We like to imagine evolution as a clean ladder: single-celled blobs gradually turning into fish, then lizards, then monkeys, then finally us at the top, arms folded in triumph. It feels neat, almost comforting. But the more scientists uncover about life’s history, the more that tidy ladder collapses into something wilder, messier, and honestly, far more fascinating.

Evolution is not a straight road with a finish line; it’s a tangled, branching, looping network of dead ends, comebacks, shortcuts, and bizarre experiments. Once you see that, the story of life stops being a simple progress narrative and starts looking more like an epic, with plot twists you’d never expect. Let’s walk through some of the strangest turns in the tree of life and see why the truth is way more surprising than the myths.

The Myth of the Ladder: Why “Higher” and “Lower” Life Is Misleading

Have you ever heard someone say humans are “more evolved” than other animals? That idea is one of the stickiest and most misleading myths in biology. Evolution doesn’t have an end goal, and it certainly isn’t trying to produce big-brained primates as its ultimate masterpiece. Every living species today has been evolving for roughly the same amount of time, each adapting to its own challenges and environment.

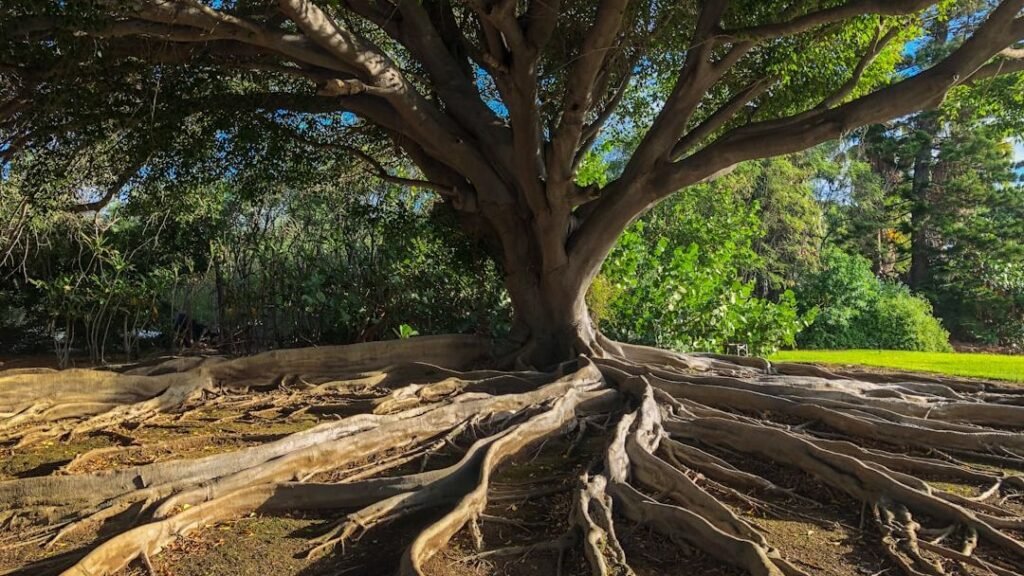

If evolution were a ladder, you’d expect a clear path from “simple” to “complex.” Instead, what we see is a branching tree, where bacteria, oak trees, beetles, and whales are all at the tips of their own twigs. A jellyfish isn’t “behind” a human on some cosmic scale; it’s just on a different branch that took a different route. When you stop thinking in terms of higher and lower, it suddenly makes more sense that fungi can outcompete us in some ecosystems, or that bacteria can outsmart our best antibiotics in just a few years.

Life’s First Big Twist: We’re All Chimeras of Ancient Microbes

One of the most shocking discoveries in evolutionary biology is that complex life, including humans, may have started with a kind of microbial merger. Our cells are not just descendants of one ancestral microbe; they carry the legacy of at least two different lineages that joined forces billions of years ago. The tiny energy factories inside our cells, mitochondria, were once free-living bacteria that moved in rather than being digested.

This event, known as endosymbiosis, was less like a step on a ladder and more like two branches fusing together. Plants added another twist by acquiring chloroplasts, which began as separate photosynthetic bacteria. So when you look at a tree, a mushroom, or your own hand, you’re really looking at the outcome of ancient collaborations. Life didn’t climb steadily upward; it hacked the system by merging technologies that evolved separately in different organisms.

