Look up at a clear night sky and you are staring at hundreds of billions of stars. Statistically speaking, the odds of us being the only intelligent life in all that vastness seem laughably small. So where is everyone? That is the question that has quietly haunted physicists, astronomers, and philosophers for decades.

The universe has been cooking for nearly 14 billion years. That is a staggering amount of time for life to develop, evolve, and eventually discover radio telescopes, rocketry, and the concept of interstellar travel. Yet silence. Total, unbroken cosmic silence. The theory known as the Great Filter offers one of the most compelling, and most unsettling, explanations for why our skies remain empty. Let’s dive in.

The Fermi Paradox: The Question That Started Everything

Picture yourself sitting at a lunch table in 1950 with some of the greatest minds in physics. That is essentially the setting when Nobel laureate Enrico Fermi reportedly looked up mid-conversation and asked a deceptively simple question. That famous phrase, “Where is everybody?” perfectly encapsulated what has since become known as the Fermi paradox: if life happened here on Earth and the universe tends not to do things only once, then life should also occur elsewhere.

With an almost unfathomable number of stars and planets in the universe, it seemed obvious that intelligent civilizations capable of developing radio astronomy and interstellar travel should speckle the distant stars. Yet in Fermi’s day, no evidence of such civilizations existed, something that still holds true today. Think about that for a second. We have launched probes, pointed radio telescopes at millions of stars, and scanned the sky for decades. Nothing.

Enter Robin Hanson: The Great Filter Is Born

Economist Robin Hanson first proposed the Great Filter in the late 1990s. It is the idea that, even if life forms abundantly in our Milky Way galaxy, each extraterrestrial civilization ultimately faces some barrier to its own survival. What makes this theory genuinely fascinating is that it was not a physicist or an astronomer who formalized it. It was an economist thinking in terms of probabilities and bottlenecks, which honestly might be exactly the kind of mind this problem needed.

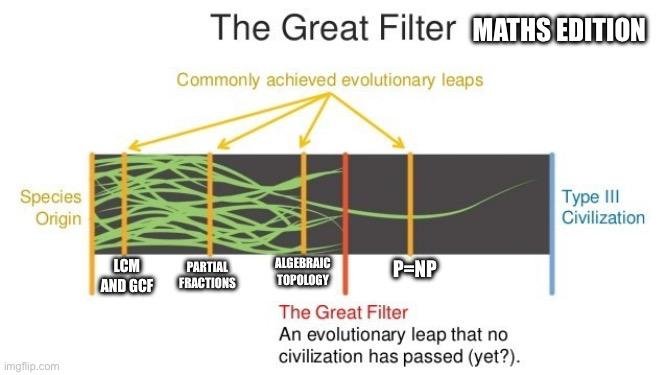

Simply stated, the Great Filter says that intelligent interstellar lifeforms must first take many critical steps, and at least one of these steps must be highly improbable. The premise is that there is at least one hurdle so high that virtually no species can clear it and move on to the next. It is a bit like a cosmic obstacle course where most competitors fall at the same fence, but nobody is there to see it happen.

The Nine Steps: A Ladder Few Can Climb

In his essay, Hanson argued that the filter must lie somewhere between the point where life emerges on a planet and the point where it becomes an interplanetary or interstellar civilization. Using life on Earth and the emergence of humanity as a template, Hanson outlined a nine-step process that life would need to follow to reach the point of becoming a spacefaring civilization. These steps include everything from finding the right star system with habitable planets, to developing reproductive molecules, complex cells, multicellular organisms, and eventually technology capable of interstellar travel.

According to the Great Filter hypothesis, at least one of these steps must be improbable. If it is not an early step in the past, then the implication is that the improbable step lies in the future and humanity’s prospects of reaching interstellar colonization are still bleak. If the past steps are likely, then many civilizations would have developed to the current level of the human species. Here is the thing though: none of them seem to have made it all the way. That is what keeps scientists up at night.

Abiogenesis: Was the Spark of Life Itself the Filter?

The most commonly agreed-upon low probability event is abiogenesis: a gradual process of increasing complexity of the first self-replicating molecules by a randomly occurring chemical process. Honestly, when you think about it, the leap from inert chemistry to a self-replicating molecule is staggering. It is roughly like expecting a tornado to sweep through a junkyard and accidentally assemble a functioning aircraft. Not impossible. Just extraordinarily unlikely.

