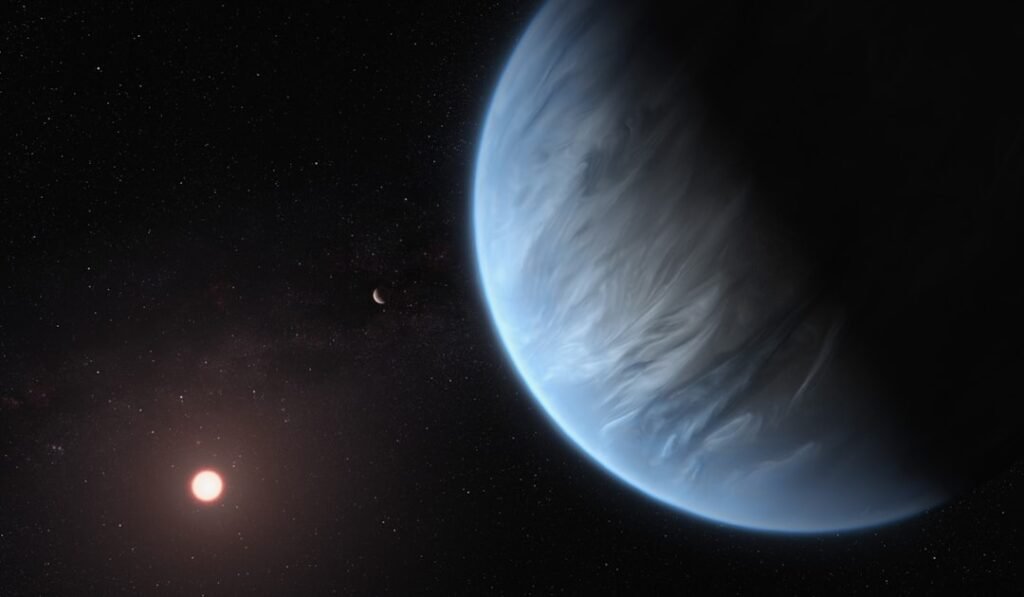

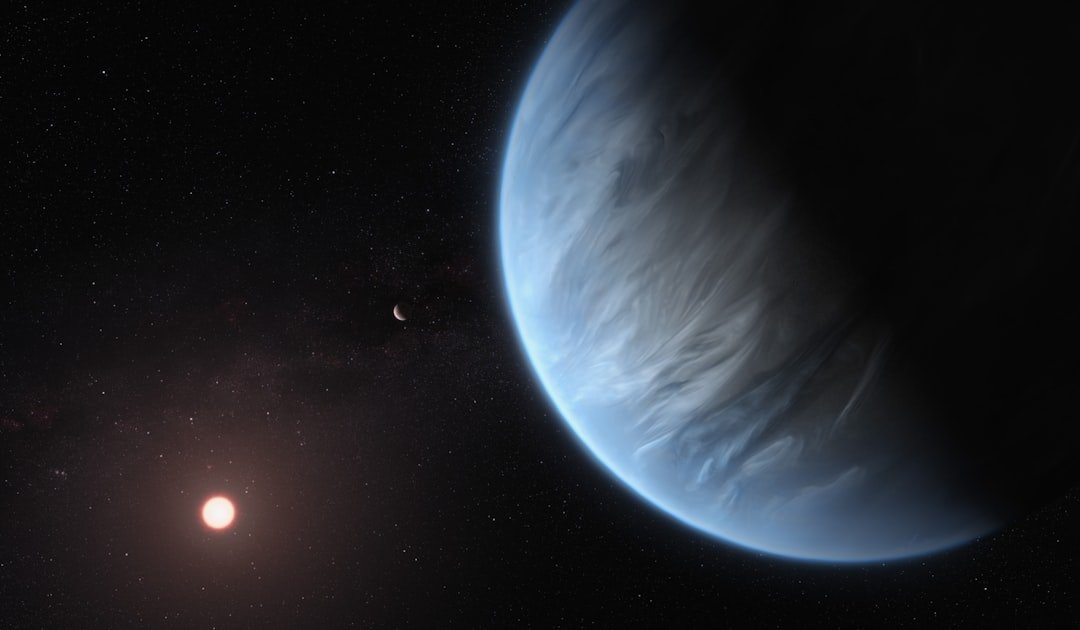

HR 8799: A Prime Window into Giant Planet Birth (Image Credits: Unsplash)

