Imagine waking up to headlines claiming that compasses now point south, satellites are glitching, and airlines are rerouting flights across the globe. It sounds like a sci‑fi disaster movie, but it is actually rooted in a real phenomenon that has happened many times in Earth’s history: magnetic field reversals. The idea that north could suddenly become south is both thrilling and unsettling, and it immediately raises a nervous question: would life on Earth be in danger?

In reality, the story is more complicated, more subtle, and in some ways more fascinating than the dramatic scenarios we usually see in movies. A magnetic reversal would definitely matter for our technology and for how we navigate, but it is not the instant extinction button many people imagine. To really understand what might happen, we have to dig under our feet, into Earth’s core, and then look all the way up into space, where our planet’s invisible magnetic shield is constantly wrestling with the solar wind.

How Earth’s Magnetic Field Actually Works

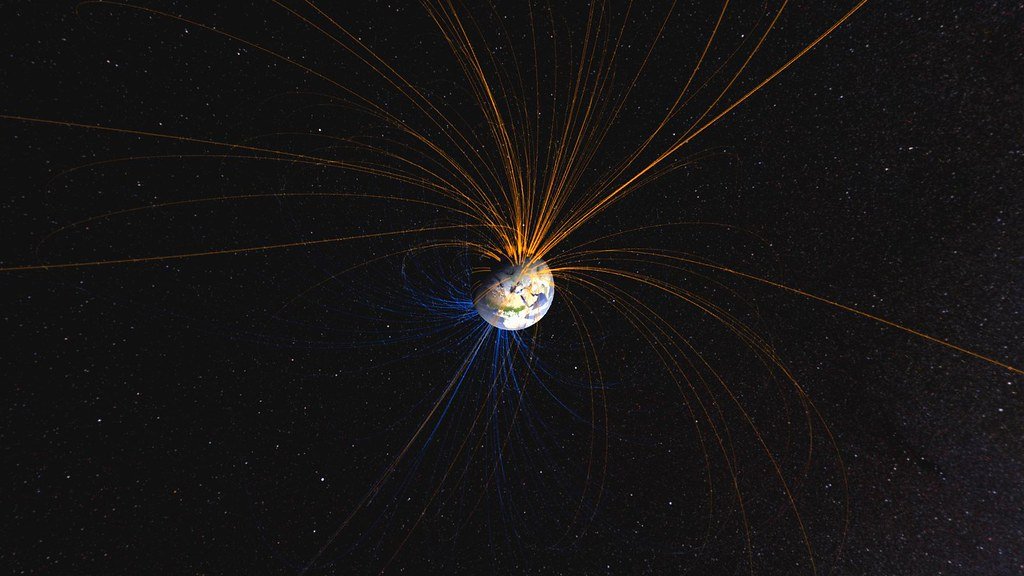

Most of us grow up thinking of Earth’s magnetic field as something simple, like a bar magnet buried under the North Pole, but the reality is far messier and more alive. The field is generated deep inside the planet, in the outer core, where liquid iron and nickel swirl around like a slow-motion metallic ocean. These moving, electrically conducting fluids create electric currents, which in turn generate the magnetic field through what physicists call a geodynamo. It is less like a solid magnet and more like a constantly churning power plant under our feet.

Because this system is driven by chaotic flows of molten metal, the field is never fully stable. It shifts, drifts, and wobbles, and the magnetic poles wander across the surface over time, sometimes moving dozens of kilometers in a single year. The field is also not a perfect dipole with a neat north and south; it has lumps, weak spots, and complex regions where the field lines bend and twist in odd ways. When people imagine a sudden reversal, they often picture a clean snap, but the underlying machinery is much more like turbulent weather than a simple switch.

Magnetic Reversals: They’ve Happened Many Times Before

One of the most surprising facts is that Earth’s magnetic field has flipped many, many times in the past. Geologists have pieced this together by studying volcanic rocks and sediments on the seafloor, which lock in the direction of the magnetic field as they cool or settle. These rocks show long stretches of normal polarity, where north is roughly where it is today, interrupted by periods where the polarity is reversed and a compass would point the other way. This pattern, called the geomagnetic polarity timescale, stretches back hundreds of millions of years.

On average, full reversals seem to happen roughly every few hundred thousand years, but that “average” is wildly unreliable. Sometimes the field goes millions of years without flipping; other times reversals cluster more closely. What we do not see, though, is any consistent link between reversals and mass extinctions or global biological crises. Life has sailed through these flips over and over again, from ancient microbes to dinosaurs to mammals. That alone should calm some of the more apocalyptic fears and remind us that a reversal is disruptive, but not necessarily catastrophic for life itself.

Would It Really Be “Sudden”? What the Timescale Looks Like

When people hear that the field could “suddenly” reverse, it is easy to imagine it happening overnight, like some cosmic light switch. In reality, every line of evidence we have suggests reversals are slow by human standards, unfolding over thousands of years. During that time, the field becomes more disorganized and weaker overall, with multiple north and south poles popping up in different locations. Instead of a clean flip, you get a messy, confused field that gradually stabilizes into the opposite orientation. It is more like watching a storm system rearrange itself than hitting a button.

Even the fastest known magnetic changes in the geological record still take much longer than a human lifetime. This means no one generation would likely experience the entire process from start to finish, just a slice of it. The real concern is not a single day when everything breaks, but a drawn‑out period where the field is weaker and patchier, and technology built for a strong, stable field starts to run into trouble. So when we say “sudden” in geophysics, we are really talking about “fast” on the scale of continents and deep time, not the daily rhythms of human life.

