In a few billion years, the warm, familiar Sun we see every day will be unrecognizable. It won’t explode in a dramatic supernova, and it won’t quietly flicker out like a dying candle. Instead, it will shrink into something small, incredibly dense, and strangely beautiful: a white dwarf. That future is written into the Sun’s very nature, as surely as your adulthood is encoded in your childhood.

When I first learned this, it was oddly emotional. The Sun feels like the one constant in our lives, the backdrop to every morning commute, every childhood memory at the beach, every late afternoon walk. Realizing that even the Sun has an end point makes everything feel more fragile and more precious. But it also reveals a deeper story: our star is just one chapter in a grand cosmic pattern, and understanding that pattern helps us understand our own place in the universe.

What Kind of Star Is the Sun, Really?

Here’s the surprising part: for all the myths and poetry surrounding it, the Sun is actually a very average star. Astronomers classify it as a G-type main-sequence star, which sounds dull, but that “main-sequence” label is important. It means the Sun is in the long, stable phase of its life where it shines by steadily fusing hydrogen into helium in its core. Think of this as stellar adulthood: past the chaotic growing pains, not yet facing old age.

The Sun is a bit bigger and brighter than many stars in our galaxy, but it’s nowhere near massive enough to become a supernova. That limitation is what seals its fate as a future white dwarf instead of something more explosive. There’s a kind of comfort in that ordinariness. Our star isn’t a cosmic diva; it’s part of the vast majority of stars that follow a quieter, slower path through life and death.

How Nuclear Fusion Keeps the Sun Alive

Right now, the Sun is powered by an astonishing engine at its core: nuclear fusion. Under crushing pressure and blistering temperatures, hydrogen nuclei are slammed together so hard they fuse into helium, releasing energy that eventually escapes as sunlight. Every second, the Sun turns an enormous amount of hydrogen into energy, yet it barely notices the loss because it started with such a huge supply. It’s like burning a teaspoon of fuel out of a mountain-sized tank.

This fusion energy pushes outward, while gravity tries to pull everything inward. The result is a delicate balance that keeps the Sun stable in size and brightness. As long as there’s plenty of hydrogen in the core, this tug-of-war remains mostly even. That’s why the Sun has been shining steadily for about four and a half billion years and will continue to do so for billions more. The calm we see in the sky is really the product of an intense, invisible struggle deep inside.

The Future Red Giant: When the Sun Swells and Boils Worlds

The real drama begins when the hydrogen in the Sun’s core runs low. Once it can’t fuse enough hydrogen in its core to counter gravity, the core starts to contract and heat up while the outer layers expand. The Sun will swell into a red giant, growing so large that it’s expected to engulf Mercury and Venus and possibly scorch or swallow Earth. The gentle yellow disk we know today will turn into a bloated, reddish star dominating the sky from horizon to horizon.

As the Sun expands, its outer layers will cool and redden, but its core will become hotter and more compressed. That compact core will eventually begin fusing helium into heavier elements like carbon and oxygen. For a while, the Sun will flicker between relative stability and intense changes, shedding mass and blowing off gas in powerful stellar winds. If you tried to imagine a slow-motion apocalypse, this red giant phase would be a pretty accurate picture for the inner solar system.

Planetary Nebula: The Sun’s Beautiful Final Performance

In its late stages as a red giant, the Sun won’t quietly fade away; it will peel off its outer layers into space. Those layers of gas will drift outward and get lit up by the hot, exposed core in the center. From a distance, this will form what astronomers call a planetary nebula: a glowing shell of gas with intricate shapes and colors. Despite the name, it has nothing to do with planets; it just looked vaguely planet-like through early telescopes.

These planetary nebulae can be surprisingly delicate and complex, like cosmic soap bubbles or ghostly flowers. They are short-lived on cosmic timescales, lasting only tens of thousands of years before fading into the surrounding space. But in that brief window, they mark a star’s graceful exit from its active life. Our Sun, one day, will leave behind its own luminous cloud, quietly advertising its past existence long after the inner planets have been baked and battered beyond recognition.