On Earth, this occurred relatively quickly after the planet cooled, roughly 4 billion years ago. The rapid appearance of life on Earth might suggest this step is easy. However, scientists have not yet managed to replicate this process in a laboratory setting from scratch. That failure to reproduce it tells us something important. We know it happened here. We just have no idea how improbable it truly was. And that uncertainty is exactly what makes abiogenesis such a powerful candidate for the Great Filter.

The Eukaryotic Leap and the Rarity of Complex Life

On Earth, prokaryotes dominated for billions of years before the first eukaryotes appeared, cells with a nucleus, which became the basis for developing multicellular organisms. The transition from single-celled to multicellular organisms is another complex stage of evolution, requiring the development of mechanisms of cellular specialization and cooperation. Earth saw this transition only once, and scientists still do not fully understand how and why it happened.

Perhaps it is common for life to spontaneously arise, but the overwhelming majority of life never progresses beyond simple single-cell organisms. Maybe the universe is teeming with bacteria, but bacteria don’t build starships. That image is both humbling and strangely funny. A cosmos full of microbial passengers who never quite made it to the driver’s seat. Other proposed great filters include the emergence of eukaryotic cells or of meiosis, or some of the steps involved in the evolution of a brain-like organ capable of complex logical deductions.

The Intelligence Problem: Rare by Design

As for the appearance of intelligence, we know that our kind of intelligence emerged only once in the history of life on Earth and that it took billions of years to show up. From this one solitary data point, it seems that simple life may be common, but intelligence is rare. So maybe that is the filter: it is just hard to evolve intelligent beings. That conclusion carries weight. Billions of species have lived and died on Earth. Only one ever looked up and started asking questions about the stars.

Among the millions of animal species on Earth, only one, the human being, has a developed intellect capable of abstract thinking, language, and the creation of complex technologies. Perhaps the emergence of intelligent life is an exceptional event, and not a natural stage of evolution. I find this perspective sobering rather than discouraging, because it reframes intelligence not as the expected destination of evolution but as a wildly lucky accident. One that may not have repeated anywhere else in the observable universe.

The Future Filter: Could We Be Our Own Worst Enemy?

Some researchers posit that the most plausible future filter is self-destruction. Three commonly discussed self-destruction scenarios include nuclear war, excessive global warming, and conflict with or domination by artificial intelligence. This is where the Great Filter stops being a philosophical puzzle and starts feeling uncomfortably personal. We are a species that invented nuclear weapons within decades of discovering electricity. That is not a reassuring track record.

In a recent paper, Michael Garrett, Sir Bernard Lovell Chair of Astrophysics at the University of Manchester and Director of the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, outlines how the emergence of artificial intelligence could lead to the destruction of alien civilizations. Garrett has suggested that biological civilizations may universally underestimate the speed at which AI systems progress and not react to it in time, thus making it a possible Great Filter. He also argues that this could make the longevity of advanced technological civilizations less than 200 years, explaining the great silence observed by SETI. That is a chillingly short window.

Behind Us or Ahead of Us: The Most Important Question in Science

The first major possibility is that the Great Filter lies in our past. This is the optimistic interpretation for human survival, though it implies a lonely existence. It suggests that one of the early evolutionary steps, such as abiogenesis or the development of the eukaryotic cell, is astronomically difficult to achieve. If the filter is behind us, we are essentially the cosmic lottery winners. Rare, remarkable, and maybe completely alone.

Oxford University philosopher Nick Bostrom says that “no news is good news.” The discovery of even simple life on Mars would be devastating, because it would cut out a number of potential Great Filters behind us. If we were to find fossilized complex life on Mars, Bostrom says it would be by far the worst news ever printed on a newspaper cover, because it would mean the Great Filter is almost definitely ahead of us, ultimately dooming the species. That perspective reframes Mars exploration in a way that is hard to shake. Finding life out there might not be a triumph. It might be a warning.

Conclusion: The Silence Speaks Volumes

The Great Filter is one of those ideas that, once you truly understand it, changes how you look at the night sky. The main conclusion of the Great Filter is that there is an inverse correlation between the probability that other life could evolve to the present stage in which humanity is, and the chances of humanity to survive in the future. In other words, the luckier we have already been, the luckier we still need to be.

Whether the filter is somewhere buried in our distant evolutionary past or looming just ahead of us in the form of AI, climate collapse, or some catastrophe we have not yet imagined, the theory forces an uncomfortable reckoning. Researchers advocate for proactive global policies and technological strategies to mitigate risks and secure humanity’s path beyond the Great Filter. We are not passengers in this story. We are the ones writing it, with very high stakes and no second draft. The cosmic silence is not just eerie. It might be the universe’s way of telling us something profound. The real question is: are we listening?