Imagine standing in a vast, silent cathedral so old that its stones still echo with the first words ever spoken there. That’s what cosmologists are doing when they study the oldest light in the universe: they’re listening to the after-echo of creation itself. This ancient glow, called the cosmic microwave background, is not just a scientific curiosity; it’s a time machine that lets us glimpse the universe as a newborn, long before stars, planets, or galaxies existed.

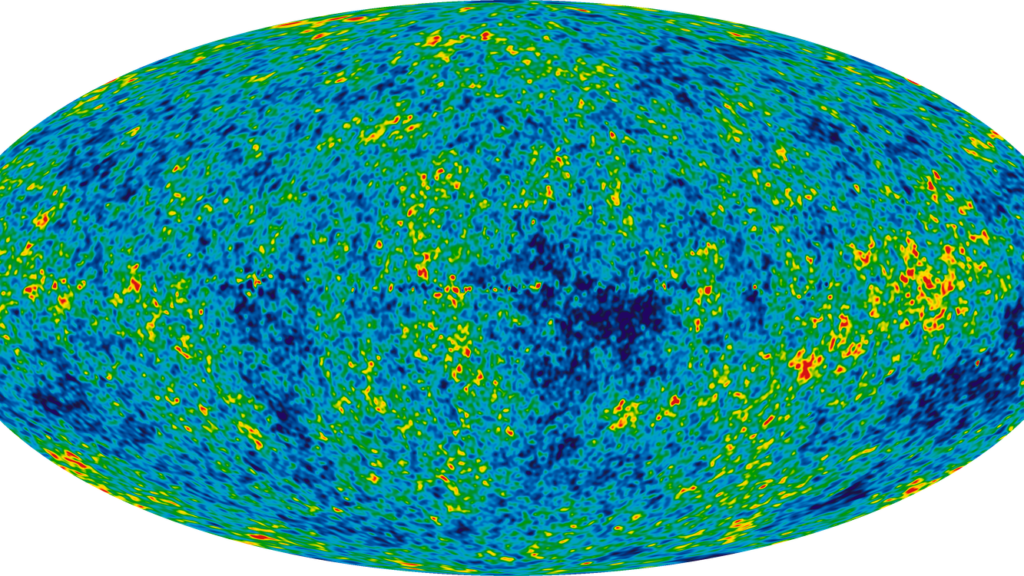

When I first saw a false-color map of this light, I was struck by how ordinary it looked: blotches of blue and red, like a weather forecast. But behind those tiny variations lies the entire story of why there is structure in the universe at all – why matter clumped into galaxies instead of staying a smooth soup. The more we decode this faint radiation, the more it challenges our assumptions about time, space, and what “creation” even means.

The Faint Glow of the Big Bang: What Is the Oldest Light?

The oldest light in the universe is a soft, cold glow that fills all of space, even the emptiest voids between galaxies. It’s called the cosmic microwave background, or CMB, and it’s the afterglow of the hot, dense beginning we usually call the Big Bang. This light was first produced when the universe was only a few hundred thousand years old, long before any star ever shone.

Back then, the cosmos was a glowing fog of particles and light, so hot and dense that photons couldn’t travel far without bumping into electrons. As the universe expanded and cooled, it reached a point where atoms could form and light could finally move freely. That freed light has been racing across space ever since, stretched by the universe’s expansion into microwaves – much cooler, but still carrying a memory of that early epoch.

Looking Back in Time: How We Can See the Baby Universe

When we look at the cosmic microwave background, we’re not just seeing far away; we’re seeing far back in time. Because light takes time to travel, the photons that hit our telescopes today started their journey almost thirteen and a half billion years ago. In a very real sense, the night sky is a history book, and the CMB is the oldest chapter we can still read directly.

Telescopes like COBE, WMAP, and Planck have mapped this ancient glow in astonishing detail, turning faint radio-like signals into full-sky images. At first glance, those images look nearly uniform, the same temperature in every direction. But on closer inspection, tiny temperature differences – thousands of a degree – reveal a detailed imprint of what the universe looked like when it was just a cosmic infant.

Frozen Ripples: Tiny Fluctuations That Built Everything

The most surprising thing about the oldest light is that it’s not perfectly smooth. Instead, it’s sprinkled with tiny hot and cold spots, slight ripples in density and temperature. These fluctuations were incredibly small at first, but over billions of years they grew into the cosmic web of galaxies, clusters, and voids we see today. In other words, those faint blotches in the CMB are the seeds of everything: stars, planets, and even us.

