Think of our planet as a survivor of cosmic Russian roulette. For billions of years, Earth has been hit repeatedly by disasters so severe they should have ended everything. Yet somehow, life persisted. These weren’t just setbacks or inconveniences; we’re talking about catastrophes that killed nearly everything alive. What’s fascinating is that these brutal filters didn’t just test life, they fundamentally reshaped it. Every mass extinction, every global freeze, every toxic atmospheric upheaval forced the survivors down new evolutionary paths. Looking back, you start to realize something unnerving: maybe we only exist because previous versions of Earth repeatedly failed. So let’s dive into the planet’s greatest filters and discover how close we’ve come to never existing at all.

The Oxygen Catastrophe: When Life Nearly Poisoned Itself to Death

Around 2.7 billion years ago, a peculiar group of microbes called cyanobacteria evolved the ability to perform photosynthesis, producing oxygen as a waste product. Here’s the thing: to nearly all other life at the time, oxygen was pure poison. Most of the bacteria thriving on Earth were anaerobic, literally metabolizing their food without oxygen. Imagine a world where the very air you need to survive is being slowly replaced by what amounts to toxic waste.

Since life was totally anaerobic 2.7 billion years ago when cyanobacteria evolved, oxygen acted as a poison and wiped out much of anaerobic life, creating an extinction event. Isotope geochemistry data from sulfate minerals have been interpreted to indicate a decrease in the size of the biosphere of more than 80 percent associated with these changes. This wasn’t some gradual adjustment; it was biological warfare on a planetary scale. The dominant life forms watched helplessly as their entire world became uninhabitable, killed by pollution from upstart oxygen producers. Yet those who survived this Great Oxidation Event would eventually give rise to all complex life on Earth, including us.

The Permian Extinction: When Nearly Everything Died

If you want to understand what apocalypse really looks like, study the end of the Permian period. Approximately 251.9 million years ago, Earth experienced its most severe known extinction event, with the extinction of 81% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species. Scientists call it the Great Dying, which is honestly underselling it. Over about 60,000 years, 96 percent of all marine species and about three of every four species on land died out.

The scientific consensus is that the main cause was flood basalt volcanic eruptions that created the Siberian Traps, releasing sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide, resulting in oxygen-starved, sulfurous oceans, elevated global temperatures, and acidified oceans. The sheer scale defies imagination. In the million years after the event, seawater and soil temperatures rose between 25 to 34 degrees Fahrenheit, with sea surface temperatures at the Equator reaching as high as 104 degrees Fahrenheit. This wasn’t just a bad century; it was hell on Earth. The world’s forests vanished completely, and it took roughly ten million years for them to return in force.

Snowball Earth: The Planet’s Near-Total Deep Freeze

Picture this: you’re looking at Earth from space, but instead of blue oceans and green continents, you see nothing but ice. White everywhere. More than 600 million years ago, the planet was frozen from pole to pole, covered in half-kilometer-thick ice sheets that darkened every ocean. This happened not once, but multiple times during what scientists aptly call the Cryogenian period. It sounds like something that should have ended all life permanently.

How sea life clung on during Snowball Earth has long been a mystery. Recent evidence suggests some remarkable survival strategies. Oxygen-rich marine environments existed closest to ice sheets, possibly because meltwater from the base of ice sheets, enriched with oxygen from trapped air bubbles, created vital oxygen oases needed for emerging complex life forms to survive. Life found a way to persist in the most unlikely refuges: meltwater ponds on ice surfaces, near hydrothermal vents, or in thin zones of oxygenated water beneath glaciers. Honestly, it’s hard to say for sure how they made it through, but the fact that you’re reading this proves they did.

The Ordovician-Silurian Extinction: When the Ice Came and Went

Occurring about 443.8 million years ago, the Ordovician-Silurian extinction was the first major mass extinction event, concluding the Ordovician Period, which is known for a dramatic increase in marine life. What makes this filter particularly nasty is the one-two punch it delivered. Scientists think it was caused by temperatures plummeting and huge glaciers forming, which caused sea levels to drop dramatically, followed by a period of rapid warming.

Many small marine species died out during this climate whiplash. Let’s be real: most life at this time lived in the oceans, so when sea levels dropped dramatically and temperatures went haywire, creatures had nowhere to hide. The rapid environmental changes didn’t give species time to adapt. First they froze, then they cooked. Those shallow-water habitats that teemed with life suddenly became death traps as the seas drained away.

