The Goldilocks Zone Faces Scrutiny (Image Credits: Flickr)

Researchers have begun questioning the narrow confines of the traditional habitable zone in their pursuit of extraterrestrial life.

The Goldilocks Zone Faces Scrutiny

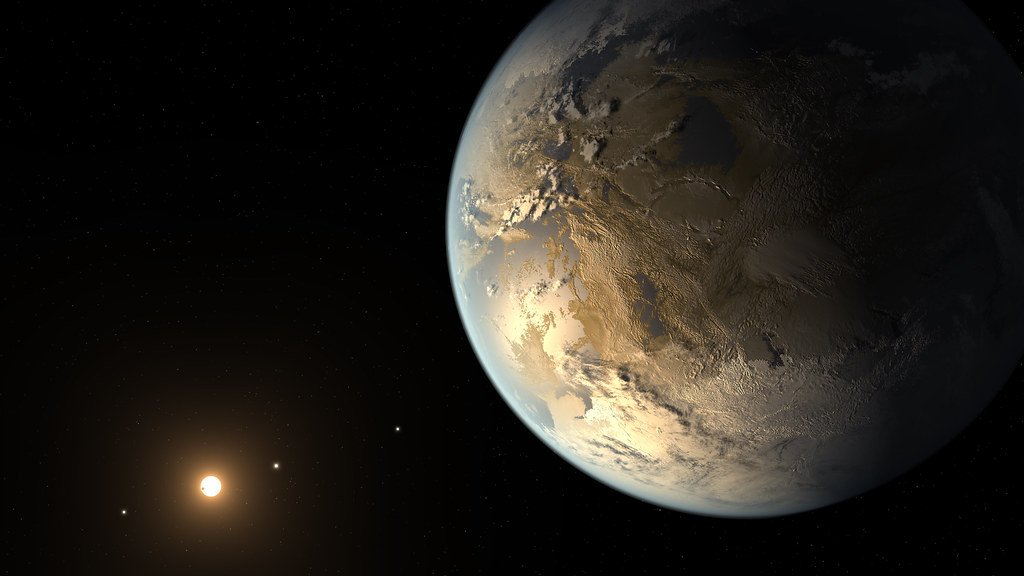

A surprising revelation emerges from advanced climate modeling: planets tidally locked to their stars could harbor liquid water far closer to stellar heat than previously thought.[1]

The classic habitable zone, often dubbed the Goldilocks zone, defines the orbital region around a star where conditions might allow surface liquid water – neither too hot nor too cold. Scientists long relied on this concept to prioritize exoplanet targets. However, a study published on January 12 in the Astrophysical Journal argues that such limits overlook viable worlds.[1]

The paper’s authors used analytical models to show how factors like atmospheric pressure and ocean coverage can redistribute heat effectively. This challenges assumptions about atmospheric collapse on a planet’s dark side. Traditional boundaries fail to account for these dynamics, especially around cooler stars.

Tidally Locked Planets Redefine Boundaries

Tidally locked exoplanets, common around small M-class and K-class stars, rotate so slowly that one side constantly faces their star. Yet, these worlds might sustain liquid water on the perpetual night side, even inside the conventional inner habitable zone edge.

High atmospheric pressure prevents volatiles from freezing out, while oceans facilitate heat transport from the hot dayside. The models predict stable temperatures across vast areas. For rapidly rotating planets, the habitable zone starts farther out, but locked ones extend it inward significantly.

These findings broaden the candidate pool dramatically. Astronomers now consider warmer super-Earths orbiting tight around dim red dwarfs as promising venues for life.

JWST Observations Bolster the Case

The James Webb Space Telescope has detected water vapor and other gases in atmospheres of small exoplanets hugging M dwarf stars – positions once deemed uninhabitable. These detections defy expectations, as intense stellar radiation was thought to strip away water and air. Instead, the planets retain substantial volatiles. Such evidence aligns with model predictions of extended habitability.[1]

Transmission spectroscopy from JWST reveals these surprises, prompting a reevaluation of search strategies.

Earth’s Extremes Point to Hidden Possibilities

Life on our planet thrives in harsh conditions, offering clues for extraterrestrial habitability. Microbial communities flourish in Antarctica’s subglacial lakes, buried under thick ice yet warmed by geothermal heat.

Similar setups could exist on cold exoplanets beyond the outer habitable zone edge. Thick ice shells insulate subsurface oceans, where internal heating or tidal forces maintain liquidity. Surface water proves unnecessary when chemical energy and diverse elements sustain biology.

- Subglacial lakes in Antarctica host diverse microbes without sunlight.

- Deep subsurface environments rely on geochemical reactions.

- Ocean worlds maintain stability through global circulation.

- High-pressure atmospheres prevent volatile loss on locked planets.

- Stellar type influences heat redistribution efficiency.

Key Takeaways

- New models extend habitable zones inward for tidally locked planets around M and K dwarfs.

- JWST finds water on worlds closer to stars than traditional limits allow.

- Earth’s extremophiles suggest life persists under ice or in dark zones.

This shift promises to uncover more potential biospheres among the thousands of known exoplanets. As telescopes peer deeper into the cosmos, the definition of “habitable” evolves – what overlooked worlds might hold the key to life’s universality? Share your thoughts in the comments.