Imagine standing under a storm where the raindrops are not water, but glittering diamonds or sharp shards of glass. It sounds like something out of a sci‑fi movie, but for some worlds in our solar system, this kind of weather may be completely normal. The deeper astronomers look into the atmospheres of giant planets and exotic worlds, the stranger and more dramatic the story of alien weather becomes.

We like to think of space as cold, silent, and empty, but it’s also home to violent winds, crushing pressures, and temperatures that can turn ordinary elements into something wild. From diamond showers deep inside giant planets, to molten glass storms whipping sideways at extreme speeds, the universe has its own twisted idea of “rainy days.” Let’s dive into how scientists think these storms actually work, and why they might be more real than they sound.

Diamond Rain on Ice Giants: Why Scientists Think It’s Real

It sounds like pure fantasy: Uranus and Neptune, the quiet blue “ice giants” on the edge of our solar system, might be places where it literally rains diamonds. Yet this idea doesn’t come from science fiction writers, but from physicists and planetary scientists running high‑pressure experiments. Deep inside these planets, pressures are many millions of times higher than what we feel at Earth’s surface, and temperatures soar to thousands of degrees.

In labs on Earth, researchers have squeezed materials that mimic the atmospheres of Uranus and Neptune – rich in methane, carbon, hydrogen – using powerful lasers and shockwaves. Under those intense conditions, the carbon appears to separate and form tiny diamond crystals, just for a brief moment, before the material is released. This suggests that inside the real planets, where those conditions are stable over vast depths, diamond formation might not just be possible, but constant and widespread.

How Diamond Rain Might Actually Form Deep Inside Planets

To understand how diamond rain could work, think of Uranus or Neptune as enormous pressure cookers. Their outer layers are made of gases like hydrogen, helium, and methane, but as you go deeper, everything is crushed and heated beyond anything we can experience on the surface of Earth. Methane, which is a simple carbon‑based molecule, gets pulled apart by heat and pressure, freeing carbon atoms.

Those carbon atoms, under just the right combination of heat and compression, can rearrange into the crystal structure of diamond, the same structure that makes your jewelry so hard and sparkly. Once formed, the dense diamond crystals would be heavier than the layers above them, so they’d start to sink – like hailstones falling in reverse, deeper into the planet instead of down through an open sky. Over time, this could create layers or even “rivers” of diamond inside the planet’s mantle, slowly drifting toward its core.

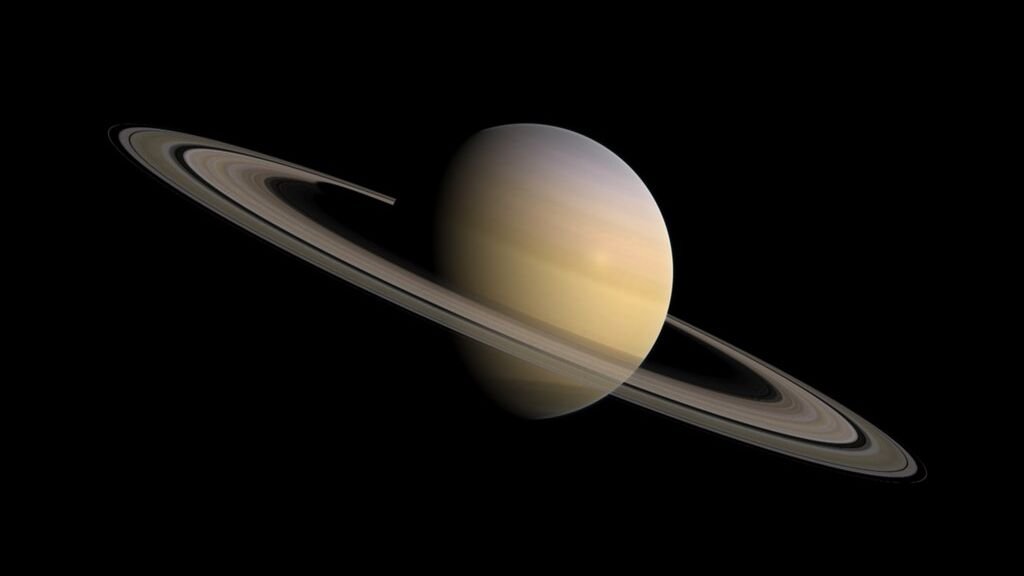

Why Saturn and Jupiter Might Also Have Hidden Diamond Storms

Uranus and Neptune get most of the diamond‑rain headlines, but giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn might have a similar trick going on inside them. Their atmospheres are dominated by hydrogen and helium, but they also contain carbon in different forms, like methane and other hydrocarbons. As lightning flashes through those upper layers and storms churn the gases, complex chemistry can break and rebuild molecules in surprising ways.

