Every now and then, archaeologists pull something out of the ground that just should not exist. A figurine in the wrong era, a tool too advanced for its time, or an entire city buried where no city was supposed to be. These finds don’t just puzzle experts; they quietly whisper that the story of us, humans, might be far messier, older, and stranger than the simple timelines we learned in school.

None of the artifacts in this list “prove” lost civilizations or time travelers, and serious researchers are usually much more cautious than internet legends suggest. But even when the myths are stripped away, a hard core of real mystery often remains. That’s where things get really interesting: in the gap between what we can measure and what we can honestly explain. Let’s step into that gap and look at a dozen artifacts that keep poking holes in what we think we know about human history.

The Antikythera Mechanism: An Ancient Greek “Computer”

The Antikythera mechanism was pulled from a shipwreck off a Greek island in the early twentieth century, and for decades it looked like nothing more than a lump of corroded bronze. Only later did researchers realize it was an intricate device packed with interlocking gears, dials, and inscriptions, built around the second or first century BCE. That alone makes it shocking: it’s essentially an ancient mechanical computer that could predict eclipses and track the movements of the sun, moon, and probably planets.

Modern CT scanning and 3D reconstructions have shown dozens of carefully cut bronze gears inside, some with teeth so fine they rivaled precision metalwork from nearly two thousand years later. The mechanism suggests that ancient Greek engineers had a level of technical complexity that was lost for a very long stretch of history. There’s no evidence of aliens or anything supernatural here – just humans being far more ingenious than our tidy timelines usually allow. It raises a blunt question: if something this advanced survived only as fragments on the seafloor, what else might have been built and completely vanished without a trace?

Göbekli Tepe: A Monument Older Than Cities

On a hill in southeastern Türkiye lies Göbekli Tepe, a complex of massive stone circles and carved pillars that predates Stonehenge by thousands of years. Radiocarbon dating puts some of the earliest phases back to around twelve thousand years ago, long before the conventional beginning of organized agriculture and settled life. Yet here we see monumental stone architecture, sophisticated planning, and astonishing artistic carvings of animals and abstract symbols.

What scrambles the usual story is that Göbekli Tepe seems to have been built by hunter-gatherers, not farmers, at a time when humans supposedly lived in small, mobile bands. The site hints that spiritual or ceremonial centers may have come first, pulling people together and perhaps even nudging them toward agriculture rather than the other way around. That flips a familiar script: instead of “farming created complex society,” places like this suggest that big, shared beliefs and gathering places might have helped create farming. It doesn’t tear history apart, but it does force us to redraw the earliest chapters with a heavier pencil.

The Baghdad “Battery”: Ancient Power Source or Misunderstood Pot?

In the late 1930s, a small ceramic jar with a copper cylinder and an iron rod inside was found near modern Baghdad, in the area of ancient Mesopotamia. When filled with an acidic liquid like vinegar or lemon juice, replicas of this object can produce a faint electric current. This sparked the idea of the “Baghdad Battery,” a supposed ancient power source from around two thousand years ago or more. The image of old priests electroplating jewelry or shocking believers in temple rituals is irresistible.

Professional archaeologists are far more cautious and point out that there’s no direct proof the jar was used as a battery at all; it could have been a simple container or even a scroll holder, and the electrification demo might just be a neat coincidence. Still, the materials and structure are undeniably battery-like, and the fact that such a configuration existed in antiquity is enough to make people wonder. Even if it was never used for electricity, it reminds us how easily function is lost when context disappears. We might be looking at the remains of an everyday tool and completely missing what it really meant to the people who built it.

The Piri Reis Map: Ancient Knowledge of Unexpected Coasts

In 1929, a map drawn by the Ottoman admiral Piri Reis in the early sixteenth century was rediscovered in Istanbul. At first glance, it’s just a beautifully detailed chart of parts of Europe, Africa, and the Americas. What makes it controversial is that the admiral himself claimed to have compiled it from many older sources, some allegedly going back to classical times. Parts of the coastline are surprisingly accurate for such an early period of global exploration.

Enthusiasts have pushed the map’s mystery much further, arguing that it shows Antarctica or ice-free coasts that humans supposedly could not have known. Those extreme claims don’t hold up well under closer inspection, but they grew from a real kernel: early navigators sometimes used older charts that have since vanished. The Piri Reis map suggests we are missing whole layers of cartographic knowledge that once circulated between cultures. It doesn’t prove an impossibly ancient global civilization, but it does hint that the history of exploration and information-sharing is more entangled and patchy than a clean linear timeline suggests.

