Somewhere on our planet, older than the pyramids, older than written language, an organism is quietly alive, growing so slowly it almost feels like time forgot it. It doesn’t roar like a lion, tower like a skyscraper, or glow like a galaxy, yet it has outlived empires, religions, and entire species. The world’s oldest living beings are not always the biggest or the most obvious; they’re often hidden in plain sight, disguised as ordinary trees, unremarkable shrubs, or fragile-looking mats of grass.

What makes this topic both thrilling and strangely humbling is that even in 2026, scientists are still arguing over what exactly deserves the title of “world’s oldest living organism.” Is it a single tree you can walk up to and touch? A vast underground network of roots and clones stretching across a hillside? Or a colony of microscopic creatures frozen beneath the earth, quietly pulsing with life? The answer is not as simple as a single name and a number of years – and that’s where the story gets really interesting.

An Organism Older Than Empires: Meet the Ancient Clonal Giants

The real contenders for the world’s oldest living organism are often clonal colonies – huge living systems made of many genetically identical stems or shoots, all connected to the same root network. One of the most famous examples is a quaking aspen colony nicknamed Pando in the western United States, estimated to span dozens of hectares and weigh as much as a blue whale multiplied many times over. Each individual tree trunk you see is like a finger of the same body, sprouting and dying over centuries while the core genetic individual persists. Scientists studying such colonies estimate that some of them may be tens of thousands of years old, predating human agriculture.

What makes these clonal giants so mind-bending is their strange relationship with time. If you looked at a single trunk, you might think it’s just another middle‑aged tree, nothing special at all. But underground, there’s this enormous, ancient being that has survived fires, storms, droughts, and changing climates over periods of time so long they’re hard to even picture. Thinking about it feels a bit like realizing that a city is not just its buildings, but its whole history and infrastructure beneath your feet. The organism that wins the “oldest” prize may not be a single trunk, but the massive, hidden network tying it all together.

Single Trees That Have Watched Civilizations Rise and Fall

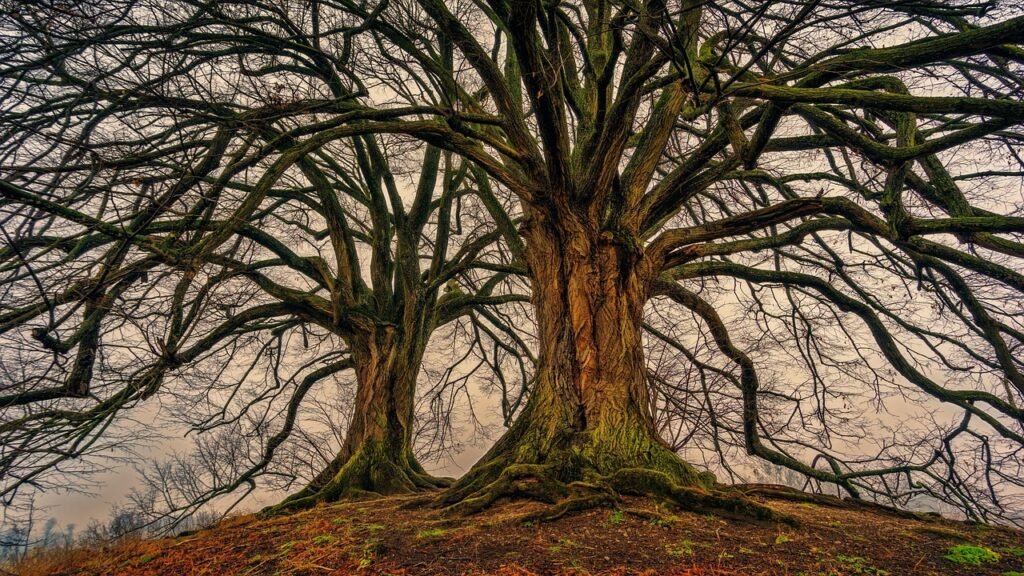

Even if clonal colonies are technically older, there’s something deeply emotional about a single tree that has stood more or less in the same place for thousands of years. In cold northern landscapes, bristlecone pines hold records for some of the oldest non-clonal individual trees ever measured. Some of these gnarled, twisted pines are estimated to be nearly five thousand years old, meaning the same living organism has been there since before many ancient civilizations were founded. Their wood is so dense and slow-growing that fallen trunks can remain on the landscape for thousands more years, like a time capsule of climate and history.