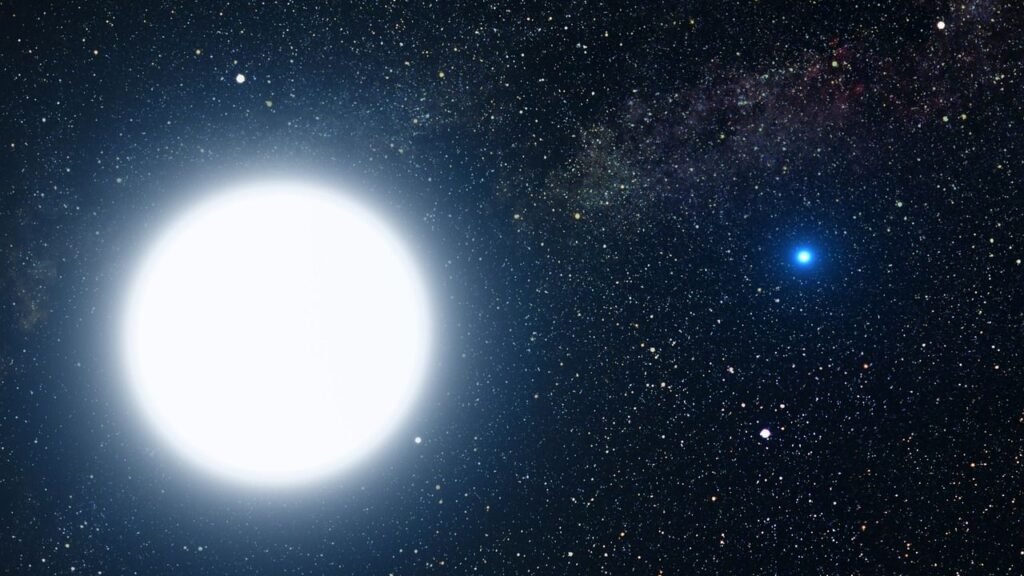

The White Dwarf: A Sun Crushed to the Size of Earth

At the center of the planetary nebula will sit what’s left of the Sun: a white dwarf. This object will have about half the Sun’s original mass squeezed into a volume roughly similar to Earth’s size. The density is almost impossible to imagine. A teaspoon of white dwarf material would weigh as much as a mountain. The Sun’s matter will have collapsed into a form where gravity is balanced not by fusion, but by the quantum behavior of electrons packed tightly together.

White dwarfs don’t generate new energy by fusion. They shine because they are still incredibly hot, slowly radiating away the heat they built up over billions of years. Over even longer timescales, they cool and dim, turning from a bright white ember into a faint, fading cinder. It’s a strange image: our huge, life-giving Sun ultimately reduced to a burnt-out core, no larger than the planet we walk on. And yet that quiet remnant is just as much a part of its story as the brilliant star we see today.

Why the Sun Won’t Explode in a Supernova

There’s a common misconception that all stars eventually explode as supernovae, but that’s not true. Only stars that are significantly more massive than the Sun end their lives in those titanic blasts. The Sun doesn’t have the mass required to compress its core to the point where more extreme reactions kick in. Instead, once it has exhausted the fuel it can reasonably burn, it settles for the gentler path of shedding its outer layers and contracting into a white dwarf.

In a way, the Sun’s lack of dramatic mass is our saving grace. If it were much larger, its life would have been shorter and far more violent, and Earth might never have had the calm, stable conditions needed for life to develop. The “boring” fate of becoming a white dwarf is exactly what made Earth’s long, quiet habitability possible. That unremarkable ending is the flip side of the long, steady story that gave us oceans, forests, cities, and every memory you’ve ever had under daylight.

What the Sun’s Fate Tells Us About Our Own

Knowing the Sun’s future isn’t just a piece of trivia; it changes how the solar system feels in your mind. Every sunrise becomes part of a larger timeline, a brief calm interval in a star’s life that won’t last forever. Earth’s habitability is a temporary window, not a permanent guarantee. Long before the Sun reaches its white dwarf phase, the red giant stage will make our world unlivable, no matter how advanced any future civilization might be.

At the same time, there’s something oddly reassuring about the predictability of it all. The Sun is not planning any sudden surprises; its evolution is governed by physics we understand well. Its future as a white dwarf is written not in prophecy, but in mass, temperature, and the laws of nature we test every day. If even our star is mortal, then change and impermanence aren’t failures in the universe’s design – they’re the rule. Knowing that, what does it make you want to do with the time while the Sun is still in its brightest, most generous years?