Imagine reaching the end of your life… and then quietly rewinding the clock, slipping back into your younger self, and starting again. No fantasy potion, no sci-fi machine – just biology. A few real animals on our planet pull off something that feels uncomfortably close to this, bending the rules of aging in ways that still shock scientists in 2026.

These creatures are not “immortal” in the magical sense. They can still be eaten, infected, or crushed under a rock. But inside their cells, something very unusual is happening. Instead of wearing down with time like a used battery, their bodies repair, reset, or simply… fail to age. Let’s dive into the strangest corners of nature and see how a handful of animals dodge the usual fate that the rest of us can’t escape.

The Jellyfish That Turns Back Time: Turritopsis dohrnii

Picture an old jellyfish drifting in the ocean, damaged or starving, and instead of dying, it morphs back into its baby form. That’s exactly what the tiny jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii can do, earning it the nickname “the immortal jellyfish.” When stressed by injury or harsh conditions, it transforms its adult body back into a polyp, the earlier stage of its life cycle, and effectively starts over.

This time-reversal trick is driven by a process called cellular transdifferentiation, where one type of cell turns into another type entirely, like a skin cell becoming a nerve cell. It is as if a retired person could become a teenager again with a completely rebuilt body. Scientists are intensely interested in this ability because it suggests that, under the right conditions, mature cells do not have to stay locked into one identity. While humans can’t do this, studying Turritopsis might one day offer clues to how we could repair damaged tissues far more deeply than we do now.

The Ageless Mole Rat: Why Naked Mole Rats Seem to Cheat Death

The naked mole rat looks like something between a wrinkled sausage and a badly rendered video game character, but its biology is wildly impressive. Unlike most mammals, its risk of dying does not seem to rise dramatically with age; older naked mole rats remain active, fertile, and relatively healthy. Some individuals have lived more than three decades, which is astonishing for an animal about the size of a mouse.

Researchers have found several reasons for this unusual resilience. Naked mole rats appear highly resistant to cancer, partly thanks to extra-strong cell-to-cell glue and protective molecules that help prevent tumors from forming. Their bodies also tolerate low oxygen and metabolic stress, reducing the wear-and-tear that usually accumulates over a lifetime. When I first read about them, I remember thinking they were like little biological tanks – ugly, yes, but quietly rewriting the rules of mammalian aging behind the scenes.

The Hydra: A Tiny Creature That May Not Age at All

Hydra are small, freshwater animals that look like little tubes with tentacles, and they might be one of the closest things we have to true biological immortality. Experiments following Hydra for years have found no obvious signs of aging – no rising death rate, no clear decline in reproduction, nothing that screams “old age.” If their environment stays kind and they avoid predators or accidents, they might just keep going.

The secret lies in their stem cells, which divide and renew almost constantly, replacing old cells with fresh ones at a steady rate. It is a bit like having a house that is always under perfect, seamless renovation – rotting boards swapped out before you ever see the damage. Hydra seem to maintain a balance between cell growth and cell death so well that they never reach that frail, degraded stage. For scientists, they are a living test case for what happens when the body’s repair systems stay “on” indefinitely.

The Long-Lived Ocean Giants: Greenland Sharks and Rockfish

Not all “almost immortal” animals are tiny or soft-bodied. Some are slow, massive, and ancient, quietly gliding through dark, cold water. Greenland sharks are one of the most dramatic examples: studies of their eye tissue suggest they can live for centuries, with some estimates putting the oldest individuals at well over two hundred years. They grow slowly, mature late, and drift through the deep North Atlantic like living time capsules.

Similarly, some species of rockfish in the Pacific Ocean can live for more than two centuries. What these animals share is a combination of slow metabolism, stable cold environments, and robust systems for repairing cellular damage. Their cells accumulate genetic errors far more slowly than ours do, and their bodies do not burn through energy as aggressively. In a way, they are playing life on “slow mode,” trading speed and flashiness for extreme longevity.

