For decades, warp drives lived in the same mental box as dragons and lightsabers: fun to imagine, totally impossible. Then, quiet papers started appearing in physics journals, and small, serious teams began talking about bending spacetime not as fantasy, but as engineering. The tone shifted from never to maybe, and now, in 2026, to something even more startling: we might actually know how to start building a physical warp drive on the lab bench.

This doesn’t mean starships are launching next summer. It does mean that respected physicists are no longer rolling their eyes when the term “warp drive” shows up in a conference title. The conversation has moved from “this violates physics” to “this is insanely hard, but the math checks out, and here’s a prototype-scale design.” That shift is huge, and honestly, it’s a little disorienting, like waking up to find out your favorite sci‑fi prop has quietly turned into a line item in a grant proposal.

The Sci‑Fi Idea That Refused To Die

Let’s start with the elephant in the room: warp drives come with a lot of baggage. For most people, the phrase instantly conjures up images of starships streaking through space, captains shouting impossible orders, and engines roaring with cinematic drama. For a long time, serious scientists wanted nothing to do with that image, because it sounded like a shortcut that ignored the speed of light, one of the most sacred limits in physics.

The twist is that general relativity never said you can’t bend space itself, it just said you can’t move through space faster than light. That subtle difference is where the warp idea dug in its claws and refused to go away. Instead of throwing the concept in the trash, a few stubborn researchers kept asking: what if the ship doesn’t move faster than light, but spacetime does the moving for it? It sounded like a loophole, but in physics, loopholes are often where the most interesting discoveries live.

From Alcubierre’s Thought Experiment To Real Equations

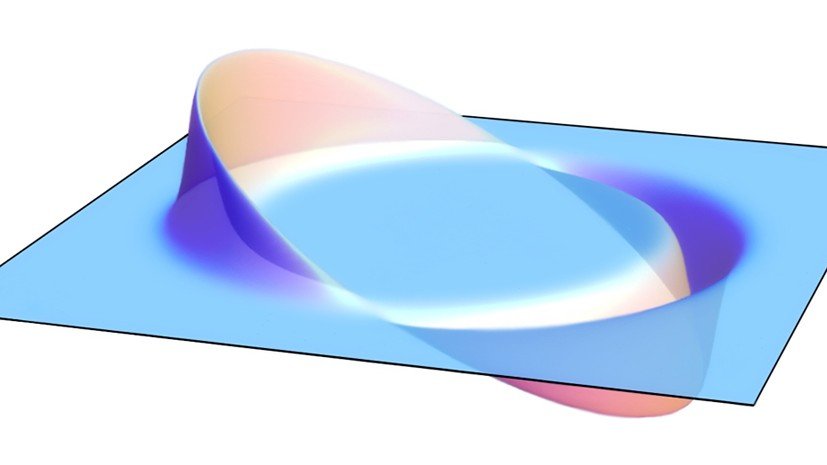

The modern warp drive story kicked off in the mid‑1990s with physicist Miguel Alcubierre. He wrote down a solution to Einstein’s equations that looked almost like a love letter to science fiction: a “warp bubble” of flat spacetime carrying a ship, with space contracting in front and expanding behind. Inside the bubble, the ship would just float, but from the outside, the bubble itself could move faster than light without technically breaking relativity.

There was one devastating catch: Alcubierre’s design required absurd amounts of “exotic” matter with negative energy density, a material no one knew how to create in bulk. The required energy was initially calculated to be more than the mass‑energy of the visible universe, which is about as close to a cosmic “nope” as physics gets. Still, the math was solid, and that made people uneasy in the best possible way. The idea lingered, waiting for someone to come along and ask if the numbers could be tamed.

Recent Breakthroughs: Shrinking The Impossible

In the last few years, several research groups have attacked the warp problem from a new angle: treat it like an engineering optimization challenge, not a wild fantasy. Instead of assuming a big ship and a dramatic bubble, they asked how small and energy‑efficient a warp configuration could be, if you squeeze every parameter you can. Bit by bit, the required energy budget has dropped from universe‑sized, to star‑sized, to something closer to hypothetical high‑energy technology levels.

One especially intriguing direction involves rethinking the geometry of the warp bubble. By changing its shape, thickness, and how mass or fields are distributed, researchers have found configurations that need far less exotic energy, and in some cases rely more heavily on positive energy densities we understand better. Conceptual designs have shifted from “impossibly huge, forever out of reach” to “still outrageous, but now in the realm of long‑term technological ambition.” That’s a subtle but profound change; it moves warp drives from fantasy to the far edge of feasibility.

