Have you ever wondered whether awareness truly switches off when the brain goes quiet, or if some hidden part of us keeps watching from the shadows? Modern neuroscience has been poking at this question with scalp electrodes, MRI scanners, and some frankly wild experiments involving anesthesia, coma, and near‑death states. What they’re finding is uncomfortable and fascinating: the line between “conscious” and “unconscious” is far blurrier than most of us were taught.

I still remember reading about a patient under general anesthesia who seemed completely unresponsive, yet their brain lit up in patterns almost identical to a person who was awake and listening. That stuck with me. It made me rethink what it really means to be “there” or “gone.” As of 2025, we know much more than we did a decade ago, but awareness is still one of the strangest mysteries we live inside every day.

The Shocking Puzzle Of Silence: Does Awareness Really Turn Off?

When doctors say the brain has “gone silent,” they usually mean that large, synchronized waves of slow activity have taken over, or that measurable responses to the outside world have faded away. On an EEG, deeply unconscious states like coma or general anesthesia often look like a calm ocean instead of a storm of rapid, mixed activity. From the outside, the person seems totally gone: eyes closed, no reactions, body limp, no obvious sign that anything is happening inside. It’s tempting to treat that as proof that awareness has vanished.

But when people wake up from such states, they sometimes report vivid experiences that seemed to occur during the quietest moments of their brain activity. They remember conversations, sounds, or intense inner worlds, even when their brain signals looked almost flat or highly slowed down at the time. This mismatch between what we see in the brain and what people later describe is what makes the puzzle so unsettling. If the instruments say “no one home” while the person later insists “I was there,” it forces us to question whether silence on the monitor really means silence in the mind.

What Neuroscience Says About Consciousness Going Offline

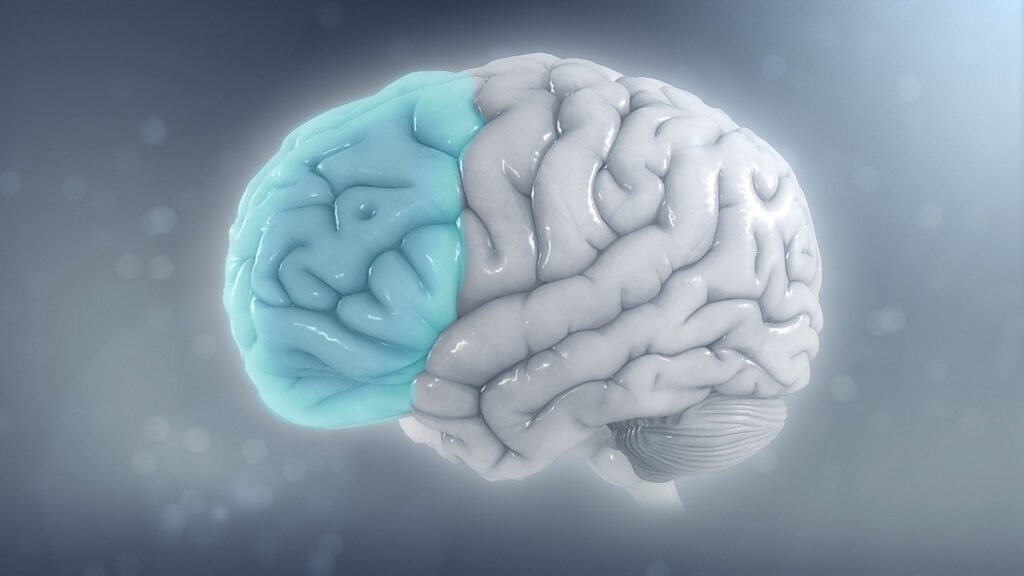

Neuroscientists today generally think of consciousness as something that depends on communication across many regions of the brain, not just one specific “light switch” area. A widely discussed idea is that awareness requires both rich information and widespread sharing of that information between distant networks, like different departments in a company constantly talking to each other. When anesthetics or deep sleep states kick in, they tend to block or scramble this long‑range communication, even if local regions of the brain keep humming along. So the brain is not literally dead or frozen; it’s more like a bunch of isolated islands with no phone lines between them.

Several research teams have tried to measure how “connected” a brain is in real time by looking at the complexity and diversity of its electrical patterns. When you are awake, the patterns tend to be richly varied and dynamic, while deep anesthesia or coma often shows more repetitive and predictable waves. In experiments, when this complexity drops below a certain range, people behave as if they are unconscious, and when it rises again they can report experiences. Still, failures and odd cases keep showing up, reminding us that using brain signals to declare someone completely unaware is more like reading a weather forecast than a mathematical proof.

Near‑Death Experiences And The Last Burst Of Brain Activity

One of the most haunting questions is what happens to awareness at the brink of death, when the brain’s energy supply collapses. Over the last decade, researchers have recorded brief, intense bursts of highly organized brain activity in humans and animals in the moments just before or just after the heart stops. Instead of a gentle fading out, some brains show a last dramatic flare of fast, coordinated signals that can look more “awake” than the resting state. This has led to speculation that some of the vivid near‑death experiences people report could be rooted in this final neuroelectric storm.