Seeing photos of these trees, they don’t look majestic in the classic postcard sense; they look worn, almost skeletal, as if the wind and ice carved stories into their bark. That’s part of what makes them oddly moving. You’re not just looking at a plant; you’re looking at a being that has survived brutal winters, volcanic dust, shifting temperatures, and human activity long before humans even knew it existed. It’s like meeting a living observer of history that never wrote anything down but still remembers everything through its rings.

Oldest Does Not Always Mean Biggest: Tiny Survivors of Deep Time

When people imagine something that has lived for tens of thousands of years, their minds jump to giant trees or sprawling forests, but some of the planet’s most ancient life forms are almost comically small. In polar deserts and extreme mountain regions, there are lichens that have been growing on the same rocks for potentially several thousand years. They spread so slowly that scientists can measure their growth in fractions of millimeters over decades. Bacteria and microbial communities trapped beneath ice sheets, in deep-sea sediments, or inside salt crystals can remain in a low‑activity state for unimaginable stretches of time and still technically count as alive.

These tiny elders of the biosphere don’t look impressive at all if you just glance at them. You might even step on some of them without realizing you’ve just crushed something older than your entire family line. Yet the fact that such small, fragile-looking organisms can endure in conditions where most life would instantly die is almost more impressive than towering trees. It’s like discovering that the quiet, unassuming person in the room has the most incredible, centuries-long story, but never felt the need to brag about it.

How on Earth Do Scientists Measure Such Extreme Age?

Claiming that a living organism is thousands or tens of thousands of years old is a big statement, and scientists have to be careful about how they make it. For single trees, researchers can often use tree rings, a method called dendrochronology, to count years of growth. Where cores cannot be taken safely, age estimates can also be based on growth rates and comparisons with similar, already‑measured trees. For extremely old dead wood or ancient clones, scientists may use radiocarbon dating on roots or other buried material to estimate how long the genetic line has persisted. Each method comes with uncertainty, which is why debates over “the oldest” organism never fully disappear.

Clonal organisms pose an extra challenge because the visible parts – like grass blades, stems, or trunks – might only be a few decades or centuries old, while the underlying genetic individual could have persisted for millennia. To get around this, researchers look at mutation rates in DNA, the spread of the clone over the landscape, and long-term environmental records. It’s a bit like forensic detective work, piecing together small clues to reconstruct an almost unimaginable timeline. This is also why scientists tend to speak in ranges and estimates rather than a neat, exact birthday for these organisms.

Why Age Alone Does Not Make Something “The Oldest”

One of the most surprising things about trying to crown the world’s oldest living organism is how philosophical it becomes. Do we count an organism that has been genetically continuous, even if it constantly replaces its physical parts, like a clonal colony? Or do we reserve the prize for a single continuous body, such as a solitary tree, that has never divided or spread into many individuals? It’s a bit like asking whether a city that keeps rebuilding itself is the same city as it was a thousand years ago. The answer depends on how you define identity over long stretches of time.

Some researchers argue that clonal colonies, while astonishingly old, feel more like ancient lineages than ancient individuals, since they’re constantly regenerating and replacing themselves. Others point out that most animals and humans also constantly renew their cells, yet we still consider ourselves the same person. This tension means there might never be universal agreement on a single “winner,” and honestly, that uncertainty makes the story more intriguing. Instead of one champion, we get a whole cast of different champions, each representing a different way life can cling to existence for jaw‑dropping periods of time.

