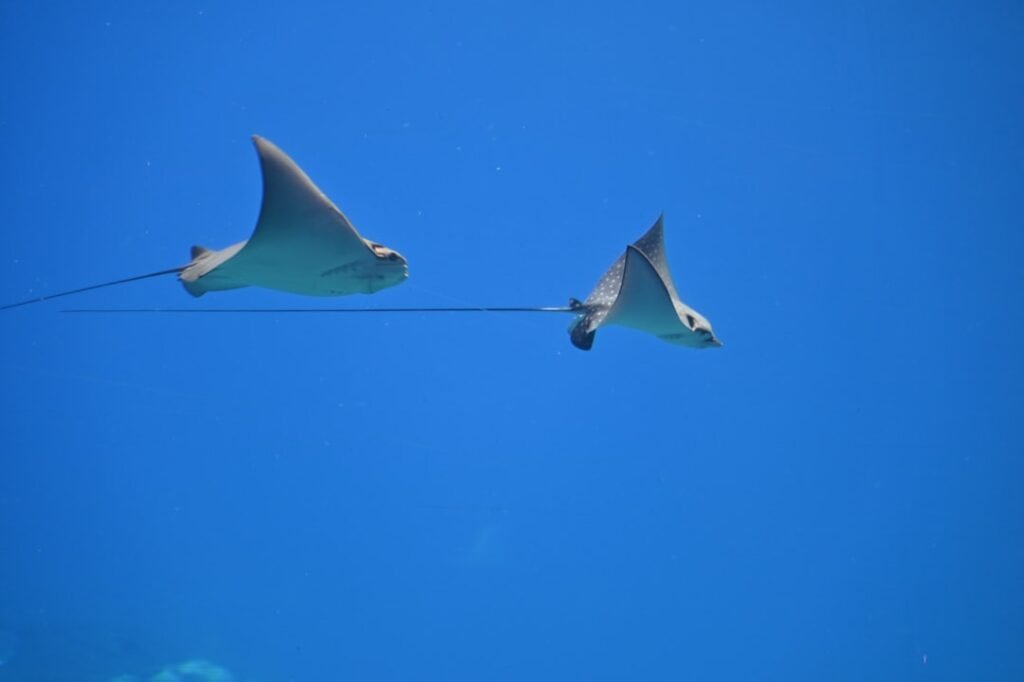

Stingrays Evade Trackers No More (Image Credits: Unsplash)

Researchers overcame decades of frustration by developing a secure multisensor tag for stingrays, creatures that had long defied traditional biologging efforts.[1][2]

Stingrays Evade Trackers No More

Powerful swimmers in turbulent waters, stingrays presented unique hurdles for scientists. Their ultra-smooth skin offered no grip, and the absence of prominent dorsal fins eliminated standard attachment points used successfully on sharks, whales, and dolphins.[1]

A team led by Cecilia M. Hampton and Matthew J. Ajemian at Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute tackled these issues head-on. They designed a tag that clung fast during high-energy maneuvers, achieving attachment durations up to 59 hours – the longest recorded for external tags on such pelagic rays.[2] Spiracle straps and silicone suction cups ensured stability, even as rays powered through strong currents. This innovation marked the first multi-sensor deployment on durophagous stingrays, species that crush hard-shelled prey like clams and conch.