People who are resuscitated after cardiac arrest sometimes describe powerful experiences of clarity, presence, or altered perception, even though their clinical condition suggested deep unresponsiveness at the time. While personal accounts cannot prove what awareness “really” was doing then, they line up intriguingly with these recorded surges of brain activity. The emerging view is not that the soul leaves the body or anything so easily packaged, but that the dying brain may briefly enter a highly unusual, hyper‑organized state before finally going quiet. Whether that state feels like anything at all if no one survives to describe it is a question we may never fully answer.

Anesthesia, Locked‑In States, And The Risk Of Hidden Awareness

General anesthesia is supposed to switch off your awareness of surgery, pain, and the passage of time, yet research shows that a small but real number of patients later recall fragments of what happened. In many of these cases, the person couldn’t move, speak, or signal distress, but some part of their mind was still forming impressions. That’s a chilling thought: to be there, hearing and feeling, with no way to tell anyone. Modern anesthesia monitoring has improved, but it isn’t foolproof, and awareness under anesthesia remains one of the most feared complications in operating rooms.

Locked‑in syndrome adds another layer to the story, because in that condition the person is fully conscious but almost completely paralyzed, often able to move only their eyes. For years, some locked‑in patients were misdiagnosed as vegetative or minimally conscious because they couldn’t respond in the usual ways. Brain imaging and careful bedside observation eventually revealed that they were aware and following conversations despite their silence. These cases are a harsh reminder that external behavior is not a perfect mirror of internal awareness, and that a quiet body or a flat face can hide a thinking, feeling mind.

Anesthesiologists now use combinations of gas concentrations, brain‑activity monitors, and careful observation to reduce the risk of awareness, but there’s no absolute guarantee. There are also reports of “dream‑like” experiences between levels of anesthesia that don’t always match recorded depth levels. In my own life, after one minor surgery, I woke with a strong sense that I’d been present and dreaming right up until someone said my name, even though the staff insisted I’d been “fully under” the whole time. Experiences like that, multiplied across thousands of patients, keep pushing researchers to refine how they measure and manage true unconsciousness.

Does Awareness Linger In Coma And Vegetative States?

For families at a hospital bedside, the most painful question is whether their loved one in a coma or vegetative state has any awareness at all. Behaviorally, these patients may show only reflexes: opening eyes, random movements, changes in breathing, but no clear sign of understanding or intention. Yet over the last fifteen years, brain‑scanning studies have revealed that a significant minority of patients who appear entirely unresponsive actually show patterns of activity consistent with following instructions. For example, when asked to imagine playing tennis or walking through their home, certain brain areas light up in ways that match healthy volunteers doing the same mental tasks.

This so‑called covert consciousness forces clinicians to rethink diagnoses like “vegetative state,” because some of these individuals do have a form of inner awareness, even if they cannot express it outwardly. At the same time, not all patients show these signs, and the presence or absence of such patterns can change over time as the brain heals or deteriorates. The medical and ethical stakes are enormous: decisions about continuing life support, rehabilitation, and pain management all hinge on what we think is happening in that silent mind. The more we look, the more we discover that the border between awareness and its absence is a messy, shifting frontier, not a clean, sharp line.

Big Theories: Is Consciousness A Switch, A Spectrum, Or Something Else?

To make sense of these strange and sometimes contradictory findings, scientists have proposed several big theories about what consciousness fundamentally is. Some view it as a form of complex information integration, where awareness arises when many parts of a system both differentiate and share information deeply. Others emphasize global broadcasting, where certain pieces of information become widely available across the brain at once, turning private local events into something we can report and remember. Still others focus on the dynamics of prediction, treating consciousness as the brain’s ongoing attempt to anticipate the world and itself. None of these ideas has won, but each explains different pieces of the puzzle when the brain goes quiet.

One implication of these theories is that awareness might not be an all‑or‑nothing switch but more like a dimmer with many subtle settings. Under deep sleep, anesthesia, or coma, the “brightness” may fall so low that we can’t form memories or respond, yet small islands of structured activity could still generate fleeting or fragmentary experiences. That would explain why people sometimes recall sensations or dreams from periods where their brain looked very suppressed overall. If that view is right, the question “Does awareness stop?” might be too simple, and we should ask instead “How much, and in what form, does it persist?” The frustrating part is that direct access to those inner states is always blocked, leaving us to infer them from scattered clues.

The Unfinished Story Of A Silent Brain

When the brain falls silent on our instruments, what happens to awareness is still partly hidden from us, but the evidence so far points away from a clean on‑off switch. Many situations we once treated as complete unconsciousness – deep anesthesia, certain comas, early moments after cardiac arrest – turn out to contain more complexity and, in some cases, more inner life than we expected. A quiet EEG or a still body does not always mean an empty mind, and the rare cases of covert awareness have changed how medicine approaches diagnosis, monitoring, and end‑of‑life choices. At the same time, truly irreversible brain failure, where large portions of the brain are destroyed or no longer metabolically active, remains strongly linked to the end of any meaningful awareness.

Living in 2025, we sit in a strange position: we can watch the living brain with more precision than any generation before us, yet the core feel of awareness is still something we know only from the inside. Personally, I find it both sobering and oddly comforting that our minds do not simply vanish the moment the brain’s activity changes shape; there is a whole twilight zone between bright waking and total darkness. As research continues, we may learn how to better honor that hidden territory, especially for those who cannot speak for themselves. For now, every time you drift into sleep or wake from anesthesia, you are quietly rehearsing one of the deepest riddles we have: what actually happens when the lights, slowly or suddenly, go out?