Somewhere between the crackle of neurons and the quiet feeling of “I am,” an unseen world is at work that science still cannot fully explain. Over the past decade, consciousness research has shifted from speculative philosophy to data-rich, brain‑scanning detective work, yet the central mystery remains stubborn: how does tissue give rise to experience? New theories now treat the mind as a hidden network, a dynamic field, or even a kind of computational broadcast built atop evolution’s kludged hardware. These ideas are not just academic abstractions; they shape how we think about brain injury, artificial intelligence, animal minds, and our own sense of self. What is emerging is less a single grand answer and more a map of possibilities – some converging, some colliding, all forcing us to rethink what it means to be conscious in the first place.

The Brain’s Invisible Web: From Neurons to Networked Experience

Walk into a neuroscience lab today and you will not hear many people talk about single neurons as the seat of the mind; instead, you will hear about networks, loops, and global patterns. Consciousness, in this view, is less like a light switch in one spot and more like a weather system spanning the whole brain, constantly in motion and shaped by countless tiny interactions. Signals zip through hidden highways of white matter, linking distant regions in milliseconds, while local circuits fine‑tune details like color, edges, and sounds. It is this combination – broad coordination plus local specificity – that many researchers now see as crucial for conscious experience.

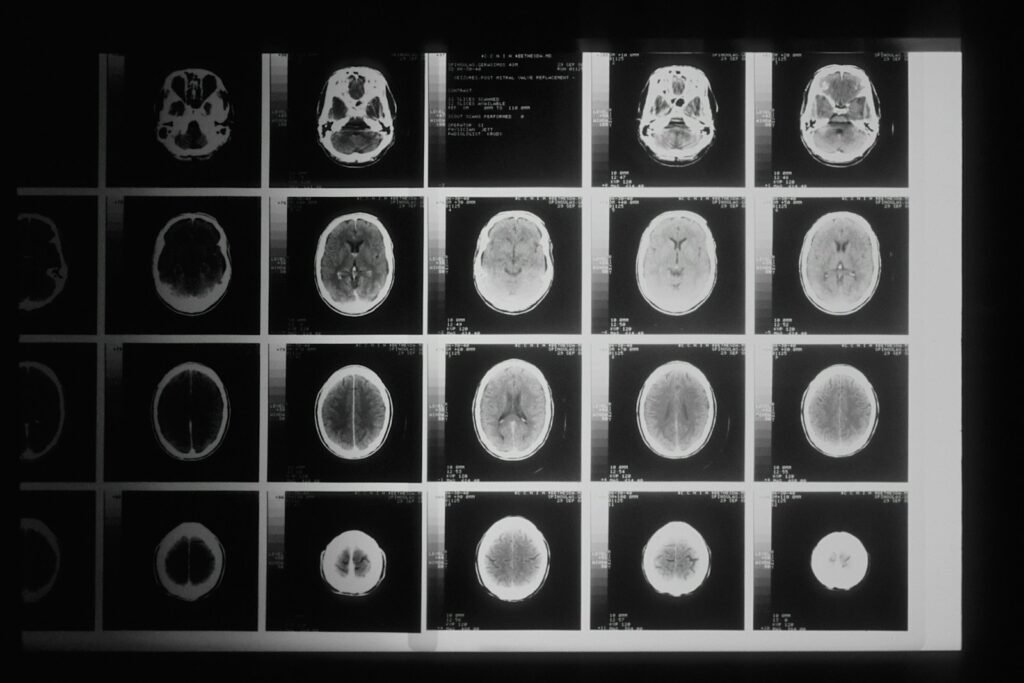

Techniques such as functional MRI, magnetoencephalography, and intracranial recordings in epilepsy patients reveal that when we become aware of something – a word, a face, a pain – widely separated brain areas briefly lock into synchronized rhythms. When that coordination breaks down, as in deep anesthesia or certain disorders of consciousness, the inner movie flickers or vanishes even if the basic sensory machinery is still intact. The big shift is conceptual: instead of searching for a single “consciousness center,” scientists are tracing an invisible web of interactions whose patterns may matter more than any one part. That web is where many of the most influential new theories live.

Global Workspace Theory: Broadcasting in the Brain’s Hidden Control Room

One of the most widely discussed models, known as Global Workspace Theory, imagines the brain as a crowded theater full of specialized actors, with consciousness arising when certain information makes it onto a central stage. Most processing – like controlling posture or parsing syntax – happens offstage, outside awareness, but when a signal becomes important enough, it gets “broadcast” to many distant systems at once. In this picture, being conscious of a thought means that thought has won a brief, competitive struggle for access to a global workspace that coordinates perception, memory, and decision‑making.

