The deepest place on Earth is not a quiet, lifeless graveyard at the bottom of the Pacific; it is a restless frontier, where crushing pressure, perpetual night, and alien life collide in ways we are only beginning to understand. The Mariana Trench has become a kind of scientific mirror, reflecting how far technology can push and how much we still do not know about our own planet. In just the last decade, a handful of daring descents and new robotic surveys have transformed it from a cartographic label on a map into a dynamic, data-rich research site. Yet for all the headlines about record-breaking dives, most of the trench remains unexplored, and every new measurement seems to complicate the story rather than simplify it. This article dives into that tension between myth and measurement, between untouched wilderness and human footprint, and asks what it really means to explore the deepest point on Earth.

A Canyon Bigger Than Our Imagination, Carved Into the Pacific

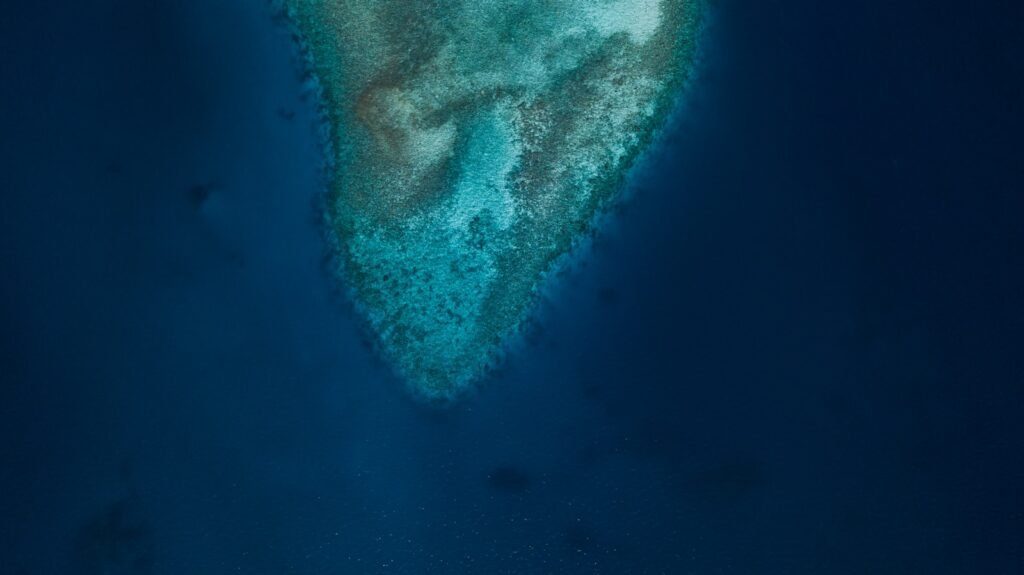

The Mariana Trench arcs like a scar in the western Pacific Ocean, east of the Mariana Islands, stretching for roughly about one thousand five hundred miles in length and plunging to depths of around seven miles at its deepest known point. It is not a neat, singular hole but a complex subduction zone, where the Pacific Plate is thrust beneath the smaller Mariana Plate and dragged downward into the mantle. That slow, relentless tectonic collision has created a landscape of steep slopes, narrow valleys, and fault-slashed walls that would dwarf even the grandest terrestrial canyons. Even after decades of mapping, large sections of its flanks are still represented by relatively coarse bathymetric data compared with shallow coastal seas.

For context, if you dropped Mount Everest into the Challenger Deep, its summit would still lie under more than a mile of water. At the trench floor, pressures exceed one thousand times the atmospheric pressure at sea level, a physical reality that turns air-filled spaces into crushed metal and shattered glass in an instant. Light from the surface is completely gone, replaced by a darkness so complete that even seasoned explorers describe it less as a visual experience and more as an atmosphere you feel. The trench sits at the extreme end of a continuum of deep ocean environments, yet it is still very much connected to global processes of plate motion, climate, and biogeochemical cycles.

Challenger Deep: A Contested “Deepest Point” on a Moving Planet

Challenger Deep, the most famous depression within the Mariana Trench, has long been the shorthand answer to the question of where Earth is deepest, but that simplicity is increasingly misleading. Different expeditions using different sonar technologies and calibration standards have produced slightly different maximum depth values, varying by tens of meters. That might sound minor, but at this level of precision, those discrepancies spark real scientific debates about instrumentation, methodology, and how we define a single “deepest point” in a rugged seafloor landscape. There are also multiple small basins within Challenger Deep itself, sometimes called the western, central, and eastern pools, each with slightly different measured depths.