Crafting a High-Tech Spy Device

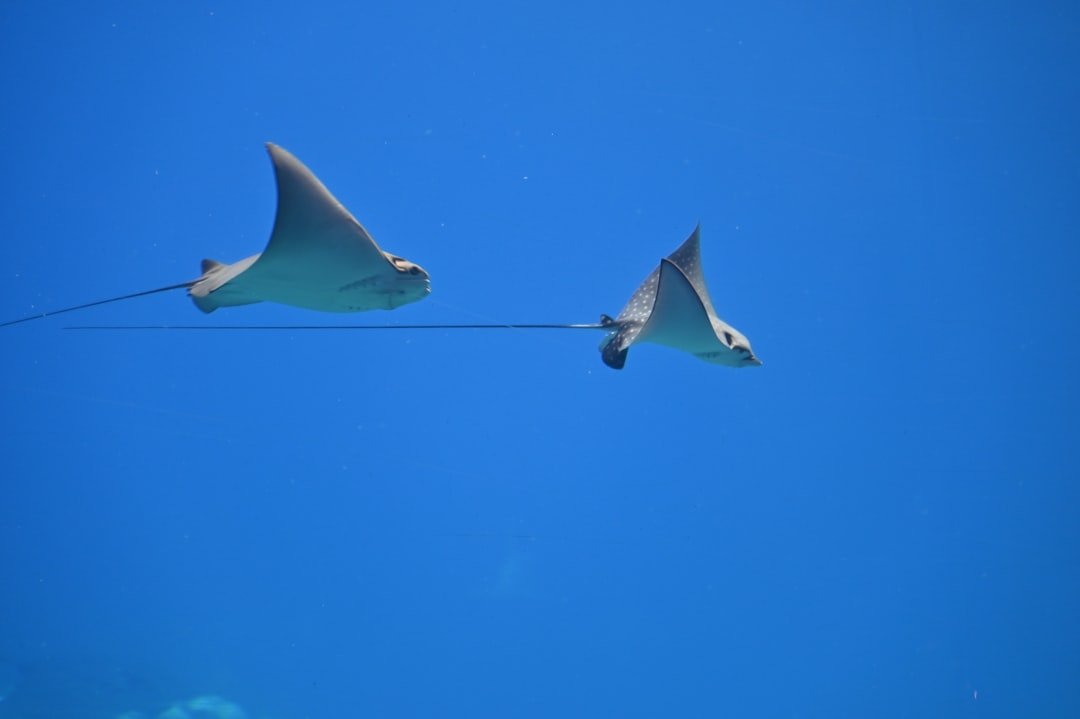

The custom tag packed advanced sensors into a lightweight package tailored for the whitespotted eagle ray, Aetobatus narinari. Deployment took mere seconds: teams dried the skin, pressed suction cups onto the anterior dorsal region, and secured straps around the spiracles – small openings behind the eyes.[1]

Key components included:

- Motion sensors (accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer) sampling at high frequencies to detect pitching and postural shifts.

- A video camera capturing 1080p footage at 30 frames per second.

- A broadband hydrophone recording underwater sounds up to 22 kHz, picking up shell-crushing cracks.

- Satellite and acoustic transmitters for location tracking.

- Depth, temperature, and light sensors for environmental context.

Galvanic timed releases detached the device after 24 or 48 hours, minimizing disturbance. Captive tests refined the design before field use.[2]

Insights from Bermuda’s Waters

Field trials in Bermuda targeted wild whitespotted eagle rays, large predators with wingspans exceeding two meters. Thirteen deployments yielded over 240 hours of data, revealing behaviors once hidden from view.[2]

Video and audio synced with motion data exposed feeding sequences: rays browsed sediments, dug for prey, then crushed shells with audible snaps. A machine learning model, trained on this footage, classified activities – swimming, browsing, digging – with high accuracy, even sans video. One ray’s 16 feeding events highlighted precise foraging tactics in sand, silt, and reef habitats. “We’re now able to observe not just where these rays go, but how they feed,” Ajemian noted.[1]

These rays, despite migratory tendencies, lingered in coastal lagoons, underscoring their ecological roles.

Boosting Conservation Through Better Data

Batoids like stingrays face extinction risks, yet knowledge gaps hindered protection efforts. The new tag bridges this divide by mapping behavioral patterns and habitat use.

Future applications could extend to other rays, with simplified versions relying on motion and sound alone. Hampton emphasized the potential: “This opens exciting possibilities for long-term ecological monitoring.” Combined data streams and AI promise to turn rays into sentinels of ocean health, tracking benthic changes and species interactions.[1]

Key Takeaways

- First multi-sensor tags stayed attached up to 59 hours on fast-moving stingrays.

- Captured shell-crushing sounds, digging motions, and precise foraging behaviors.

- Paves way for conservation by illuminating roles in marine food webs.

This leap in biologging equips scientists to safeguard these vital predators amid environmental pressures. What behaviors surprise you most in stingrays? Share in the comments.