Imagine waking up tomorrow to the news that scientists have cracked time travel – but there’s a catch. You can only go backward, never forward, and never back to the moment you left. No do-overs, no test runs, no safe return trip. Just a one-way ticket into history.

That single limitation changes everything. It turns time travel from a fun sci‑fi fantasy into a terrifyingly real decision: what would you leave behind, what would you risk breaking, and what hidden chains of cause and effect would you set in motion? Let’s walk through what a past‑only time machine would really mean for our lives, our relationships, and the world.

The One-Way Ticket Problem: Why “Past Only” Changes Everything

The moment you say time travel only works to the past, you turn it into something closer to emigration than tourism. You’re not popping back for a weekend in the 1980s; you’re permanently relocating to a different point on the timeline with no way home. That makes every choice brutally high stakes: you’d be leaving your friends, your family, and your entire future tech-filled life behind, with no guarantee that the past will be kinder than the present.

On top of that, the world you step into won’t be waiting for you like a movie set. It will smell different, feel different, and be far more dangerous in ways we forget: no antibiotics for most of history, no rights for many people, no safety net. A one-way time machine turns into the scariest job offer you’ve ever had: great potential, zero job security, and no exit plan. You’d really have to ask yourself whether any goal – fixing a mistake, saving someone, chasing curiosity – is worth that price.

Would You Kill The Butterfly? The Fragility Of History

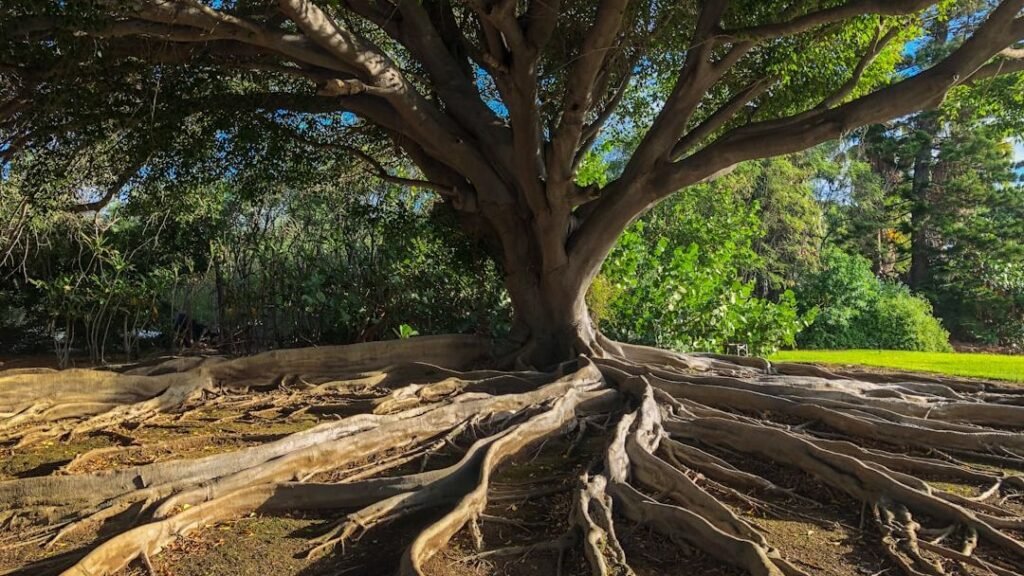

Every story about time travel to the past eventually runs straight into the butterfly effect: tiny actions leading to gigantic consequences. In real life, that’s not just poetic – it’s brutally plausible. If you buy bread from a different baker, take a room someone else would’ve rented, or save a stranger from a minor accident, you might be nudging thousands of lives in directions you’ll never see. History isn’t a sturdy monument; it’s more like a house of cards that somehow hasn’t collapsed yet.

Now imagine arriving with modern knowledge – languages, science, technology, even just awareness of future events. The temptation to “improve” things would be huge, but improvement for whom, and at what cost? You might stop one war only to cause a worse famine, or save one life that would otherwise have inspired social change through tragedy. There’s something humbling and a little horrifying in realizing that even your most well-meaning action could ripple out into a future that feels nothing like the one you left.

Could You Actually Change The Future, Or Is It Already Written?

