webs and are sensitive to subtle environmental stress.

There are also discussions around patterns of extinction and turnover in coastal and shallow‑water ecosystems that roughly coincide with iron‑60 layers. The story is not straightforward, because climate, tectonics, and ocean circulation were also changing at the time and surely played major roles. Still, the possibility that altered atmospheric chemistry and radiation levels from a nearby supernova amplified other environmental pressures is attracting more attention. Rather than a single killer blow, researchers are exploring whether cosmic events can act as background sculptors, slowly reshaping which species thrive and which fade away.

The Local Bubble: A Galactic Crime Scene

To trace the origin of the iron‑60 and the suspected cosmic‑ray surge, astronomers have turned the Milky Way into a kind of three‑dimensional crime scene map. Observations show that the Sun currently sits inside the Local Bubble, an unusually hot, low‑density cavity about a thousand light‑years across that appears to have been carved out by multiple supernova explosions. By combining stellar motions, ages of nearby star clusters, and gas distribution maps, researchers have reconstructed where those explosions likely occurred and when.

These reconstructions suggest that a moving cluster of stars now about several hundred light‑years away, sometimes linked to associations such as Scorpius–Centaurus, may have passed much closer to our solar system in the past. As the most massive stars in that cluster reached the ends of their lives, they would have exploded in a sequence of supernovae, inflating and maintaining the Local Bubble. In this reconstruction, Earth was not a distant spectator; it was inside the growing bubble, periodically swept by waves of energetic particles and enriched dust. The timing of some of those events lines up intriguingly with the iron‑60 anomalies and with important transitions in Earth’s climate and biota.

What Makes a Supernova Truly Dangerous to Life

Astrophysicists have long debated how close a supernova needs to be to pose a serious threat to complex life. Current estimates usually place the most catastrophic range at within a few tens of light‑years, where intense radiation could severely damage the ozone layer and directly irradiate the surface. The suspected supernovae associated with the iron‑60 findings were likely farther away, on the order of a hundred light‑years or a bit more, putting them in a kind of intermediate hazard zone. That distance is too far for a mass‑extinction‑level catastrophe, but close enough to plausibly drive long‑term atmospheric and climatic changes.

One underappreciated factor is Earth’s own shielding system: the geomagnetic field and thick atmosphere together act as a planetary shock absorber. Variations in magnetic field strength and configuration over geologic time could have made some epochs more vulnerable than others to incoming cosmic rays. This means that whether a given supernova is disastrous or merely influential depends not only on its distance and energy, but also on the state of Earth’s protective layers at the time. Our planet’s history with supernovae is therefore likely a spectrum of outcomes, from barely noticeable to potentially transformative.

Rewriting Evolutionary Narratives: Beyond Earth‑Only Explanations

The deeper significance of this research lies in how it expands our sense of what shapes life on Earth. For decades, standard evolutionary narratives have focused on familiar drivers: mutation, natural selection, climate change, plate tectonics, and chance. The growing evidence for supernova influences does not displace those factors, but it adds an extra tier of causation that originates tens or hundreds of light‑years away. Evolutionary biology traditionally treated cosmic events as rare, distant catastrophes, yet the new picture hints at a more continuous conversation between Earth and its galactic environment.

Comparing this emerging view with older models is a bit like moving from a local weather report to a full planetary climate system map. Previously, many discussions of extinction events invoked only volcanic eruptions or asteroid impacts for external triggers. Now, nearby supernovae are joining that shortlist, not always as primary culprits, but as credible co‑conspirators that might modulate background radiation and climate over millions of years. This pushes both astrophysics and evolutionary science into a more integrated framework, where the Milky Way itself becomes part of the story of life, instead of just a pretty backdrop.

Unanswered Questions at the Edge of Evidence

Despite the excitement, the supernova–evolution link is far from a closed case, and that uncertainty is part of what makes it scientifically compelling. Iron‑60 layers provide strong circumstantial evidence for nearby supernovae, but connecting them directly to specific biological events remains difficult. The fossil record is patchy, and dating layers with the precision needed to match astrophysical timelines is challenging. Climate records from ice cores, sediments, and fossils also come with uncertainties that make it hard to disentangle overlapping causes.

Researchers are now hunting for additional isotopic markers, such as rare forms of plutonium, and for more finely resolved iron‑60 records in different parts of the world’s oceans. They are refining cosmic‑ray and atmospheric models to better predict what a supernova “signature” would look like in paleoclimate data and evolutionary trends. As these lines of evidence tighten, some proposed links may fall apart while others grow more persuasive. For now, the debate is a reminder that science progresses not by instant consensus, but by testing bold ideas against stubborn rocks and fossils.

How Curious Earthlings Can Join the Galactic Investigation

It might seem that the role of distant supernovae in Earth’s evolution is a topic reserved for specialists, but there are practical ways for curious readers to engage. Public data from space observatories, cosmic‑ray detectors, and geological surveys are increasingly accessible, and citizen‑science platforms sometimes host projects related to stellar mapping or variable stars. Following how these datasets get stitched together into a coherent story can sharpen anyone’s understanding of how evidence accumulates in modern science. Even something as simple as learning the basics of stellar life cycles can make night‑sky observing feel more like reading history than just stargazing.

On a more reflective level, the emerging connection between deep space and deep time is a powerful antidote to a narrow, Earth‑only perspective. Recognizing that living things here may have been nudged by explosions light‑years away invites a kind of cosmic humility and curiosity at the same time. It encourages support for observatories, geological research programs, and science education that keep these cross‑disciplinary connections alive. And it leaves a lingering, provocative thought: the next time you see a bright star in the sky, how might its eventual death ripple through the story of life on this small, blue world?

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.