Imagine waking up in a country you’ve never seen, with no phone, no map, no one to ask for help – and somehow still finding your way home, thousands of miles away. That’s everyday life for migrating animals. From tiny butterflies crossing entire nations to birds flying ocean-to-ocean in a single push, their journeys would humble even the most seasoned human traveler.

What makes it even more mind-bending is that many of these animals have never made the trip before. Young birds migrate without “practice runs,” juvenile turtles cross open oceans alone, and insects the size of a paperclip somehow take the right routes season after season. Their secret? A set of internal tools so strange and sophisticated that scientists are still racing to understand them.

The Magnetic Compass Hidden Inside Animal Brains

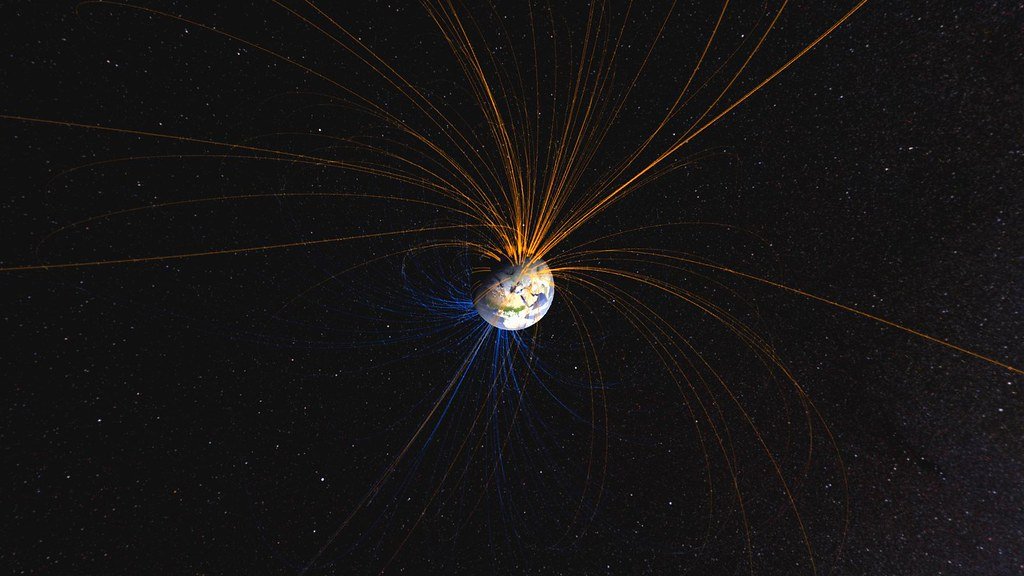

One of the most astonishing discoveries in animal navigation is that many species can literally sense Earth’s magnetic field. It’s like they carry a built‑in compass in their bodies, quietly pointing north and south as they move. Birds, sea turtles, salmon, and even some insects appear to use this magnetic sense to decide which direction to go during migration.

Researchers have found tiny magnetic particles in the tissues of some species, and in others, the eyes themselves seem to detect magnetic fields through light-sensitive chemical reactions. This sense is so subtle that we can’t feel anything comparable, which makes it hard for us to imagine. Yet a young sea turtle, no bigger than your hand, can swim into the Atlantic and navigate along invisible magnetic “road signs” it has never seen before.

Reading the Sun, Stars, and Sky Like a Giant Map

Long before humans learned to navigate by the stars, animals were already doing it with ridiculous precision. Many birds use the position of the sun during the day and constellations at night as guides, adjusting for the time of day like a living clock. They don’t just fly toward the sun; they compensate for its movement across the sky so they can stay on a true course.

At night, some migrating birds orient themselves by the rotation of the night sky around the northern point, like watching the slow turning of a giant celestial wheel. Experiments with birds in planetariums have shown that when the star patterns are shuffled, the birds get confused or change direction. Imagine being able to walk through a city with no street signs and just “feel” where to go by looking up at the sky – for many animals, that’s normal life.