To complicate things further, the seafloor is not frozen in time. Tectonic activity, sediment slumping, and even large earthquakes can subtly reshape the trench, changing depths by amounts that matter once you are arguing over the last handful of meters. Modern multibeam sonar surveys and repeated measurements are steadily narrowing the uncertainty, but there is no courtroom-style moment where a judge bangs a gavel and declares a final number for all time. Instead, Challenger Deep is better understood as a living geophysical feature whose deepest exact coordinate and depth are snapshots of an evolving system rather than eternal truths chiseled into stone.

Life Under a Thousand Atmospheres: Creatures Built for the Impossible

One of the most stubborn myths about the deep ocean was that extreme pressure would make life impossible, and the Mariana Trench has helped demolish that idea. Explorers have filmed translucent snailfish gliding close to the seafloor in the hadal zone, their bodies adapted with flexible bones, specialized cell membranes, and pressure-stabilizing molecules that keep proteins from collapsing. Amphipods the size of a human hand scavenge for organic scraps, coated in gelatinous layers that may help them withstand the crushing environment. Microbial communities, thriving in sediments and on rocks, harness chemical gradients rather than sunlight, turning the trench floor into a patchwork of invisible biochemical factories.

What is striking is not only that organisms survive, but that they seem to exploit niches that simply do not exist higher in the water column. The absence of large predators we are familiar with from shallower waters, such as sharks, shifts the balance of who eats whom and how energy moves through the system. Researchers have also found that many trench species are highly specialized, with narrow depth ranges, meaning they may be uniquely vulnerable to any environmental changes at those exact pressures and temperatures. Instead of being an evolutionary dead end, the hadal realm of the Mariana Trench now looks more like a separate branch of the tree of life, pruned and shaped by physics most of us will never experience directly.

Human Footprints at the Bottom of the World

For a place that feels so remote, the trench is already marked by human activity in ways that are hard to ignore. During dives and lander deployments, researchers have seen plastic debris such as bags, food wrappers, and fragments of synthetic materials resting quietly on the seafloor. Chemical analyses of amphipods collected from the trench have revealed persistent industrial pollutants, including certain legacy flame retardants, at concentrations that surprised even seasoned scientists. Microplastics have been detected in trench organisms, showing that our waste follows currents and sinks, infiltrating even this extreme environment.

This contamination is more than an aesthetic shame; it raises real questions about how pollutants move through the deepest food webs and how long they may remain there. The hadal zone does not flush quickly like a river; it is more like a deep archive where particles, plastics, and chemicals accumulate over long time scales. That means the Mariana Trench has become both a symbol of planetary wilderness and a stark indicator of how thoroughly human activity reaches into every corner of the biosphere. For all the talk of “untouched depths,” the evidence suggests that we have already left fingerprints on the very bottom of the ocean.

Engineering the Descent: How We Learned to Touch the Seafloor

Reaching the bottom of the Mariana Trench has always been as much an engineering drama as a scientific quest. The first crewed descent in the early 1960s used a bathyscaphe with a gasoline-filled float and a tiny steel sphere built to survive unimaginable pressure, an approach that now looks almost improvised compared with modern submersibles. Later expeditions, including commercially built deep-diving craft, have relied on advanced syntactic foam for buoyancy, high-strength metal alloys, and intricate life-support systems miniaturized to fit inside pressure-resistant hulls. Each successful descent is preceded by years of design, simulations, and incremental tests at lesser depths to verify that a single weak seal or cable will not fail catastrophically in the hadal zone.

Uncrewed landers and remotely operated systems add another layer of innovation, allowing researchers to drop instrument packages to the trench floor, communicate acoustically, and retrieve them hours later. These platforms can carry high-resolution cameras, sediment samplers, chemical sensors, and even experimental chambers to test how organisms respond to changing conditions. The technological arc of trench exploration, from early analog gauges to digital sensor networks, mirrors a broader trend in oceanography: using sophisticated, often custom-built systems to wrestle with environments that would quickly kill unprotected humans. Every trip to the Mariana Trench therefore doubles as a test bed for materials science, robotics, and deep-sea engineering that can be adapted elsewhere.