Astronomers have pinpointed sulfur in the atmospheres of massive gas giants around the star HR 8799, offering fresh insights into how these super-Jupiters assembled far from their host star.[1][2]

HR 8799: A Prime Window into Giant Planet Birth

The HR 8799 system stands out as the only known setup where astronomers have directly imaged four massive gas giants. Located 133 light-years away in the constellation Pegasus, this young stellar family clocks in at about 30 million years old.[1] Each planet weighs between five and ten times Jupiter’s mass and circles the star at distances from 15 to 70 astronomical units.

These wide orbits once puzzled researchers. Traditional models predicted that protoplanetary disks would dissipate before solid cores could bulk up enough to snag vast gas envelopes. The James Webb Space Telescope changed that equation with its 2023 observations of the three inner worlds.[2]

Sulfur Emerges as a Key Formation Clue

Sulfur-bearing molecules, such as hydrogen sulfide, appeared clearly in the spectrum of HR 8799 c. Scientists expect the signature graces the other inner giants too. Unlike volatile gases like water vapor, sulfur locks into solid grains during planet formation.[3]

This refractory element hitches rides on pebbles and planetesimals that build planetary cores. Jean-Baptiste Ruffio, a research scientist at the University of California San Diego and lead analyst, noted the breakthrough: “With the detection of sulfur, we are able to infer that the HR 8799 planets likely formed in a similar way to Jupiter despite being five to ten times more massive, which was unexpected.”[2]

Team members crafted new data-processing techniques to tease out the planets’ faint signals – about 10,000 times dimmer than the star. Refined atmospheric models then confirmed the molecular lineup, spotting rare features for the first time in this system.

Core Accretion Prevails in the Debate

Two main theories explain gas giant origins. Core accretion starts small: dust grains clump into pebbles, then planetesimals, forging a dense core that gravity pulls in hydrogen and helium. Gravitational instability, by contrast, sees gas clouds collapse swiftly, much like stars or brown dwarfs.

The HR 8799 data tipped the scales. Planets boast higher levels of heavy elements, including carbon, oxygen, and now sulfur, than their host star. This metal enrichment mirrors Jupiter’s makeup.

- Solid sulfur delivery via disk solids supports core buildup before gas capture.

- Uniform heavy-element patterns across planets align with pebble-accretion efficiency.

- Wide orbits fit updated models where distant icy planetesimals fuel rapid core growth.

- Enrichment exceeds stellar levels, ruling out pure gas-collapse scenarios.

Quinn Konopacky, a UC San Diego professor and co-author, emphasized the shift: older core-accretion ideas fell short, but newer versions explain distant giants like these.[1]

What Limits a Planet’s Mass?

These findings stretch core accretion’s reach to super-Jupiters. They challenge the fuzzy line between planets and brown dwarfs, prompting questions about objects up to 30 Jupiter masses.

HR 8799’s uniqueness – four imaged giants – makes it invaluable. Techniques honed here will probe other systems with even bulkier companions. Michael Meyer, a University of Michigan astronomer and co-author, declared: “The empirical answer is in. These gas giants formed through core-accretion. It’s a bottom-up process.”[4]

Key Takeaways

- Sulfur detection confirms core accretion for 5–10 Jupiter-mass planets at 15–70 AU.

- Heavy-element surplus echoes solar system’s giants, defying prior disk-lifetime limits.

- JWST spectroscopy sets new benchmarks for tracing exoplanet assembly histories.

This discovery redefines how massive worlds take shape, proving planet-building recipes work even in extreme setups. As JWST peers deeper, it promises to map formation pathways across the cosmos. What boundary do you see between planets and failed stars? Share your thoughts in the comments.