The Late Devonian Crisis: Death in Multiple Waves

Starting 383 million years ago, this extinction event eliminated about 75 percent of all species on Earth over a span of roughly 20 million years. Unlike a single catastrophic blow, the Late Devonian extinction came in pulses, making it particularly insidious. In several pulses across the Devonian, ocean oxygen levels dropped precipitously, dealing serious blows to conodonts and ancient shelled relatives of squid and octopuses.

Multiple causes conspired to create this prolonged crisis. Volcanism is a possible trigger: the Viluy Traps erupted 240,000 cubic miles of lava in what is now Siberia, spewing greenhouse gases and sulfur dioxide, which can cause acid rain. Interestingly, land plants may have been accessories to the crime, as plants developed lignin and vascular structures, allowing their roots to get deeper than ever before, which would have increased the rate of rock weathering. So life itself helped trigger its own near-destruction. The irony is almost poetic.

The End-Triassic Catastrophe: Prelude to the Dinosaur Era

About 200 million years ago, Earth experienced its fourth major mass extinction event, triggered by a dramatic rise in greenhouse gases due to volcanic activity, leading to rapid global warming and launching the Jurassic. This event cleared the ecological stage for dinosaurs to dominate, though that wasn’t obvious at the time. In the oceans, nearly 71% of genera vanished, while on land, a staggering 96% of terrestrial genera went extinct, dramatically reshaping the landscape of life.

What’s striking about this extinction is the difference between how marine and terrestrial ecosystems responded. Despite massive loss in the oceans, the overall structure of marine ecosystems showed resilience, with predators like sharks and filter feeders eventually bouncing back. Land, however, was absolutely devastated. The survivors included early dinosaurs and various small predators that would eventually dominate the Mesozoic. Sometimes you don’t win by being the strongest; you win by simply being the last one standing when the dust settles.

The Great Filter Concept: Are We Through the Worst?

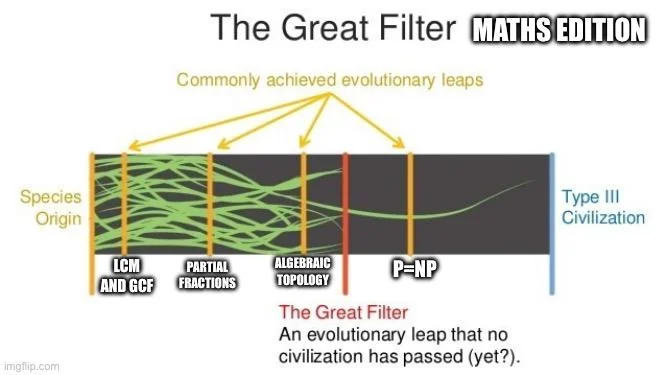

The concept, introduced by Robin Hanson, suggests that the failure to find any extraterrestrial civilizations implies something acts as a Great Filter to reduce sites where intelligent life might arise, a probability threshold that might work as a barrier to evolution or as a high probability of self-destruction. This idea connects Earth’s catastrophic history to a cosmic question: if conditions for life seem common in the universe, where is everybody?

The Great Filter theory says that at some point from pre-life to advanced intelligence, there’s a wall that all or nearly all attempts at life hit, some stage that is extremely unlikely or impossible for life to get beyond. Here’s where it gets uncomfortable: Depending on where the Great Filter occurs, we’re left with three possible realities: we’re rare, we’re first, or we’re in serious trouble. Maybe Earth’s repeated catastrophes were our Great Filters, already passed. Or maybe the real filter lies ahead, waiting for technological civilizations to inevitably destroy themselves. Mass extinctions have sometimes accelerated the evolution of life on Earth, with dominance passing from one group to another because an extinction event eliminates the old group and makes way for the new through adaptive radiation.

Conclusion

Earth’s history reads like a survival manual written in catastrophe. Each filter we’ve explored represents a moment when our planet’s biological experiment nearly ended. The oxygen that we breathe today once killed most life on Earth. The ice that nearly encased our planet should have made complex life impossible. The volcanic eruptions that repeatedly poisoned atmospheres and oceans should have been final.

Yet here we are. Every species alive today descended from survivors who squeezed through impossibly narrow bottlenecks. We exist because countless generations refused to go extinct, adapting to hellish conditions that would make modern climate disasters look tame by comparison. The question that should keep you up at night: have we already passed through our species’ great filter, or is it still waiting for us ahead? Did you ever consider that our existence might be the result of Earth failing catastrophically, over and over, until something finally worked?