Have you ever wondered why certain languages have endured for thousands of years while countless others have simply disappeared? It’s a question that touches something deep about human survival, culture, and identity. Languages are living things in a way, breathing and adapting alongside the communities that speak them. Some manage to weather every storm history throws at them. Others fade quietly, leaving barely a whisper behind.

The story of why languages survive or perish isn’t just about words and grammar. It’s about power, geography, community bonds, and the relentless march of time. Understanding what makes a language immortal, or what condemns it to oblivion, offers us insight into how human societies function and what we stand to lose when linguistic diversity crumbles. So let’s dive in.

The Power of Numbers and Territory

You might be surprised to learn that over half the world’s languages are spoken by fewer than ten thousand people. When a language has only a handful of speakers scattered across a small geographic area, its vulnerability skyrockets. Think of it this way: if a natural disaster strikes or a community migrates, those few remaining speakers might never pass the language to the next generation.

Languages with larger speaker populations and expansive territories have a cushion against catastrophe. Greek boasts the oldest surviving spoken language with an unbroken tradition, spanning over three thousand four hundred years. That continuity didn’t happen by accident. It happened because millions of people across multiple regions kept speaking it, writing it, and teaching it to their children through empires rising and falling.

Economic Incentives That Tip the Balance

Let’s be real: money talks, and it speaks in dominant languages. When speakers seek to learn a more prestigious language to gain social and economic advantages or to avoid discrimination, they often abandon their traditional tongues. If you need to speak English or Mandarin to get a decent job, access healthcare, or participate in the digital economy, you’re going to prioritize those languages over your ancestral one.

Language shifts driven by economic growth and globalization represent the major underlying process of recent speaker declines, rather than the loss of speaker populations themselves. Honestly, it’s hard to blame individuals for making these choices. Yet each time someone decides their native language won’t serve them economically, another thread in the tapestry of human linguistic diversity begins to fray.

Political Forces and Government Policies

Throughout much of the twentieth century, governments across the world imposed language on indigenous people, often through coercion. These weren’t gentle nudges toward bilingualism. We’re talking about policies that separated children from their families, punished them for speaking their mother tongue, and systematically dismantled entire linguistic communities. The scars from these actions still affect language vitality today.

Historical factors that caused dramatic reduction in native speakers, such as massacres of indigenous populations or ethnic groups, punishing people for speaking their language, and separating children from parents, may not be captured in current socioeconomic data. Political recognition matters too. Languages that receive official status, government funding, and inclusion in education systems have far better survival odds than those left to fend for themselves in an increasingly homogenized world.

The Geography of Language Survival

Where you speak a language matters almost as much as how many people speak it. Many small linguistic communities occupy islands or coasts vulnerable to hurricanes or rising sea levels, and the resulting migration causes communities to fragment and greater contact with other languages. Geographic isolation once protected minority languages by limiting contact with dominant ones, yet that same isolation becomes a liability when environmental pressures force migration.

Areas with particularly large numbers of languages nearing extinction include Eastern Siberia, Central Siberia, Northern Australia, Central America, and the Northwest Pacific Plateau. These regions share certain characteristics: they’re often remote, economically marginalized, and populated by indigenous communities facing intense pressure from dominant national cultures. Geography isn’t destiny, but it certainly shapes the battlefield where linguistic survival plays out.

Cultural Transmission and the Critical Role of Children

Here’s the thing: a language truly begins dying when children stop learning it as their first language. When speakers cease to use a language or use it in increasingly reduced domains and cease to pass it on from one generation to the next, there are no new speakers, adults or children. The moment that chain breaks, the language enters what linguists call the extinction debt phase.

Languages currently spoken by adults but not learned as a first language by children will, without active intervention and revitalization, have no more native speakers once the current generation dies. I think this reveals something profound about how languages persist: they need constant renewal through children. Written records help, but without living speakers raising bilingual kids, even extensively documented languages face an uncertain future.