Why These Ancient Organisms Matter in a Warming, Changing World

It might be tempting to treat stories about ancient trees and microscopic survivors as fun trivia, the kind of thing you pull out at a party to sound interesting. But these organisms are far more than curiosities; they are living archives of climate and environmental history. Tree rings can record droughts and volcanic eruptions, ice‑trapped microbes reveal conditions from ages long before humans were keeping records, and long‑lived colonies show how ecosystems respond to gradual change. In a century defined by rapid climate shifts, this kind of natural memory is priceless. It helps scientists understand how life has survived past upheavals and what might happen as our current crisis deepens.

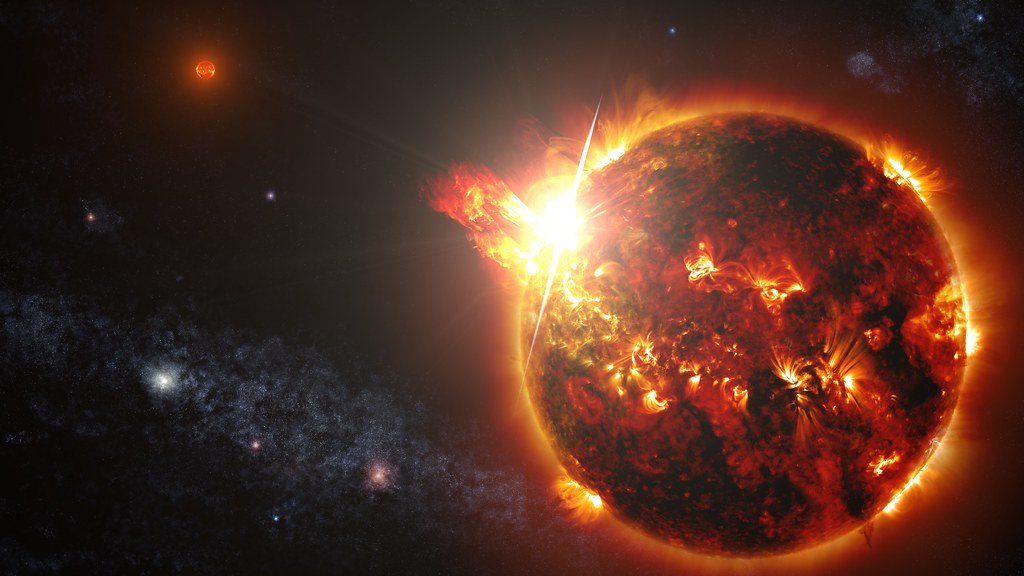

There’s also an emotional and ethical layer here that’s hard to ignore. Some of the oldest organisms on Earth are already under threat from logging, development, tourism, and a heating climate that is pushing them beyond the conditions they evolved to endure. The idea that a being which has survived multiple ice ages could finally die because we wanted a new road, ski resort, or Instagram photo is hard to swallow once you’ve really thought about it. Protecting these ancient life forms is not just about science; it’s about deciding what kind of relationship we want to have with a planet that has been quietly nurturing them for longer than our own species has existed.

What the World’s Oldest Organisms Teach Us About Time and Ourselves

Spending time learning about the world’s oldest living organisms has a strange way of shrinking your daily worries. Deadlines, notifications, the latest argument online – none of it would even register on the timescale of an organism that measures its life not in years, but in millennia. When you imagine a tree that started growing before your ancestors had a written language, or a clonal colony that may have witnessed entire ecosystems come and go, your own lifetime starts to feel shorter but also more precious. It’s like stepping back from a painting and realizing you’re just one tiny brushstroke in a massive, ongoing work of art.

There’s also something grounding in the idea that resilience doesn’t always look dramatic. The oldest living things on Earth are not racing, conquering, or constantly changing; they’re just persistently, stubbornly there. They adapt slowly, hold on quietly, and let time do what it does while they continue existing. In a world obsessed with speed and novelty, that kind of long, patient survival might be the most radical thing of all. It leaves a quiet question hanging in the air: in the end, what really matters more – burning bright and fast, or enduring, almost unnoticed, long enough to see ages come and go?