What the Trench Teaches Us About Earth’s Hidden Engines

Beyond the fascination with depth records and strange animals, the Mariana Trench is a laboratory for understanding how our planet works at a fundamental level. The subduction happening here is part of the giant conveyor belt that recycles oceanic crust into the mantle, influences volcanic arcs, and shapes the chemistry of the oceans and atmosphere over geological time. Fluids squeezed from the descending plate transport elements like carbon, sulfur, and trace metals, feeding reactions that can generate unique mineral deposits and fuel microbial ecosystems. By sampling rocks, sediments, and pore waters in and around the trench, scientists get rare, direct evidence of processes that are otherwise mostly inferred from distant seismic data and models.

In a sense, studying the Mariana Trench is like prying open a seam in Earth’s surface and peering into the machinery below. The extreme pressure and low temperature at depth also make it an analog environment for other worlds, such as the hidden oceans believed to exist beneath the icy crusts of Europa or Enceladus. Insights into how life and geology interact under these constraints help refine our expectations for where life might exist beyond Earth and what kinds of biosignatures to look for. The trench, then, is not an isolated curiosity but a node in a much larger network of questions about planetary evolution and habitability.

Rethinking “Unexplored”: How New Data Are Rewriting Old Assumptions

For years, it was common to say that we knew more about the surface of the Moon than the deep ocean, and the Mariana Trench was often trotted out as Exhibit A. That comparison is now less accurate as multibeam sonar, autonomous vehicles, and long-duration landers have filled in blank spaces on the map and produced continuous records of environmental conditions. These technologies reveal that the trench is not a static abyss but a place of intermittent disturbance: landslides reshaping walls, turbidity currents sweeping down from the slopes, and subtle seismic shifts altering stress patterns along faults. What once looked like a still, eternal void is now recognized as a dynamic system where change is the rule rather than the exception.

At the same time, the new data have exposed how fragmented our understanding remains. Most of the high-resolution work has focused on specific sites of interest, such as Challenger Deep, leaving vast stretches of the trench relatively under-sampled. There is also a bias toward physical measurements and striking imagery, while long-term ecological monitoring lags behind because it is harder, slower, and more expensive. The net result is that every new survey tends to overturn some earlier simplification, pushing us away from tidy narratives of “mysterious depths” and toward a messier, more nuanced picture of gradients, variability, and exceptions to the rule.

Unfinished Questions in the Planet’s Deepest Laboratory

Even with all the recent attention, the Mariana Trench remains riddled with open questions that cut across disciplines. Biologists still do not know how many species are truly endemic to the hadal zone here, or how populations in the Mariana connect, if at all, to those in other deep trenches. Geophysicists are working to refine models of how water and volatile elements are transported into the mantle at subduction zones, and how that movement affects earthquakes and volcanism over time. Chemists are probing how long pollutants like microplastics and industrial chemicals persist in trench sediments, and whether they transform as they sink and settle.

There is also an ethical dimension that has not been fully resolved: how intensely should we use this environment for science, technology testing, or even tourism, now that deep-diving vehicles are no longer purely government projects. Each additional visit, sensor deployment, or trial run carries the potential to add noise, disturbance, or contamination. The challenge is to balance the desire for knowledge and innovation with a precautionary mindset that recognizes the trench as both resilient and fragile. In that sense, the Mariana Trench serves as a test case for how humanity approaches the last remaining frontiers on Earth.

How You, on Dry Land, Can Help Protect the Deepest Places

It can feel abstract to worry about a place you will almost certainly never visit, but daily choices on land do echo all the way down to the trench floor. Reducing single-use plastics, supporting policies that strengthen wastewater treatment, and backing organizations that advocate for stronger protections of the high seas all help shrink the flow of debris and chemicals into the ocean system that ultimately feeds the hadal zones. Paying attention to how seafood is harvested and favoring sustainably certified options can also lessen pressures on deep-sea ecosystems connected to trench environments through broader food webs.

Just as important is staying curious and informed. Reading and sharing quality science reporting, following reputable oceanographic institutions, and encouraging schools to include deep ocean science in their curricula all create a culture that values what lies beyond the shoreline. The Mariana Trench may be unimaginably distant, but it is part of the same interconnected planet that shapes weather, climate, and resources in your everyday life. Remembering that the darkest, deepest places are not empty but vibrant, vulnerable systems is a small mental shift with big consequences for how we treat the world as a whole.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.