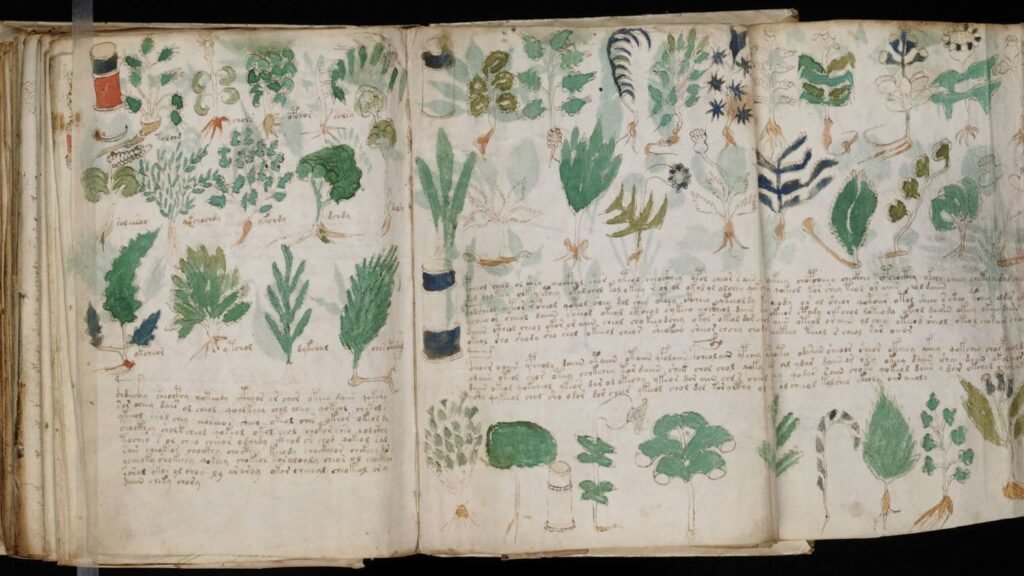

The Voynich Manuscript: A Book No One Can Read

The Voynich Manuscript looks like the ultimate medieval oddity: a richly illustrated book filled with strange plants, zodiac diagrams, nude figures in mysterious pools, and page after page of text in an unknown script. Radiocarbon testing of the parchment places it in the early fifteenth century, so it’s not a modern fake. Yet after decades of effort by linguists, cryptographers, and even code-breaking experts, no one has convincingly deciphered the writing or agreed on a definite language behind it.

Some researchers suspect a clever hoax, created to impress a wealthy patron with a “secret knowledge” that never existed. Others argue that the statistical structure of the text behaves too much like a real language to be simple nonsense. A few new theories pop up every few years – an obscure dialect, a shorthand system, an encoded medical text – but none has gained broad acceptance. Whatever it is, this manuscript shows that even in a well-documented period like medieval Europe, a single surviving book can still rupture our sense that everything important is already understood.

The Saqqara Bird: Toy, Symbol, or Prototype Glider?

In a tomb at Saqqara in Egypt, dating to roughly two thousand years ago, archaeologists found a small wooden object shaped like a bird with surprisingly aerodynamic wings. Its design led some modern observers to suggest it could be an early experiment in gliding, an echo of a lost understanding of aerodynamics. It doesn’t look much like typical Egyptian animal figures, which only adds to its mystique.

Most Egyptologists believe it was probably a simple toy, a symbolic object, or perhaps a ritual model tied to the soul’s flight in the afterlife. There’s no hard evidence of ancient Egyptians building aircraft or anything close to it. Still, the fact that it flies reasonably well when reproduced has made it a favorite for those who like to push at the edges of accepted history. For me, the Saqqara Bird is a good reminder that not every unusual shape hides a radical secret, but every time we jump too quickly to “just a toy,” we might be brushing past a moment of genuine ancient curiosity and experimentation.

Puma Punku: Stonework That Defies Simple Explanations

High on the Bolivian altiplano, near Lake Titicaca, lies the ruined complex of Puma Punku, part of the larger Tiwanaku archaeological site. Scattered across the area are enormous stone blocks, some weighing many tens of tons, cut with sharp edges and intricate, interlocking shapes. The precision of the right angles and the neat drilled holes have led to endless claims about lost technologies or even non-human builders. The stones look like massive stone Lego pieces, designed to slot together in ways that seem surprisingly modern.

Archaeologists date the main phases of Tiwanaku and Puma Punku to well within the last few thousand years, long after humans in the Andes had developed tricky engineering methods and organized labor for monumental construction. From that perspective, the site is still extraordinary but not supernatural. What makes Puma Punku so compelling is the way it exposes our bias: we often underestimate ancient people’s ability to work stone, organize huge workforces, and execute precise plans using simple tools. The real “mystery” might be how quickly we forget what determined humans can do when they’re stubborn and patient enough.

The Indus Valley Seals: Messages From a Silent Script

Across sites in modern Pakistan and northwest India, archaeologists have unearthed thousands of small seals from the Indus Valley Civilization, which flourished more than four thousand years ago. Many show animals and symbols, along with a line or two of script that appears on pottery, weights, and other artifacts. This civilization built planned cities with straight streets, drainage systems, and standardized weights and measures, yet its writing remains undeciphered.