Why Physicists Say A Physical Warp Drive Is “Now Possible”

When , they don’t mean we can bolt one onto a spaceship today. They mean that, for the first time, the equations describe a device that could in principle be built out of known or reasonably extrapolated physics, instead of demanding infinite energy or materials that violate basic laws. The latest models propose compact configurations, on scales closer to laboratory apparatus than to interstellar cruisers, where spacetime could be measurably distorted in a controlled way.

This is a huge psychological shift inside the field. Once something moves into the “in principle possible” category, it changes how people allocate time, money, and brainpower. It becomes a candidate for small, incremental experiments instead of a topic reserved for after‑dinner speculation. The phrase “physical warp drive” now points to concrete designs with parameters you can plug into software, not just loose sketches on a whiteboard, and that’s exactly how real technologies tend to begin.

What A Lab‑Scale Warp Experiment Might Actually Look Like

Forget gleaming spaceships for a moment; a first warp device would probably look disappointingly boring. Picture a cluster of high‑voltage equipment, vacuum chambers, coils, and sensors stuffed into a room, more like an MRI machine’s anxious cousin than a starship engine. Instead of zipping off to Alpha Centauri, the goal would be to produce tiny distortions in spacetime – so small they might need extremely sensitive interferometers or atomic clocks just to detect them.

Such an experiment might use intense electromagnetic fields, engineered materials, or cleverly arranged masses to approximate the energy distribution of a theoretical warp bubble. The win would not be speed, but proof: a clear, repeatable measurement that spacetime itself responded in the predicted way. Once you have that, even at a microscopic scale, you’ve crossed a line. You’re no longer just solving equations; you’re poking the fabric of the universe and watching it wiggle back.

The Brutal Challenges: Energy, Materials, And Safety

Even with optimistic models, the energy requirements for any meaningful warp effect are still brutal by current standards. We’re talking about levels far beyond what a typical city consumes, concentrated into highly controlled configurations that must be stable, tunable, and safe. Managing that kind of power without melting, exploding, or simply shorting out your experimental setup is a non‑trivial engineering nightmare, and that’s before you worry about side effects.

On top of energy, there’s the question of materials and field control. We’d likely need ultra‑advanced superconductors, high‑energy lasers, or exotic states of matter that push manufacturing to its limits. And then there’s the ethics: if you can bend spacetime, what happens if you do it in the wrong way, or in the wrong place? No one wants to accidentally build a very small, very unfriendly gravitational trap in a lab. Warp drive research sits at this strange intersection of hope and caution, where responsible progress means admitting you don’t yet know all the ways it could go wrong.

Why This Matters Even If We Never Leave The Solar System

It’s easy to dismiss warp drive research as a distraction from “real” problems, but history says otherwise. Whenever humanity pushes on the wild edges of physics, we tend to stumble onto side benefits no one saw coming. Chasing nuclear fusion gave us better materials science and plasma physics. Digging into quantum mechanics gave us lasers, transistors, and GPS. Even if a practical interstellar drive remains centuries away, the tools developed along the way could reshape energy, computation, and transportation here at home.

There’s also a less tangible payoff: ambition. A civilization that seriously works on bending spacetime is a civilization that expects to be around for a long time, and that mindset can spill over into how we treat our planet and each other. Warp drive research forces us to think on longer timescales, to accept that some projects may take generations, and to see ourselves as part of a much bigger cosmic story. That sense of perspective can be quietly radical in a world obsessed with quick wins and short attention spans.

The Road Ahead: From Equations To Engines

Right now, the warp drive story lives in an awkward but exciting middle phase: the math is promising, the lab proposals are forming, but the hardware is mostly still on paper. The next decade or two will likely be defined by small, incremental experiments that test pieces of the theory, rather than dramatic leaps. That might feel underwhelming if you were hoping for starships, but anyone who’s watched other radical technologies mature knows this is just how it goes. First you learn to make something twitch, then you learn to make it move on command.

If the research continues, we’ll probably reach a point where we can reliably generate and measure tiny spacetime distortions in controlled settings. From there, the challenge becomes scaling, just as it did for early flight, electricity, and computing. Will that scaling be miserably hard, or merely extremely hard? No one knows yet, and that uncertainty is part of what makes this moment so compelling. The idea that humans might one day surf a self‑created wave in spacetime is no longer pure fantasy; it’s a question of time, ingenuity, and how far we’re willing to push.