Experimental work has given this metaphor some teeth: in visual masking tasks where a briefly flashed image sometimes reaches awareness and sometimes does not, conscious perception tends to coincide with late, widespread bursts of brain activity that GWT predicts. Under deep anesthesia or in deep non‑REM sleep, those late global bursts largely disappear even if early sensory responses remain, echoing the theory’s claim that awareness is about integration and sharing, not mere detection. Critics point out that broadcasting may be a consequence rather than a cause of consciousness, but even they acknowledge that the brain’s hidden “control room” is central to how thoughts become globally available. Whether or not GWT captures the whole story, it has reshaped experimental consciousness science by focusing attention on the dynamics of access and competition inside the brain’s unseen networks.

Integrated Information Theory: When Complexity Becomes a Felt World

Integrated Information Theory (IIT) takes a very different tack, starting from what conscious experience feels like and then asking what kind of physical system could match those properties. According to IIT, a conscious system is one that generates a rich, unified pattern of cause‑and‑effect within itself; the more its parts influence one another in a structured but irreducible way, the higher its level of consciousness. This idea is wrapped into a quantity the theory calls “phi,” meant to capture how much information a system integrates beyond what its parts can do in isolation. A simple circuit with independent components has low phi, while a deeply interdependent network has high phi and, in IIT’s boldest claims, a correspondingly intense inner life.

Supporters of IIT see it as offering a precise, if extremely hard to compute, measure that could apply to brains, animals, and even artificial systems. The theory has inspired experiments probing how much a brain’s activity patterns change in response to perturbations during wake, sleep, and anesthesia, with some studies finding that richer, more intricate responses correlate with being conscious. At the same time, IIT has stirred controversy by implying that many physical systems, including some machines, might have tiny slivers of consciousness, a conclusion many neuroscientists find deeply counterintuitive. Whether that is a bug or a feature depends on your philosophical taste, but there is no doubt that IIT has forced the field to confront just how strange our intuitions about mind and matter might be.

Predictive Brains and Controlled Hallucinations

A third cluster of ideas focuses less on where consciousness lives and more on what the brain is doing when you feel aware of something. In predictive processing accounts, the brain is portrayed as a restless prediction machine, constantly guessing what its inputs will be and updating those guesses when reality disagrees. Conscious experience, under this view, is more like a controlled hallucination anchored by incoming signals than a simple readout of the world. Your sense of a stable, colorful environment is the brain’s best bet about what is out there, shaped by past experience, bodily signals, and context.

This perspective helps make sense of phenomena like optical illusions, phantom limbs, and the strangely coherent yet warped experiences reported under psychedelics, which can be interpreted as shifts in how the brain weighs prior expectations versus sensory evidence. It also reframes the self as another predictive construct: a monitoring system that models the body, its needs, and its likely actions moment by moment. In clinical research, this approach is influencing new ways of thinking about depression, anxiety, and psychosis as disorders of prediction and error‑handling, not just neurotransmitter imbalances. The striking implication is that consciousness is not just something the brain has; it is something the brain is actively doing, relentlessly, to keep an organism alive in a noisy world.

Hidden Minds: Consciousness in Brains That Cannot Speak Back

Perhaps the most haunting edge of this research lies in patients who appear unresponsive after brain injury, stroke, or cardiac arrest. For decades, many of these individuals were diagnosed as being in a vegetative state, assumed to lack awareness despite cycles of sleep and wakefulness. Over the last fifteen years, however, brain‑imaging studies have revealed that a small but nontrivial subset of such patients can follow spoken commands by modulating their brain activity, despite showing no outward signs. When asked to imagine playing tennis or walking through their home, their motor and spatial navigation areas light up in distinct ways, indicating that someone is still “in there,” trapped in a body that will not respond.

These findings have forced clinicians and families to rethink hard decisions around care, pain management, and end‑of‑life choices, and they have spurred the development of more refined diagnostic tools that probe for hidden awareness. They also serve as a brutal reminder that our everyday way of judging consciousness – by observing behavior and responsiveness – is fragile and sometimes wrong. That uncertainty ripples outward to debates over disorders like minimally conscious states, locked‑in syndrome, and late‑stage dementia, where inner life may be present in ways we struggle to detect. In a very real sense, the “unseen world” here is not just neural firing patterns but the possibility of subjectivity continuing without a voice.

