Every few years, a new fossil, a strange tool, or a buried footprint quietly blows up everything we thought we knew about our own story. Timelines shift, old assumptions crumble, and suddenly the map of human history looks completely different. It’s a bit like discovering extra chapters in a book you thought you’d finished years ago.

What’s wild is how many of these breakthroughs weren’t found with high-tech labs at first, but by people stumbling over bones on a walk, or by construction crews digging foundations. From mysterious ancient cousins to the first artists and sailors, early humans keep surprising us. Here are ten discoveries that genuinely rewired our understanding of who we are and where we came from.

The Taung Child and the Discovery of Early Hominins in Africa

Almost a century ago, a small fossil skull from Taung in South Africa shocked researchers by hinting that human origins might lie in Africa rather than Europe or Asia. This fossil, belonging to a species now called Australopithecus africanus, showed a mix of ape-like and human-like traits, especially in its teeth and the position of the skull’s opening for the spinal cord. It looked like a creature that still climbed trees but also walked upright.

At the time, many scientists assumed that big brains came first and that Europe was the cradle of humankind. The Taung Child helped flip that script, suggesting that walking upright evolved before large brains and that Africa was the likely homeland of the earliest human relatives. Since then, thousands of fossils across East and South Africa have backed this up. Today, the idea that our deep roots are African is one of the most solid pillars in human evolutionary science.

Lucy and the Revelations of Australopithecus afarensis

In the 1970s, the discovery of an unusually complete skeleton in Ethiopia – nicknamed Lucy – gave researchers an almost eerie window into a being who lived more than three million years ago. Lucy was small, with long arms and a brain closer in size to a chimp’s than to a modern human’s. Yet her pelvis, leg bones, and the angle of her knee made one thing clear: she walked upright on two legs.

Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis, showed that our ancestors were walking like us long before they looked like us in the face or had our mental horsepower. It shattered the comforting idea that big brains led the way and everything else followed. Instead, walking on two feet may have been the early gamble that eventually opened doors to tool use, long-distance travel, and new ways of surviving. For many people, seeing Lucy’s bones in a museum is like looking at a ghost from a world that was almost-but-not-quite human.

Homo habilis and the Emergence of the First Stone Tools

When simple stone tools were first found in Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, they looked like little more than sharp rocks. But they represented a massive mental leap: the decision to shape the environment intentionally, rather than just accept what nature provided. These early tools, often tied to a species named Homo habilis, changed the way our ancestors accessed food, letting them slice meat, crack bones for marrow, and process plants.

Homo habilis was smaller and more primitive than later members of the human family, yet those rough flakes and cores are some of the earliest clear signatures of human-like thinking. They pushed scientists to recognize that intelligence is not just about brain size, but how that brain is used. The discovery of these tools and their association with early Homo showed that technological creativity began earlier, and with humbler-looking beings, than anyone had expected.

Homo erectus and the Epic of Early Human Migration

The species known as Homo erectus turned out to be a kind of Iron Age hero in a Stone Age world. First recognized from fossils in Java and China, and later from Africa and beyond, Homo erectus had a larger brain, longer legs, and a body built for distance walking. Evidence shows that this species spread out of Africa into Asia and possibly parts of Europe more than a million years ago, making them the first known global travelers in our lineage.

Their tools became more refined, with symmetrical handaxes that required planning and skill to produce. Many researchers think Homo erectus may have mastered fire at least in some regions, which would have been a game-changer for warmth, protection, and cooking. Discoveries of their fossils across vast distances forced scientists to abandon the idea that early humans were timid, local creatures. Instead, our ancestors were restless explorers far earlier than many had guessed.

The Flores “Hobbits” and the Surprise of Island Dwarfism

When tiny human-like bones were uncovered on the Indonesian island of Flores in the early 2000s, they caused an uproar. This species, later named Homo floresiensis, stood barely over a meter tall, with a small brain roughly the size of a grapefruit. Yet they seemed to have made stone tools and hunted animals. They looked like characters out of a fantasy novel, but their reality was backed by solid bones and dates.

The biggest shock was that these “hobbits” appear to have survived until relatively recent times on an evolutionary scale, long after modern humans had spread widely. Their small size fits with a known pattern called island dwarfism, where large animals get smaller over generations when isolated on islands with limited resources. The Flores discovery proved that human evolution produced more strange side branches than anyone imagined, and that our world once held multiple, very different kinds of humans living in parallel.

The Denisovans and the Genetic Ghosts in Our DNA

In a cave in Siberia, a small finger bone and a few teeth were all it took to reveal an entire unknown branch of the human family. Genetic analysis showed that these remains came from a population now called Denisovans, neither Neanderthal nor modern human, but a sister group that split off hundreds of thousands of years ago. There were no famous skulls, no classic skeletons – just fragments and powerful DNA sequencing.

The real shock came when scientists compared Denisovan DNA to living people. Populations in parts of Asia, Oceania, and the Americas carry small but meaningful traces of Denisovan ancestry, evidence of ancient interbreeding. Some of these genes seem to help with high-altitude adaptation or immune responses. It was the scientific version of learning that an entire branch of distant cousins existed, had children with your ancestors, and then vanished, leaving only faint genetic fingerprints behind.