Some models suggest that carbon could first appear as soot, like the black smoke from a candle flame. Deeper down, that soot could compress into graphite, the material found in pencil leads, and then, even deeper, be forced into diamond form. So you’d have a kind of carbon weather cycle: soot clouds turning into graphite rain, which then gradually transforms into falling diamonds. It’s a wild thought that beneath Jupiter’s colorful cloud bands, huge hidden storms could be quietly manufacturing jewels.

Rains of Glass on Distant Worlds: The Case of HD 189733b

If diamond rain feels extreme, the weather on some known exoplanets makes it look almost gentle. One famous example is a world called HD 189733b, a gas giant orbiting a star about sixty light‑years away. It’s often described as a deep blue planet, a color that might come from silicate particles – tiny bits of glass – suspended in its atmosphere. Observations from space telescopes have hinted that this atmosphere is not only full of heat but also extremely turbulent.

On this world, winds likely tear across the planet at speeds of thousands of kilometers per hour, far faster than even the worst hurricanes on Earth. In that chaos, tiny glass‑like particles can condense and be flung sideways through the atmosphere, turning storms into sandblaster‑style nightmares. Instead of gentle raindrops pattering on the ground, you’d have microscopic blades of glass scouring everything in their path. It’s the kind of place that makes Earth’s worst storm seem like a light drizzle.

Sideways Rain and Supersonic Winds: Weather That Defies Intuition

On Earth, we’re used to rain falling mostly straight down, maybe slanting a bit in strong wind. On many alien worlds, “down” is almost a minor detail compared to the horizontal violence of their winds. Some hot Jupiters – giant planets that orbit incredibly close to their stars – are locked with one side always facing the star, like the Moon is locked to Earth. That creates an enormous temperature difference between the scorching day side and the cooler night side.

Nature hates imbalance, so the atmosphere rushes to even out those extremes, generating winds that can rip around the planet faster than sound. Any solid or liquid particles forming in those conditions – metal droplets, silicate dust, glass grains – get blasted sideways rather than gently falling. Imagine trying to walk through a sideways waterfall made of hot glass shards traveling at supersonic speed. It’s almost funny to call it “rain” when it behaves more like a planet‑sized sandstorm from a nightmare.

How Scientists Study Alien Rains Without Ever Visiting

We obviously haven’t sent probes into diamond storms or glass hurricanes yet, so how do we know any of this is even close to true? The answer is a mix of clever observation and brute‑force physics. Telescopes that can detect different wavelengths of light, from infrared to ultraviolet, let scientists see how a planet’s atmosphere absorbs and emits light. From those patterns, they can guess what kinds of molecules are up there and at what temperatures.

Meanwhile, in high‑energy physics labs, teams recreate tiny pieces of those extreme environments using lasers, shockwaves, and powerful presses. They take materials like methane or water, crank up the heat and pressure, and watch what happens using ultra‑fast instruments. When the lab behavior matches what the telescopes suggest, the story starts to hang together. It’s a bit like piecing together a crime scene you’ll never visit, using only distant security footage and small‑scale reenactments.

What Alien Storms Reveal About Planets, Including Our Own

As bizarre as diamond rain and glass storms sound, they’re not just fun trivia. They tell us something deep about how planets work and how common different types of worlds might be across the galaxy. If diamond formation is normal inside giant planets, it affects how heat flows, how magnetic fields are generated, and how those worlds evolve over billions of years. That in turn helps explain why some planets have calm, thin atmospheres while others are raging, windy monsters.

There’s also a more personal angle: seeing how wild other worlds can be changes how we feel about Earth. Our storms can be deadly, but they exist in a narrow, life‑friendly window – water instead of molten rock, gentle gravity instead of crushing pressure. I remember the first time I really thought about glass rain blasting sideways at unimaginable speeds; suddenly, a gray rainy day here felt almost comforting. In a universe where storms can build diamonds and hurl glass, a simple water shower under a cloudy sky feels like a quiet miracle.