Replicating an Alien Sea (Image Credits: Upload.wikimedia.org)

Scientists recreated the subsurface ocean environment of Saturn’s moon Enceladus in a laboratory setting and observed the spontaneous emergence of diverse organic molecules, bolstering prospects for prebiotic chemistry on this distant world.[1]

Replicating an Alien Sea

A team led by Max Craddock from the Institute of Science Tokyo conducted experiments that mimicked the unique conditions inside Enceladus. They employed a high-pressure reactor to simulate the heating and freezing cycles driven by Saturn’s gravitational pull on the moon’s orbit. These cycles fuel hydrothermal activity similar to Earth’s seafloor vents. The setup incorporated chemicals detected by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, including salts, ammonia, hydrogen, hydrogen cyanide, phosphorus, methane, sodium, potassium, chlorine, and carbonate compounds. Freezing phases in the simulation generated even simpler organics.

Analysis occurred through a laser-based mass spectrometer modeled after Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer. This approach allowed direct comparison with spacecraft data collected from 2005 to 2017. Researchers published their findings in the journal Icarus on January 15, 2026. The study addressed long-standing questions about whether plume organics originated from current ocean processes or ancient formation material.[1]

Organics That Mirror Spacecraft Readings

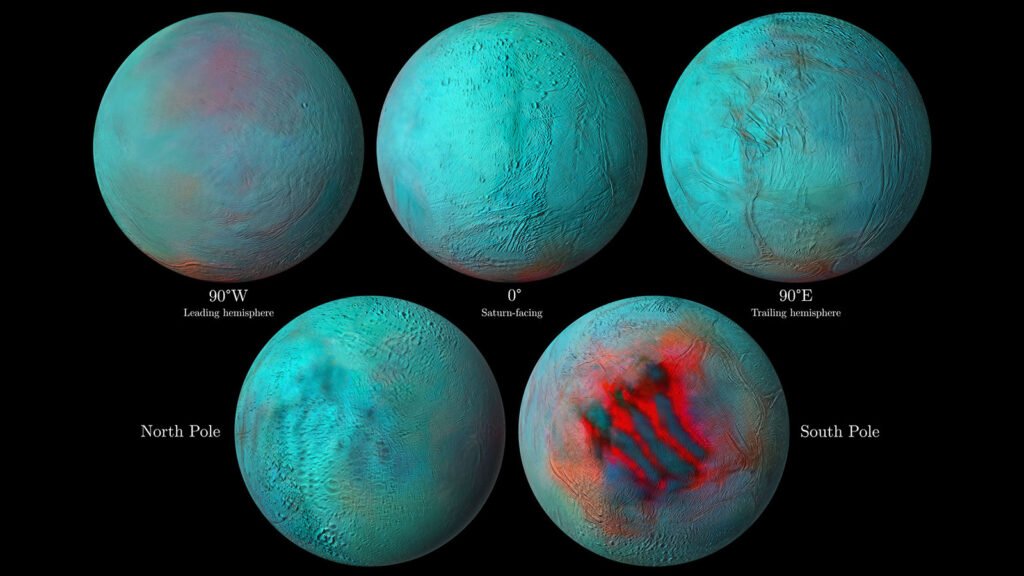

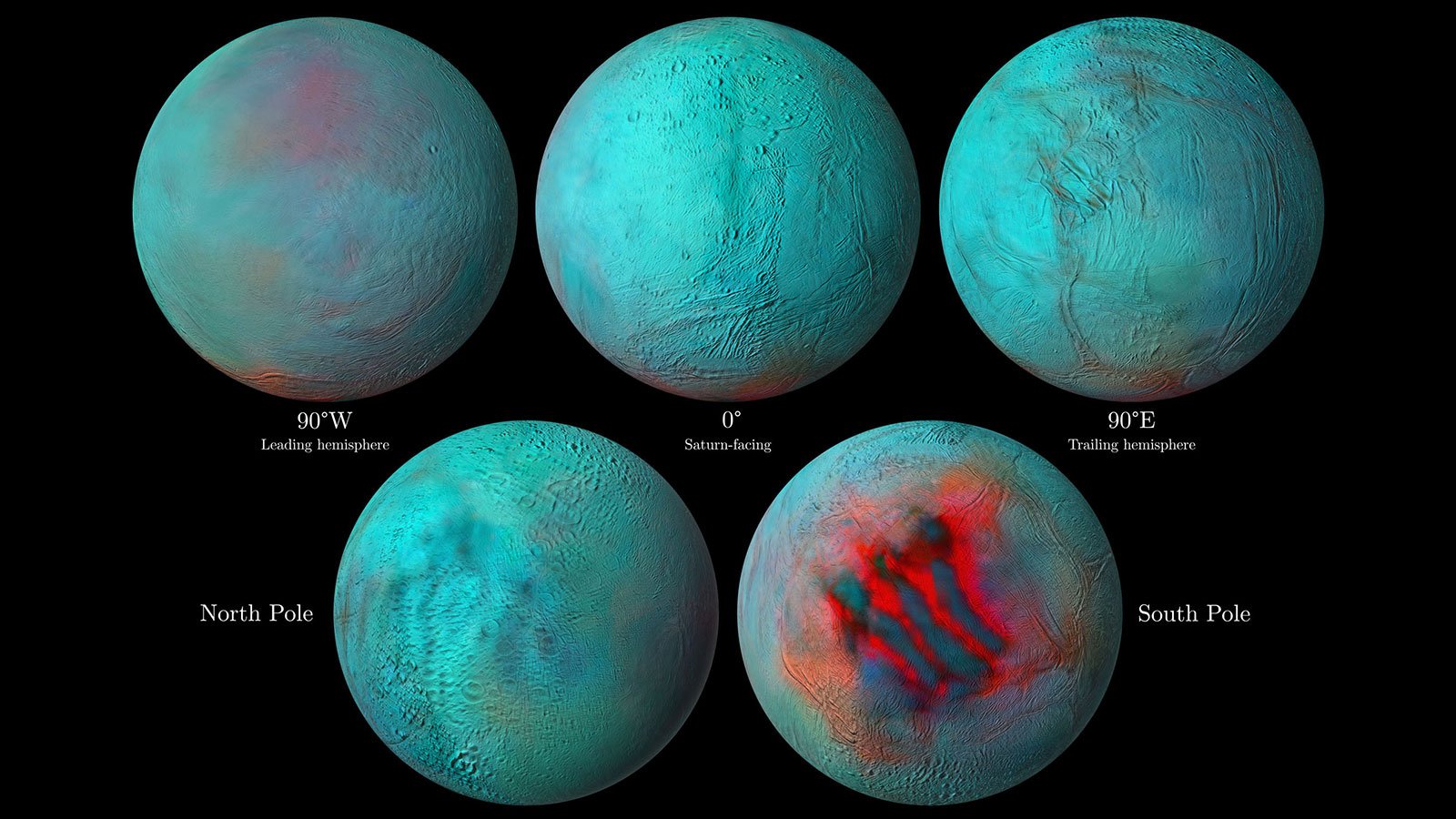

Cassini detected a mix of simple and complex organic compounds in water vapor plumes erupting from cracks at Enceladus’ south pole, known as Tiger Stripes. These plumes draw from the global subsurface ocean beneath the icy crust. The lab simulations produced organics that closely aligned with those observations. Amino acids, aldehydes, and nitriles appeared prominently. Glycine, a basic amino acid, formed during freezing cycles.