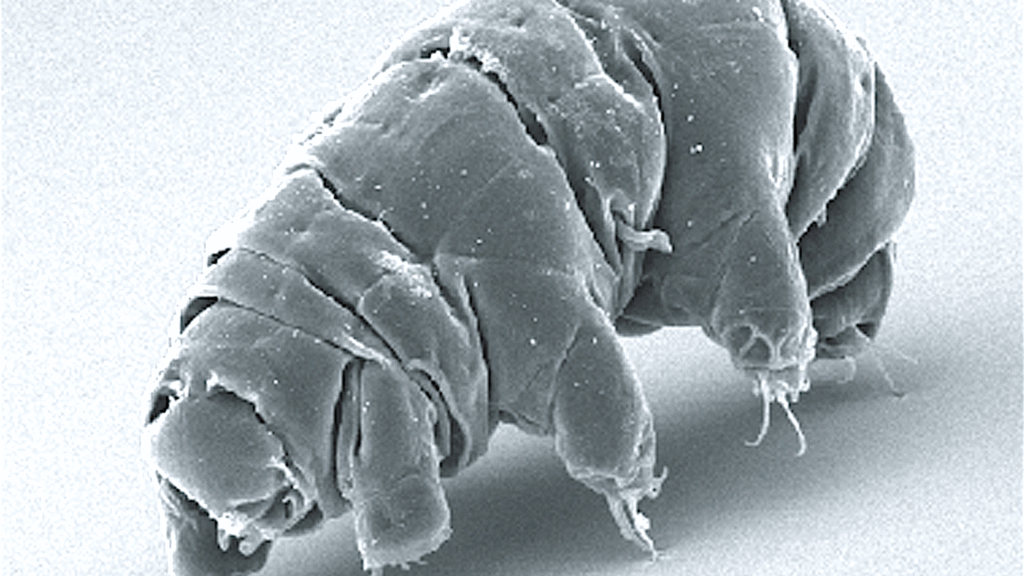

The Eternal Shell-Bearers: Tardigrades and Extreme Survival

Tardigrades, sometimes called water bears, are not immortal in the traditional sense, but their survival skills almost make death look optional. Under brutal conditions – drought, freezing, radiation – they curl into a dormant state called a tun, essentially hitting a pause button on life. In this state, their metabolism drops to nearly nothing and they can survive for years until conditions improve.

They have special proteins and sugars that protect their DNA and cellular structures from damage, acting like microscopic bubble wrap against the outside world. Tardigrades have survived exposure to space, intense radiation, and extreme temperatures that would kill almost any other animal. While they still age and die eventually, their ability to press pause on life adds another twist to what “endless” survival can look like in nature. It is less about never aging and more about being almost impossible to kill.

The Cellular Secrets: Telomeres, Repair Systems, and Low Damage

When you zoom in on all these so‑called immortal or ageless creatures, a pattern starts to appear. Many of them are unusually good at maintaining their DNA and preventing damage from piling up. They often have more active repair enzymes, more stable cell membranes, and powerful antioxidant systems that keep reactive molecules from wrecking their tissues. It is like having a built-in, around-the-clock maintenance crew that never clocks out.

Another key player is telomeres, the protective caps on the ends of chromosomes that normally get shorter with each cell division. In many long-lived or non-aging species, telomerase – the enzyme that rebuilds telomeres – stays more active, preventing this gradual erosion. Between better repair, slower metabolism, and these telomere tricks, their cells avoid the usual slide into dysfunction. Instead of racing toward decline, they stroll slowly, or barely move at all, on the aging timeline.

What Immortal Animals Teach Us About Our Own Future

So what does any of this mean for humans, who obviously cannot turn into jellyfish polyps or hydra tubes? For one thing, it proves that extreme longevity and even negligible aging are biologically possible. Nature has already solved many of the problems that cause our cells to break down: cancer resistance, stable stem cells, efficient repair systems. We are not guessing in the dark anymore; we have real models to study.

Researchers are exploring ways to borrow some of these tricks, whether by enhancing human DNA repair, protecting telomeres, or learning from animals that avoid cancer for most of their lives. It will not make us immortal in the sci‑fi sense, and there are huge ethical and practical questions about radically extending human lifespan. Still, every naked mole rat colony, every ancient shark, every tiny hydra quietly existing in a lab dish is a reminder that aging is not a fixed rule of the universe. It is a system – and systems, at least in theory, can be changed.