Neanderthals Reimagined: From Brutes to Sophisticated Relatives

For a long time, Neanderthals were the butt of the joke: portrayed as clumsy, dim-witted cavemen who were simply outcompeted by smarter modern humans. But discoveries over the past few decades have wrecked that stereotype. Archaeological sites show Neanderthals using complex tools, controlling fire, and likely caring for injured or elderly group members. They buried their dead in some places and may have used pigments and ornaments, hinting at symbolic behavior.

Genetic studies added another twist: many people alive today, especially outside of Africa, carry a small fraction of Neanderthal DNA. That means our ancestors did not just replace them; they mixed with them. This changed Neanderthals from evolutionary losers into part of our extended family history. The image that emerges now is of a smart, resilient cousin who survived harsh Ice Age environments for hundreds of thousands of years, and whose legacy still literally runs in our veins.

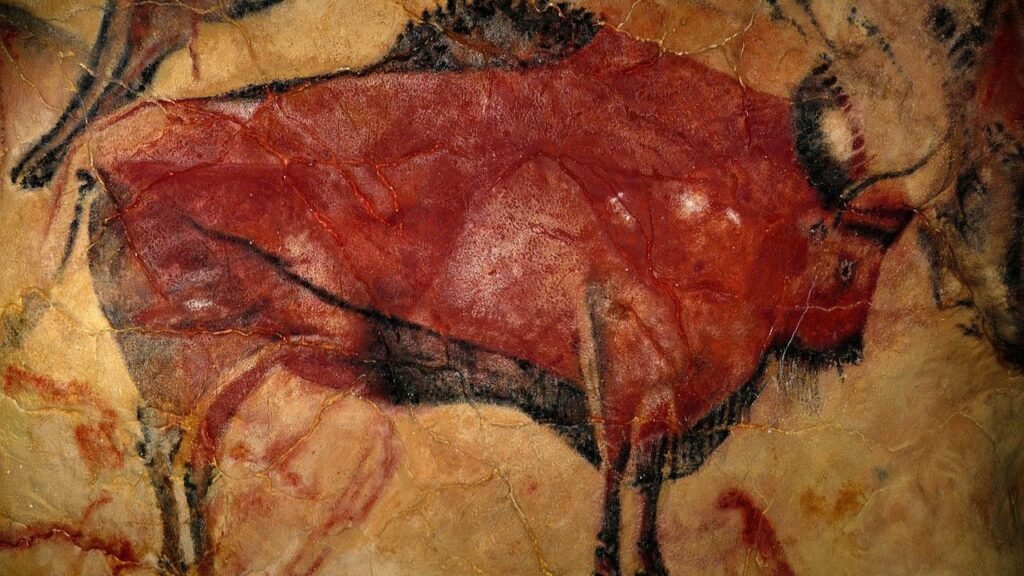

The Oldest Known Art: Cave Paintings and Symbolic Minds

Early humans left more than bones and tools – they also left messages, if we know how to read them. Ancient cave paintings and carvings in places like Europe, Indonesia, and southern Africa show animals, hand stencils, dots, and abstract patterns that may carry symbolic meaning. Some of these artworks are tens of thousands of years old, older than many written languages and most civilizations we learn about in school.

Dating techniques have pushed the origins of cave art further back than many expected, and in some cases suggest that Neanderthals may have created certain markings. That possibility alone challenges the idea that modern humans had a monopoly on imagination. These early artworks reveal that long before cities, empires, or writing, humans were already telling stories, marking territory, and perhaps dreaming out loud on rock walls. The impulse to create and symbolize seems to be as deeply human as walking on two legs.

Some of the oldest personal ornaments – shell beads, engraved pieces of ochre, and decorated bones – also hint at identity and social meaning. Wearing a bead necklace or painting your body with pigment is not about pure survival; it’s about status, belonging, or ritual. Finds like these push us to accept that even very ancient humans were not just surviving day to day, but thinking in symbols, forming cultures, and expressing something beyond the basic needs of food and shelter.

The First Seafarers: Early Humans Crossing Open Water

For a long time, people assumed that complex seafaring was a very recent skill, tied to advanced civilizations with big ships and written navigation. Then archaeologists started finding evidence that early humans reached islands like Australia and parts of Southeast Asia far earlier than anyone thought possible. These crossings would have required some kind of watercraft, because the sea gaps were too wide to simply walk during low sea levels.

This realization dramatically upgraded our view of early human ingenuity. If our ancestors were building boats or rafts tens of thousands of years ago, they were planning ahead, understanding currents and winds at least intuitively, and coordinating group journeys. The idea of ancient humans staring at a visible island across open water and deciding to build something to reach it is incredibly powerful. It suggests curiosity and courage that feel very familiar, even across such a long stretch of time.

Footprints, Fire, and the New Timelines of Human Presence

Sometimes, the most haunting evidence of early humans is not a skull or a spearhead, but a simple footprint. In recent years, tracks preserved in ancient mud and ash layers – from Africa to the Americas – have forced scientists to reconsider when humans or their relatives first appeared in certain regions. Some footprints in North America, for example, have been dated to a time earlier than the widely accepted migration windows, stirring intense debate and fresh research.

Similarly, charred hearths, burned bones, and microscopic ash layers are being re-examined with new techniques to trace the controlled use of fire. Fire is one of the few technologies that changes everything: diet, sleep, safety, even social life around a campfire. These subtle traces, often missed in older excavations, are now reshaping timelines and raising new questions. Each footprint and each ancient fire pit is a quiet reminder that our ancestors were roaming, experimenting, and adapting in ways we are only just beginning to uncover.