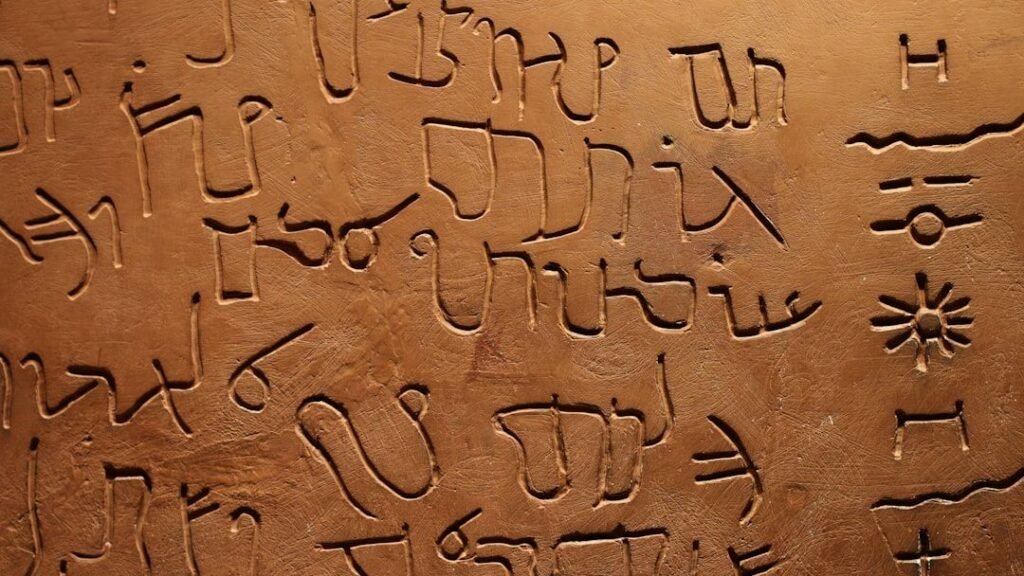

Writing Systems and Documentation

Cuneiform, developed by the Sumerians around three thousand two hundred BCE, lasted for over three thousand years and inspired many early writing systems. The power of writing cannot be overstated when it comes to linguistic persistence. Languages with robust written traditions, extensive literature, and well documented grammar have been successfully revived even after falling out of everyday use.

In rare cases, political will and a thorough written record can resurrect a lost language, as Hebrew was extinct from the fourth century BC to the eighteen hundreds. Yet most endangered languages lack this advantage. They exist primarily in oral traditions, making preservation exponentially harder when speakers dwindle. Still, documentation alone isn’t enough without communities willing and able to reclaim their linguistic heritage.

Globalization and Cultural Homogenization

Languages are currently dying at an accelerated rate because of globalization, mass migration, cultural replacement, imperialism, neocolonialism, and linguicide. The world has never been more connected, and that connectivity comes with linguistic costs. Dominant languages spread through media, technology, and international commerce while minority languages get squeezed into ever smaller spaces.

Climate change and urbanization force linguistically diverse rural and coastal communities to migrate and assimilate to new communities with new languages. When you move to a city where nobody speaks your language, when your children attend schools conducted entirely in the national language, when all the apps and websites use global lingua francas, maintaining your ancestral tongue becomes an uphill battle fought without much institutional support.

The Languages That Endure

So what separates survivors from casualties in this linguistic struggle? Languages like Tamil and Greek have maintained continuous traditions for thousands of years, adapting to changing circumstances without breaking the chain of transmission. They benefit from strong cultural identities, institutional support, vibrant literary traditions, and communities fiercely committed to preservation.

The revival of Hebrew in Israel remains the only example of a language acquiring new first language speakers after becoming extinct in everyday use for an extended period. That success required enormous political will, community mobilization, and favorable conditions rarely replicated elsewhere. Languages persist when communities decide they’re worth the effort, when governments provide support, and when economic circumstances don’t force impossible choices between linguistic heritage and survival. It’s never just about the language itself. It’s about the world we build around it.

Conclusion

The difference between a language that survives millennia and one that vanishes traces back to an intricate web of factors: speaker population size, geographic distribution, economic incentives, political support, cultural transmission patterns, documentation efforts, and community determination. No single factor determines linguistic fate, yet when multiple pressures converge against a language, its prospects darken considerably.

Of the approximately seven thousand documented languages, nearly half are considered endangered, with rates of loss estimated as equivalent to a language lost every one to three months. We’re living through an extinction event, though it unfolds too slowly for most people to notice. Each language that disappears takes with it unique ways of understanding the world, centuries of accumulated knowledge, and irreplaceable cultural treasures. What do you think: can we change course, or is linguistic diversity destined to fade? The answer might depend on choices we make right now, in communities around the globe where the next generation is deciding which languages deserve their voices.