Radiation, Ozone, and the Risk to Life on Earth

One of the biggest fears people have is that a weaker magnetic field during a reversal would let in dangerous cosmic radiation and fry life on the surface. It is true that the field helps shield us from charged particles streaming from the Sun and from deep space, and if that shield weakens, more of those particles can reach the upper atmosphere. That can lead to increased production of chemically reactive molecules that can nibble away at the ozone layer, the thin shield that blocks much of the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation. A weaker field could therefore mean more stress on the atmosphere, especially during strong solar storms.

But here is the key point: even when the magnetic field weakens significantly, it does not vanish entirely, and our atmosphere itself is still a major protective barrier. Geological and biological records do not show a pattern of mass die‑offs linked to geomagnetic reversals, even over hundreds of millions of years. Some increased radiation at high altitudes and polar regions is likely, and that could affect frequent fliers, astronauts, and high‑latitude ecosystems more than others. Still, for most people and most forms of life at Earth’s surface, a reversal looks less like an instant death sentence and more like an extra environmental stress layered on top of everything else we are already dealing with.

Satellites, Power Grids, and the Technology Problem

Where a magnetic reversal really starts to bite is in our technology, especially in space. Satellites orbit in a region where Earth’s protective bubble, the magnetosphere, interacts directly with the solar wind. When the magnetic field weakens or becomes more irregular, satellites can be exposed to more charged particles, which can damage electronics, degrade solar panels, and interfere with communications. Even today, with a fairly strong field, big solar storms occasionally knock out satellites or disrupt GPS signals; during a prolonged weakened‑field phase, those risks climb significantly.

On the ground, changing magnetic conditions can induce currents in long power lines and pipelines, a bit like wiggling a magnet near a wire to create electricity. Strong geomagnetic disturbances have already caused serious problems, such as large power outages in the past during intense solar storms. In a world where the field is less stable, grid operators might have to treat space weather like we currently treat hurricanes: something you actively plan for, model, and prepare backup systems around. None of this is unmanageable, but it would demand serious investment, smarter infrastructure, and the humility to admit that our technology is still very much at the mercy of space and the deep Earth.

Navigation, Animals, and Everyday Human Life

A magnetic flip would also scramble one of humanity’s oldest tools: the compass. Traditional compasses would slowly become less reliable as the field grew more chaotic, and navigation charts based on magnetic north would need constant updates. In practice, though, much of our modern navigation depends on GPS and inertial systems rather than a simple needle in a box. Pilots, sailors, and emergency services already adjust for magnetic field changes, because the poles wander even today. A reversal would make that process more frequent and complex, but not impossible to manage.

More intriguingly, many animals rely on the magnetic field to find their way. Birds, sea turtles, salmon, and even some insects appear to have some form of magnetic sense, like a built‑in invisible map and compass. During a reversal, their navigation cues might become patchy or misleading, which could disrupt migrations or breeding patterns. Yet the fossil record suggests that life has coped with this challenge many times before. Species may adapt, adjust their behaviors, or rely more on other senses like smell, stars, or landmarks. Everyday human life, outside of specialized professions and certain regions, would likely notice the reversal more in the news and in policy debates than in daily routines like commuting or going to the grocery store.

Are We Headed Toward a Reversal Now?

It is natural to wonder whether we are on the brink of one of these events right now. Scientists track changes in Earth’s magnetic field through ground observatories, satellite missions, and measurements of how the field drifts year by year. Over the last couple of centuries, the overall strength of the field has decreased by a noticeable amount, and areas like the South Atlantic Anomaly, where the field is unusually weak, have grown and shifted. These patterns have sparked speculation that we might be entering the early stages of a reversal or at least a significant reorganization of the field.

However, the magnetic field has gone through ups, downs, and weird patches many times without ending in a full flip. A weakening field can be part of normal variations, a bit like how a stormy season does not always lead to a hurricane. At our current level of understanding, we cannot confidently predict the timing of the next reversal, whether it is thousands of years away or much further in the future. What we can say is that changes are ongoing, they matter for modern technology, and they are worth paying attention to without slipping into panic. In a sense, watching the field evolve is like watching the heartbeat of the planet’s core, a reminder that Earth is still very much alive inside.

Conclusion: A Dramatic Shift, But Not the End of the World

If Earth’s magnetic field suddenly reversed in the geological sense, the most dramatic effects would not be fire raining from the sky, but a long, messy period of adjustment for our technology and our infrastructure. Life on Earth has already survived countless flips, but our satellites, power grids, and navigation systems have never had to face one, and they would become the real front line of impact. A weaker, more chaotic field would mean more vulnerability to solar storms, more stress on high‑altitude and polar regions, and a new set of engineering problems we would have to take seriously.

At the same time, the idea of a reversal is a humbling reminder that our planet is dynamic and that human civilization is layered over processes we do not control. Instead of treating a future flip as an unstoppable apocalypse, it makes more sense to see it as a challenging but manageable test of our ability to plan ahead, adapt, and build resilient systems. The magnetic field has been flipping for hundreds of millions of years; we are the first species to understand what that means and to prepare for it. Knowing that, how differently do you look at a simple compass pointing north?