Convergent Evolution: When Nature Re-Invents the Same Tricks

One of my favorite plot twists in evolution is convergent evolution, where totally unrelated creatures independently evolve almost the same solution to a problem. Think of it like different inventors on opposite sides of the world coming up with nearly identical gadgets without ever meeting. Dolphins and ichthyosaurs (extinct marine reptiles) both ended up with streamlined bodies, flippers, and tail fins, even though one is a mammal and the other was a reptile from the age of dinosaurs.

Wings are another classic example: insects, birds, and bats each evolved the power of flight through completely separate paths. Even eyes, which seem too complex to have appeared more than once, have evolved multiple times in different forms across animals. These repeated patterns show that evolution doesn’t move in a straight line, but some paths are so useful that life stumbles onto them again and again. It’s less like a scripted story and more like a game where certain moves keep reappearing because they work so well.

Evolutionary U-Turns: When “Losing” Traits Is Actually Winning

We tend to assume evolution always adds things: more bones, more complexity, more brain power. But sometimes the smartest evolutionary move is to throw things away. Cave fish that live in total darkness have lost their eyes over many generations, because maintaining eyes in a pitch-black cave wastes precious energy. There are birds that have lost the ability to fly because they do better running on the ground, especially on islands where predators are scarce.

Even humans show hints of evolutionary subtraction. Our jaws are smaller than those of many of our ancestors, and wisdom teeth often cause problems because our skulls no longer fully “fit” them. Some animals have lost limbs, like snakes that descended from four-legged lizards but gradually evolved a limbless body better suited for burrowing and slithering. These reversals make it clear that evolution isn’t obsessed with complexity; it is obsessed with whatever works in the moment, even if that means simplifying or giving up once-useful features.

Horizontal Gene Transfer: Evolution’s Secret Shortcut

If you imagine your family tree as a clean branching pattern, horizontal gene transfer is like drawing weird sideways arrows between distant branches. This phenomenon, especially common in bacteria, allows genes to jump from one species to another without reproduction. That’s part of why antibiotic resistance can spread so fast: one bacterial strain evolves a resistance gene, then shares it like a hacked cheat code with others.

What’s surprising is that even complex organisms, including plants and animals, sometimes carry genes that seem to have arrived by horizontal transfer from bacteria or other organisms. Instead of a strict vertical inheritance from parent to child, evolution occasionally borrows traits from distant cousins. It’s as if the tree of life isn’t just branching; it also has bridges, shortcuts, and hidden tunnels connecting parts you wouldn’t expect to be linked.

Dead Ends, Mass Extinctions, and Second Chances

When we look back at fossils, it’s tempting to think the species that survived were somehow destined to make it. But the fossil record is full of dominant lineages that vanished completely, leaving no direct descendants. Dinosaurs ruled the planet for tens of millions of years, and then a space rock and a chain of environmental shocks cleared the stage, opening niches for mammals to diversify in ways they never could before.

Mass extinctions are like brutal plot twists that rip out entire chapters of the story and force life to improvise new ones. Many of the groups we see as “successful” today only had their big break after older lineages disappeared. This stop-and-start pattern shows that evolution isn’t a smooth climb upward; it’s a messy saga full of accidents, catastrophes, and strange survivors that happened to be in the right place at the right time.

Humans on the Tree: Not the Goal, Just One More Branch

It’s hard not to see ourselves as the main character in the story of life, but evolution doesn’t hand out starring roles. Humans are astonishing in many ways: we reshape landscapes, split atoms, and send probes beyond our solar system. Still, from an evolutionary perspective, we’re just one more twig on a vast and ancient tree that worked perfectly fine without us for billions of years.

Other species are incredibly specialized in ways we can’t match: birds that navigate across oceans using Earth’s magnetic field, insects that communicate using intricate chemical signals, fungi that quietly connect forests into giant underground networks. If humanity disappeared tomorrow, the tree of life would bend and adapt, but it would not stop growing. Recognizing that we’re part of the tree, not perched above it, isn’t just humbling; it makes the whole story of evolution richer, stranger, and more beautiful than any straight line could ever be.