Following Smell Trails Across Oceans and Continents

For animals like salmon, smell is not just a sense; it’s basically a living GPS address. Salmon hatch in freshwater rivers, head out to the open ocean for years, then somehow return to the exact same stream to spawn. Scientists have found that they memorize the unique chemical “smell” of their home waters and later follow that scent gradient back, even after wandering for thousands of miles.

Seabirds such as albatrosses and some petrels also seem to use smell to locate feeding grounds in the vast, featureless ocean. Certain smells, like compounds released by productive patches of plankton, act like invisible signposts saying “food this way.” To us, the open ocean looks like a blank blue desert, but to these birds, it’s more like a scented map full of subtle cues.

Landmarks, Coastlines, and the Power of Familiar Routes

Not all navigation needs to be mysterious. Many animals, especially those traveling over land or along coasts, rely heavily on familiar landmarks. Storks and cranes, for example, often follow river valleys, mountain ridges, and shorelines that act like natural highways in the sky. Once they’ve learned a route, they tend to stick to it year after year.

Over time, these paths become traditional travel corridors used by generations of the same species. Caribou follow ancient migration routes across the tundra, elephants trace well-worn paths between water sources, and even monarch butterflies tend to funnel through particular mountain passes. Think of it as the animal version of a well-known back road your family has been using for decades.

Social Learning: Following Leaders Who Know the Way

Some animals don’t need to be natural-born navigators right from the start because they have older, wiser guides. In species like geese, cranes, or whales, young individuals often migrate alongside experienced adults who already know the route. This is a bit like a child learning to commute by simply taking the same bus as a parent every day.

Over time, these learned routes get woven into the culture of a population. If key leaders are lost, entire groups can struggle to complete their journeys or may shift to different paths. This social learning explains why some migration routes persist for centuries, even as environments slowly change, and why human disruptions can sometimes break that chain of knowledge.

Multi-Sensor “Backup Systems” When One Cue Fails

What’s truly impressive is that animals don’t rely on just one navigation trick. A single bird might combine the magnetic field, the sun’s position, the pattern of polarized light in the sky, wind direction, smells, and terrain to figure out where to go. It’s like running several navigation apps at once and comparing results to stay on track. If clouds hide the stars, the bird can switch to magnetic cues or landmarks below.

This layered system gives them resilience when conditions change. A sea turtle may follow the magnetic field across open ocean but then switch to wave direction and coastline shape near land. In my view, this redundancy is one reason animal migrations can be so robust yet also so fragile: when humans interfere with too many of these signals at once, the whole ensemble can start to fail.

When Human Technology Confuses Animal Navigation

As magical as these natural abilities are, they’re not invincible. Artificial light from cities can lure birds off course, causing them to circle skyscrapers or crash into lit-up buildings during night migrations. Coastal lights can distract baby sea turtles, pulling them away from the ocean instead of toward the moonlit horizon they would normally follow.

There is also growing concern that some types of human-made electromagnetic noise might interfere with animals’ magnetic sensing, at least in certain conditions. Add in habitat loss, wind turbines in key flyways, and polluted rivers that no longer “smell” the same, and you get a serious challenge for species that depend on precise navigation. The more we learn about their internal guidance systems, the more obvious it becomes how easily we can throw them off balance.

Why Animal Navigation Still Stuns Scientists

Even with all the research done so far, big mysteries remain. We still don’t fully understand how a small bird’s brain processes magnetic information into a mental map, or how a monarch butterfly that has never migrated before can head south to a specific patch of mountain forest it has never seen. The pieces we do know sometimes feel like puzzle fragments from different boxes.

For me, that’s part of what makes this topic so gripping: it exposes how limited our own senses are. We build satellites and GPS networks because we can’t do what a juvenile turtle or a sandpiper does naturally. Animals are not just “following instincts” in a vague way; they are running complex, layered navigation systems their bodies evolved over millions of years. The more we uncover, the more it feels like we are only just beginning to read a map they have been using all along.