Unlike Egyptian hieroglyphs or Mesopotamian cuneiform, the Indus script has not yielded to modern decoding efforts, partly because we lack long bilingual texts or “Rosetta Stone” style clues. Some scholars even argue it might be a complex symbol system rather than a full writing system, though that’s debated. The result is a strange silence: we can see their cities, touch their everyday objects, and measure their trade networks, but we can’t hear their voices. Those tiny seals are like locked USB drives from a vanished world, sitting in our hands while we fumble for the password.

The Nazca Lines: Giant Figures Only Visible From Above

In the desert plains of southern Peru, the Nazca people created enormous geoglyphs between roughly two thousand and fifteen hundred years ago. These include straight lines stretching for kilometers, complex geometric shapes, and huge figures of animals and plants etched into the ground. From the ground, many of them are hard to see in full, but from the air they form clear patterns, which has fed wild theories about ancient pilots or messages to visitors from the sky.

Archaeologists point out that you can see the designs from nearby hills and that building them did not require flight, just careful planning and coordination. The lines likely had ceremonial or astronomical significance, woven into religious and social life rather than serving any technological purpose. Still, walking across that desert and knowing people patiently laid out these massive patterns without modern surveying tools is humbling. They challenge our habit of assuming that “primitive” automatically means small-scale or simple in imagination.

The Shroud of Turin: Relic, Icon, or Medieval Masterpiece?

The Shroud of Turin is a linen cloth bearing the faint image of a man who appears to have been crucified, preserved in Turin, Italy. Many believers see it as the burial shroud of Jesus, which would obviously have enormous historical and religious implications. Radiocarbon tests done in the late twentieth century dated the cloth to the medieval period, suggesting it is a later creation, but debates over sampling, contamination, and methodology refuse to die down.

What keeps the shroud in the “unexplained” category is not a clear-cut miracle but a stack of technical puzzles. The exact process by which the image was formed is still not firmly settled, even though there are plausible artistic and chemical explanations. The cloth has become a litmus test for how people approach evidence: some see enough doubt in the dating to keep belief alive, while others see a powerful medieval object lesson in how relics were created and revered. Either way, it shows how a single artifact can sit right on the boundary between faith, science, and historical investigation, refusing to let any one side fully claim it.

The London Hammer: Out-of-Place Tool or Misread Rock?

In the 1930s in Texas, a hammer encased in a chunk of stone was discovered and later became infamous in fringe circles as an “out-of-place artifact.” The story goes that the rock around the hammer is extremely old, supposedly hundreds of millions of years, while the hammer itself looks modern and iron-headed, implying impossible timelines. On the surface, it sounds like a direct punch to standard geology and archaeology.

Geologists, however, have explained that the stone surrounding the hammer is more likely a type of relatively young concretion, where minerals precipitated around a modern object, hardening into a rock-like mass. From that perspective, the hammer is an ordinary nineteenth-century tool that happened to be preserved in an unusual way. The real lesson here is how easy it is to confuse “looks ancient” with “is ancient,” especially when we want a dramatic story. Even if the London Hammer doesn’t rewrite history, it shows how powerful our urge is to find cracks in the official story, and how important it is to separate curiosity from wishful thinking.

Pleistocene Cave Art: Advanced Minds in the Deep Past

When you stand in front of Ice Age cave paintings in places like Chauvet or Lascaux in France, or in the caves of northern Spain, the sophistication hits hard. These images of animals, abstract symbols, and hand stencils are tens of thousands of years old, some pushing back well beyond thirty thousand years. Yet the shading, movement, and composition feel shockingly modern, as if someone from our time had just finished them and stepped out for air.

For a long time, popular culture treated our distant ancestors as dull, half-animal figures stumbling toward intelligence. The art buried deep in these caves shatters that stereotype. It shows that by the time these paintings were made, humans already had advanced symbolic thinking, complex social lives, and a sense of beauty and narrative. It doesn’t suggest lost high-tech civilizations, but it does hint that our mental world – the world of imagination, myth, and meaning – is far older and richer than the spare bones and tools in textbooks used to imply.

A Messier, More Interesting Human Story

When you put these artifacts side by side, a pattern starts to form. It is not a neat conspiracy pointing to one grand hidden civilization, but a more human pattern of brilliance, loss, reinvention, and forgotten experiments. Tools and texts vanish, skills get rediscovered centuries later, and every now and then we dig something up that forces experts to admit, with varying degrees of discomfort, that the picture is still incomplete.

For me, that’s the real magic of these mysteries: they keep us honest. They remind us that history is not a finished script but a draft covered in eraser marks, where each new find can nudge a line or redraw an entire act. The unanswered questions around these artifacts are not a failure of science or archaeology; they’re the fuel that keeps those fields alive and searching. If a handful of strange objects can shake our confidence in what we “know,” what else might still be buried, waiting to nudge the story of us in a completely new direction?