However, some larger molecules identified by Cassini did not emerge in the tests. This discrepancy hints at additional chemical pathways or relic compounds from the moon’s past. The results confirmed hydrothermal activity as a key source for many detected organics. Radiation on the surface had been proposed earlier, but evidence now points to subsurface origins.[1]

Essential Ingredients for Life

The experiments highlighted how Enceladus’ ocean fosters the building blocks of life with minimal intervention. Key molecules included:

- Amino acids, fundamental to proteins.

- Aldehydes, precursors in metabolic pathways.

- Nitriles, versatile compounds in organic synthesis.

- Glycine, the simplest amino acid.

- A broad spectrum of complex organics matching plume data.

Such diversity suggests active prebiotic chemistry persists today. Hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor likely drive these reactions. The ocean remains stable enough to sustain such processes over geological time.

Implications for Astrobiology and Future Exploration

Max Craddock noted, “For future missions, this sharpens how plume measurements should be interpreted and underscores the importance of instruments capable of verifying amino acids and resolving whether complex organics reflect ongoing internal chemistry or ancient material.”[1]

The findings elevate Enceladus as a prime target for habitability studies among ocean worlds. Upcoming missions must equip advanced analyzers to detect amino acids in plumes. Distinguishing active chemistry from primordial remnants will clarify life’s potential. Observations like these will guide searches for life beyond Earth. For more details, see the original report on EarthSky.

Key Takeaways

- Lab simulations matched Cassini plume organics, confirming ocean-based synthesis.

- Amino acids and other precursors form readily via hydrothermal cycles.

- Enceladus demands advanced tools on future probes to probe habitability.

These simulations transform our view of Enceladus from a frozen curiosity to a viable laboratory for life’s origins. What do you think about the chances of life on this icy moon? Tell us in the comments.