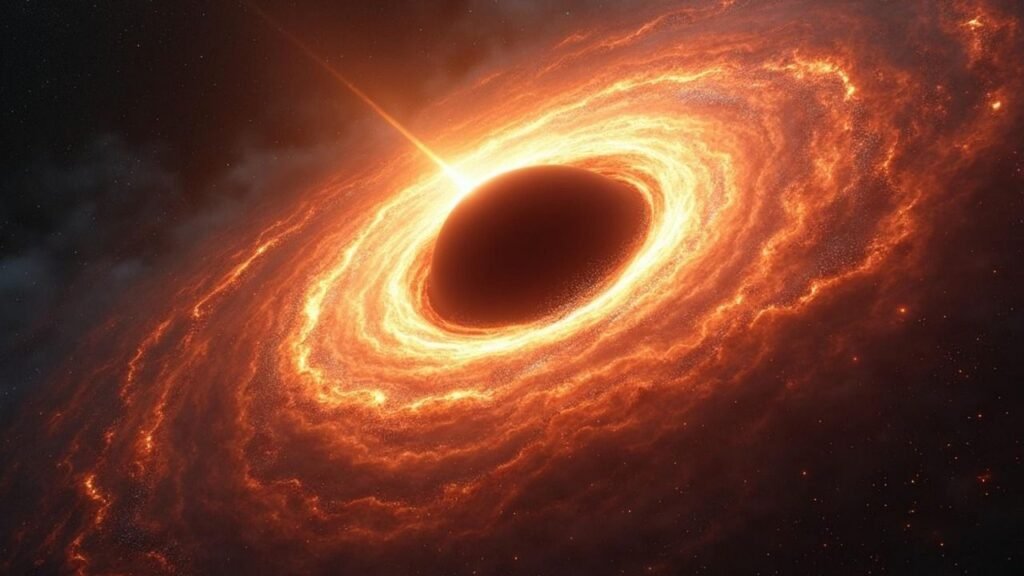

One of the big philosophical showdowns here is between two ideas: the universe is flexible and can be changed, or it’s fixed and you were always meant to go back. In the first case, you’re genuinely rewriting the future, meaning that every step you take might erase your own timeline – including the very discovery of time travel. In the second, you’re not changing history at all; you’re just filling in a blank that was always there, like finally discovering a piece of a puzzle that’s been on the table all along.

Some physicists and philosophers lean toward the idea that if time travel to the past is possible, reality might “protect” itself from paradoxes. You’d try to stop your grandparents from meeting, and circumstances would endlessly conspire to stop you. That sounds comforting until you realize what it implies: you might have free will within narrow lanes, but the major events are locked in. In that world, going back might feel less like a heroic mission and more like stepping into a script you can’t fully rewrite, no matter how hard you push.

Meeting Your Younger Self: Healing Or Psychological Disaster?

If traveling to the past were real, a lot of people wouldn’t aim for world wars or famous moments – they’d aim for their own childhoods. The urge to go back and fix something deeply personal is powerful: a cruel comment, a breakup, a lost opportunity, a person you failed. But actually standing in front of your younger self, older and full of knowledge they can’t yet understand, might be more emotionally explosive than any sci‑fi story makes it look. You’re not just revisiting memories; you’re confronting the raw version of you, before all the defenses and rationalizations formed.

Would you try to warn them? To prevent their pain? If you succeed, you might erase the very lessons that made you who you are. If you fail, you’re forced to watch them walk straight into the same heartbreak, knowing you can’t pull them off the track. And then there’s the darker angle: what if your younger self simply doesn’t like you? What if they find you disappointing, bitter, or too cautious? For a lot of people, that could cut deeper than any world-level consequence.

The Ethics Of Fixing History: Who Gets To Decide What Was “Wrong”?

Once we open the door to the past, we also open the ugliest moral question: who has the right to change it? You might want to prevent genocides, pandemics, or catastrophic wars. At first glance, that feels obviously good. But even there, you’re deciding for billions of people what their history should be, including those who found meaning, art, love, and identity in the shadow of those events. Erasing a horror might also erase the solidarity, reforms, and hard-won wisdom that came from surviving it.

There’s also power to consider. If governments or corporations controlled time travel, they’d be sorely tempted to “correct” unfavorable outcomes: elections, revolutions, market crashes, social movements. The people with access could sculpt reality to lock in their advantage, making the world look stable on the surface while turning it into a rigged game underneath. Suddenly, the question isn’t just “what would you fix?” but “should anyone be allowed to fix anything at all, knowing the cost of getting it wrong?”

Living As A Time Refugee: Surviving In A World That Doesn’t Know You

A one-way jump into the past doesn’t just change history; it strands you as a stranger in a world that never expected you. You’d need documents, money, a believable backstory, and skills that make sense in that era. Your modern habits would betray you in small ways: how you hold a phone that doesn’t exist yet, how casually you talk about rights that haven’t been fought for, how your body language clashes with the norms of the time. You wouldn’t belong, and people would feel that even if they couldn’t say why.

On top of that, the loneliness would be brutal. Everyone you know is either not born yet or radically different. You’d carry the knowledge of future music, movies, tragedies, and breakthroughs that no one around you can share. It’s like being the only person in a room who’s seen the ending of the story, but you’re not allowed to tell anyone without sounding insane. Over time, you might adapt, fall in love, build a life – but somewhere in the back of your mind, you’d always be split between two epochs, a permanent guest in someone else’s present.

Would Time Travel Ruin The Present We Have Now?

If people started jumping into the past, even rarely, the present might slowly become unrecognizable. Entire industries would form around preparing “chrononauts”: training them in languages, history, survival skills, and quiet influence. At the same time, the rest of us might start doubting the stability of our own timeline. When something strange happens – a sudden breakthrough, an unlikely event – you’d always wonder whether some time traveler nudged the dominoes a decade earlier.

There’s also a quieter danger: addiction to the idea of “fixing” things instead of facing them. Whenever society hits a major problem – climate change, inequality, political tension – people might start fantasizing not about changing policy now, but about finding a way to go back and stop it in its early stages. That mindset can be paralyzing. It encourages regret over responsibility, nostalgia over action. If we’re not careful, the dream of a time machine to the past could become a convenient excuse to avoid doing the hard, unglamorous work of improving the present we actually live in.

The Past Is Tempting, But The Cost Is Real

If time travel to the past were real, it wouldn’t just be a cool gadget; it would be the most dangerous, emotionally loaded tool humanity has ever touched. It would tempt us with second chances and cleaner histories, while quietly threatening our sense of identity, ethics, and responsibility. Every trip would be a gamble not just with your life, but with the lives and futures of countless people who never agreed to play.

Maybe the most sobering thought is that we already time travel, just at one speed: forward, together, with no do-overs. The choices we make now will be someone else’s unchangeable past, their fixed point in history they can only study, not escape. Knowing that, the question becomes less “What would you change if you could go back?” and more “What are you doing today that you wouldn’t dare someone from the future to undo?”