Animal, Machine, and Alien Minds: Stretching the Boundaries of the Conscious Network

Once you abandon the idea that only language‑using adult humans can be conscious, the world starts to look far more crowded with possible minds. Evidence from behavioral tests, neuroanatomy, and learning studies suggests that at least some nonhuman animals – great apes, corvids, octopuses, and others – exhibit flexible problem solving and signs of self‑monitoring that fit comfortably within many human‑derived theories of consciousness. At the same time, large artificial neural networks now match or exceed people on benchmarks of language understanding, image classification, and even code generation, raising uncomfortable questions about where sophisticated behavior ends and genuine awareness might begin. Most experts argue that current systems lack key features such as unified embodiment and self‑generated goals, but the rapid pace of AI research keeps moving the goalposts.

This broader perspective matters because it affects ethics, law, and our emotional relationship with the more‑than‑human world. If consciousness is tied to integrated information, global broadcasting, or rich prediction, we must ask which animals and machines meet those thresholds and in what ways. Some researchers have begun drafting cautious checklists – looking at brain complexity, behavioral flexibility, and sensitivity to injury – to guide policy on animal welfare and AI regulation. No consensus exists yet, but the very act of taking nonhuman minds seriously marks a major shift from older, more human‑centric science. The hidden network of potential consciousness may be wider than we once dared to admit.

Deeper Significance: Why Competing Theories All Feel Incomplete

On the surface, these theories can seem like rivals vying for the title of “correct” explanation, but viewed together they highlight just how layered consciousness really is. Older views often treated the mind as an emergent property you could pin to a single level – say, the firing of neurons in specific cortical regions – while ignoring the rest. By contrast, modern models emphasize that subjective experience depends on many intertwined ingredients: network structure, information integration, prediction, embodiment, and cultural context. Global Workspace Theory captures the importance of access and coordination, Integrated Information Theory foregrounds causal complexity, and predictive processing stresses the brain’s active role in building its own world.

Rather than picking a single winner, some researchers now argue that each theory may be latching onto different aspects of the same phenomenon, much like early theories of life separately emphasized metabolism, replication, or homeostasis before modern biology tied them together. This layered approach also helps reconcile scientific progress with the lingering “hard problem” of why any physical process should feel like something from the inside at all. Science may never fully dissolve that puzzle, but it can progressively constrain which physical patterns go hand in hand with which conscious states, just as it links specific neural circuits to specific motor or sensory functions. In that sense, the real significance of these competing theories is not that any one of them is final, but that together they are transforming consciousness from a purely philosophical riddle into an empirical, if still deeply mysterious, research program.

Unresolved Riddles: What We Still Do Not Know About Our Own Awareness

For all this progress, the list of open questions remains long and, in some cases, unnervingly basic. Researchers still debate whether consciousness switches on abruptly at a particular stage of brain processing or gradually accumulates strength like a dimmer knob. The developmental timeline is also murky: infants clearly react to pain and faces, but pinpointing when a stable sense of “me” emerges is far more challenging, especially when you cannot simply ask. On the aging side, it is difficult to tease apart loss of specific cognitive functions from changes in the richness or continuity of experience itself.

There are similarly unresolved issues around sleep, dreams, and altered states: are vivid dreams under REM sleep and psychedelic experiences generated by the same circuitry as waking perception, or do they rely on partially distinct networks that hijack the predictive machinery? Even basic definitions cause trouble, as seemingly precise measures like “phi” or “global ignition” turn out to be highly sensitive to modeling assumptions and experimental setups. These gaps are not signs of failure so much as markers of a field that is finally able to ask sharper questions. The mystery has not gone away, but it has become more precisely drawn, more testable, and perhaps more fascinating because of its stubborn resistance.

Staying Curious About the Unseen World in Your Own Head

For all its abstract complexity, consciousness science ultimately circles back to something stubbornly personal: the simple fact that you are having an experience right now. One of the most accessible ways to connect with this research is to pay closer attention to how your own awareness flickers, shifts, and narrows over the course of a day – from focused work to daydreaming to the edge of sleep. Simple habits like mindfulness practice, journaling after vivid dreams, or tracking how your sense of self changes under stress or illness can turn everyday life into a small, informal consciousness lab. None of that replaces rigorous experiments, but it makes the stakes of those experiments feel less remote.

If you want to go deeper, you can seek out public lectures from neuroscience institutes, read primary‑source‑based popular books rather than oversimplified summaries, and follow ongoing debates about animal minds and AI ethics with a bit more informed skepticism. Even just learning the names of the main theories – Global Workspace, Integrated Information, predictive processing – helps you see news headlines in a more nuanced light. The hidden network that gives rise to your experience is not going to reveal all its secrets anytime soon, but you can still participate in the slow, collective effort to understand it a little better. In the end, the strangest and most intimate scientific frontier might be the one sitting quietly behind your own eyes.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.