For centuries, Neanderthals have been cast as brutish Ice Age relatives of Homo sapiens, but the discoveries of 2025 continue to overturn old stereotypes while revealing surprising new facets of their lives. From evidence of advanced behaviors and survival strategies to biological differences that may have influenced their fate, this year’s research is painting a richer, more complex portrait of our closest extinct relatives.

Scientists are now uncovering clues that Neanderthals may have invented controlled fire, engaged in symbolic expression and developed unique metabolic and genetic traits — all while their populations fluctuated dramatically over time. These insights are transforming how researchers view Neanderthal culture, biology and their long-standing interactions with the environment and other hominins.

Fire-Making Pioneers of the Paleolithic

One of the most dramatic revelations of 2025 is evidence suggesting that Neanderthals were among the first hominins to deliberately make and control fire more than 400,000 years ago — far earlier than previously documented for human ancestors. Researchers discovered heat-shattered flint and pyrite flakes in England that indicate intentional fire production rather than opportunistic use of wildfires.

Controlled fire use would have allowed Neanderthals to cook food, stay warm in cold climates and forge tools, showing a degree of technological and cognitive sophistication that rivals early Homo sapiens and shatters the outdated image of Neanderthals as primitive.

Cannibalism and Social Stress

While Neanderthals were clearly capable innovators, 2025 studies also reinforce evidence of cannibalism that may have targeted women and children within some groups. At the Goyet cave in Belgium, researchers found remains with butchery marks similar to those on animal bones, underscoring that cannibalism — for reasons still debated — was part of some Neanderthal lifeways.

This grim behavior might reflect resource stress, group conflict or social ritual, and contrasts with evidence of cultural and technological achievements, highlighting the complexity and variability of Neanderthal social structures.

Traces of Art and Symbolism

Neanderthals also appear to have engaged in symbolic activity once thought exclusive to modern humans. In Spain, researchers uncovered a 43,000-year-old ocher fingerprint on a rock likely made by Neanderthals, suggesting early symbolic marking or art.

Additionally, discoveries in Crimea of ocher “crayons” sharpened repeatedly hint that these pigments may have been used for drawing or symbolic decoration — evidence of cultural expression and possibly communication that goes beyond utilitarian tool use.

Physiology and Genetic Insights

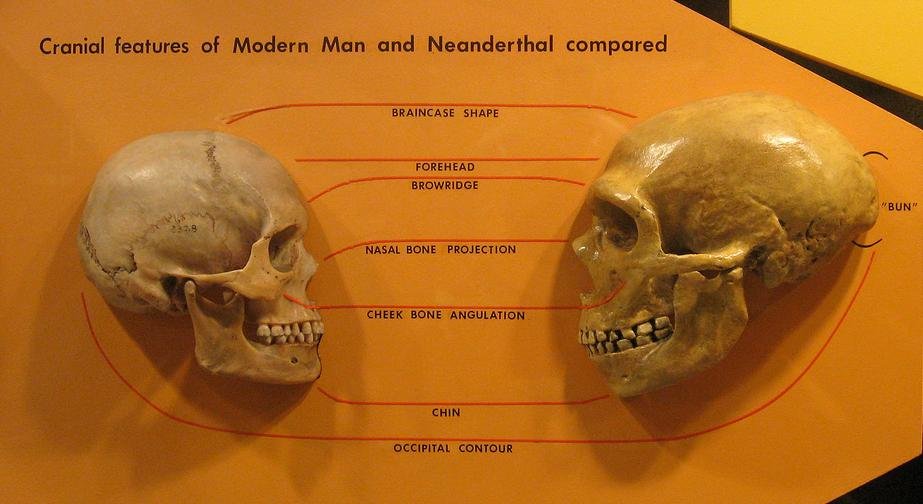

Biological research in 2025 also struck key notes: Neanderthals carried unique gene variants that influenced their physiology. One study found that a Neanderthal enzyme variant may have hampered high-intensity athletic performance, implying a different energy metabolism compared to modern humans.

Neanderthals were also found to be more susceptible to lead poisoning due to genetic differences, while modern humans evolved protective variants. These genetic disparities may have given Homo sapiens subtle survival advantages in changing environments — possibly influencing long-term competitive dynamics.

Nutritional Strategies and Population Stress

Research also revealed that Neanderthals practiced advanced nutritional strategies like operating what scientists call a “fat factory,” processing animal bones to extract calorie-rich marrow and fats — a technique to stave off protein poisoning during lean times.

Despite such adaptability, fossil evidence suggests Neanderthal populations underwent a severe bottleneck around 110,000 years ago, reducing their genetic diversity and possibly weakening their resilience to environmental shifts.

A Bumpy Demographic Path to Extinction

This year’s research also underscores that Neanderthal life was not static. Population fluctuations, genetic differences and ecological pressures all played a role in shaping their evolutionary trajectory. The combination of environmental stressors and biological constraints may have contributed as much to their eventual disappearance as competition with Homo sapiens.

These insights reveal that Neanderthals were neither simple brutes nor static cave dwellers but dynamic beings who innovated, adapted and expressed themselves in ways once thought uniquely human.

Rethinking Our Extinct Cousins

The discoveries of 2025 force a reevaluation of Neanderthals not as evolutionary side notes but as complex hominins with rich cultural lives, sophisticated survival tactics and genetic legacies that still echo in us today. The evidence that they made fire intentionally, used pigments symbolically and managed nutrient resources intelligently blurs the lines we once drew between them and modern humans.

Yet genetic and demographic vulnerabilities remind us that evolution is not just about brilliance but also about fragility in the face of change. As researchers continue to unearth new data, it becomes ever clearer that Neanderthals were not so different from us — and understanding their successes and failures could illuminate not only our past but the challenges our own species may face in a world of rapid environmental change.