These ripples work a bit like sound waves frozen in time. In the early universe, matter and light were locked together, sloshing and vibrating under the tug-of-war between gravity and pressure, much like vibrations in a drum skin. When the universe cooled enough for light to decouple, that motion suddenly stopped, leaving behind a snapshot of the waves at that exact moment. The pattern of those “frozen” ripples is encoded in the CMB and can be read like sheet music by cosmologists.

Weighing the Cosmos: What the Light Reveals About Matter and Dark Stuff

By studying the pattern of hot and cold spots in the CMB, scientists can measure what the universe is made of with surprising precision. The size and distribution of the ripples act like a cosmic fingerprint that depends on how much normal matter, dark matter, and dark energy the universe contains. It turns out that normal matter – the stuff that makes stars, planets, and people – accounts for only a small fraction of the total. The rest is the invisible dark components that don’t emit light but shape the universe’s fate.

This might sound abstract, but it’s a bit like listening to the sound of a bell and figuring out what it’s made of and how thick it is. The CMB “ringing” tells us that dark matter was already influencing how matter clumped together in the early universe, even though we still don’t know exactly what dark matter is. The same data also reveal that some mysterious form of dark energy is pushing space to expand faster over time, hinting that the universe’s story won’t be a simple fade-out but something stranger.

Cosmic Birth Pains: Clues About Inflation and the Very First Fraction of a Second

The CMB doesn’t just tell us what happened hundreds of thousands of years after the Big Bang; it also whispers about what might have happened in the first unimaginable split-second. The smoothness of the CMB across the sky, combined with its specific pattern of fluctuations, strongly suggests that the universe went through a brief, blisteringly fast growth spurt called inflation. During this phase, space itself is thought to have expanded faster than light, ironing out irregularities and stretching tiny quantum jitters into the seeds of galaxies.

This idea sounds wild, but the CMB’s detailed features – how strong the fluctuations are on different scales – fit the predictions of inflation remarkably well. Cosmologists are still hunting for more direct signs of this early burst, such as subtle polarization patterns in the CMB that could be fingerprints of primordial gravitational waves. If those patterns are ever seen clearly and confirmed, they would be direct evidence that the universe’s birth was even more dramatic than the standard Big Bang picture suggests.

The Universe’s Age and Shape: Geometry Written in Light

The CMB also tells us how old the universe is and what shape it has on the largest scales. By comparing the apparent size of certain features in the CMB with how big they should physically be, scientists can infer how much space has stretched since that light was emitted. This comparison gives an age for the universe of about thirteen and a half billion years, with only a small uncertainty, making the CMB a kind of cosmic birth certificate.

Just as importantly, the data show that the universe is incredibly close to geometrically flat, meaning that parallel lines would stay parallel over cosmic distances. This might sound abstract, but it sets strong constraints on how much matter and energy the universe can contain and still match what we see. The fact that our universe seems so finely balanced between open and closed has led many researchers to wonder whether inflation or deeper physics tuned these conditions in the earliest moments.

Cracks in the Story: Tensions, Anomalies, and What We Still Don’t Understand

For all its success, the picture drawn from the oldest light is not perfectly comfortable. There are puzzling tensions and oddities that refuse to go away, sparking fierce debates among cosmologists. One of the most famous is the disagreement between how fast the universe seems to be expanding today when measured from nearby objects, and the rate inferred from CMB data. The two methods give different answers, and the gap is large enough that many researchers suspect new physics might be lurking behind it.

There are also strange, low-level anomalies in the CMB itself, such as an unusually large cold region and hints of asymmetry between opposite sides of the sky. Each of these could be a fluke, the kind of statistical oddity that appears naturally when you only have one universe to look at. But together, they keep alive the possibility that our standard story of cosmic creation is incomplete, missing a twist we haven’t yet imagined.

What the Oldest Light Tells Us About Our Place in Creation

When you step back from the technical details, the emotional impact of the CMB is hard to ignore. The fact that we can build instruments on a small rocky planet and detect the faded glow of the universe’s childhood is quietly astonishing. That light links us to a moment when there were no stars, no galaxies, and certainly no life, only a hot, almost featureless sea of particles and radiation. Yet hidden in that near-uniformity were the tiny imperfections that made everything complex and beautiful possible.

The oldest light doesn’t answer every question about why the universe exists, or what, if anything, came “before” the Big Bang. But it strips away any illusion that creation was neat, simple, or immediately understandable. Instead, it shows us a cosmos that is finely structured, governed by deep laws, and still full of mysteries that honest science cannot yet resolve. In listening to this faint afterglow, we’re not just studying the universe’s earliest moments; we’re confronting the fact that our own existence traces back to those delicate ripples in a newborn cosmos.