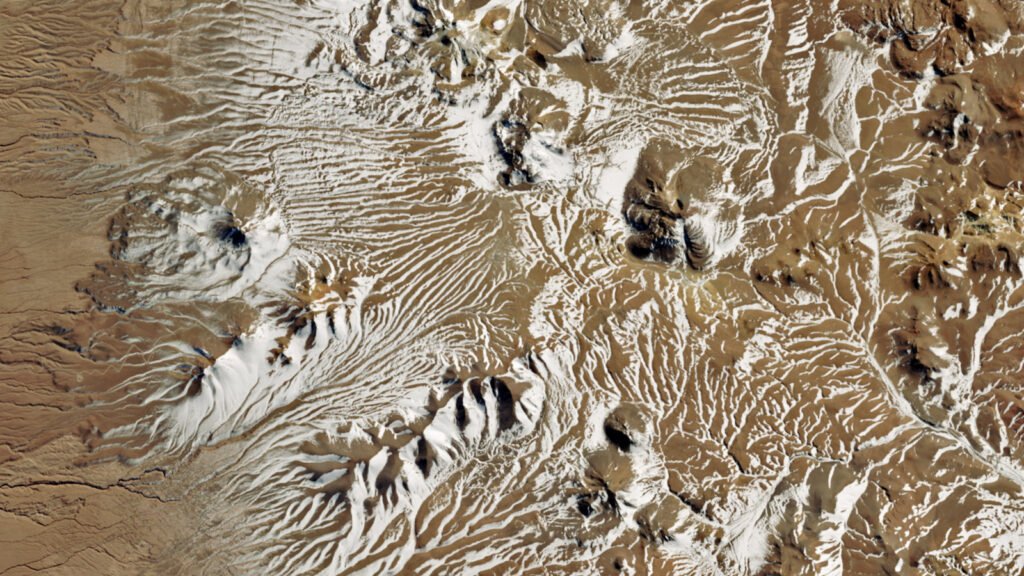

In a stunning and highly unusual weather event, the Atacama Desert—long known as one of the driest places on Earth—received a rare dusting of snow that was striking enough to temporarily shut down the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) observatory in northern Chile. Satellite imagery captured by Landsat 9 shows broad swaths of white across a landscape typically famed for its barren, bone-dry terrain, revealing how exceptional this episode truly was.

The snowfall occurred in mid-July 2025, blanketing both the desert floor and the high-altitude Chajnantor Plateau at more than 16,000 feet above sea level. ALMA’s operations were placed into “survival mode” as technicians moved equipment to protect it from the unexpected precipitation and extreme cold. While the snow melted or sublimated by mid-July, the impact on scientific activity was unmistakable, illustrating how even the most arid regions of the planet are not immune to rare, extreme winter weather.

A Desert Unlike Any Other

The Atacama Desert in northern Chile is the oldest and driest non-polar desert on Earth, with some parts of its hyperarid core receiving less than a millimeter of rain annually. Its extreme dryness results from a combination of geographic and climatic factors, including the rain shadow of the Andes Mountains and the cool upwelling waters of the Pacific Ocean, which suppress cloud formation and precipitation.

This unforgiving environment has long made Atacama an ideal site for astronomical observation, boasting some of the clearest and most stable skies on the planet—perfect for telescopes like ALMA that depend on minimal atmospheric moisture. Yet even this extraordinary desert occasionally buckles under unusual weather patterns, as evidenced by the mid-July snowfall that veiled its sandy plains in white.

How Rare Snow Formed in the Atacama

Meteorologists linked the rare snowfall to a cold-core cyclone moving through northern Chile, which drew moisture into the region and caused temperatures to dip sharply below normal for the season. Snow fell not only on the high plateau but also in areas that rarely, if ever, see frozen precipitation. Such events have only been recorded a handful of times in recent decades, including notable snows in 2011, 2013, and 2021.

These anomalous storms suggest a growing complexity in the atmospheric dynamics of the region. Some scientists believe that climate change could be increasing the frequency or intensity of such rare precipitation events, even in places as historically arid as the Atacama.

Telescopes in the Snow

Atacama is home to numerous world-class observatories because its dry air and high altitude create near-ideal observing conditions. ALMA, in particular, is a collaborative international facility consisting of 66 high-precision radio antennas that work together to study the universe at millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths.

When the snowfall hit, ALMA’s operators had to suspend scientific observations to protect sensitive equipment and ensure personnel safety at the high-altitude camp. The array’s antennas were reoriented to minimize snow buildup, and technicians began preparations to resume operations as soon as conditions allowed.

Impacts Beyond Astronomy

The snowstorm didn’t just affect telescopes: heavy precipitation associated with the same weather system caused rainfall and winds in northern Chile, prompting alerts from the Chilean Meteorological Directorate. Although no casualties were reported, the event led to power outages, school closures, and localized infrastructure strain.

This sequence of events underscores how rare weather in hyperarid regions can have disproportionate effects—from disrupting cutting-edge science to challenging local infrastructure unaccustomed to handling such conditions.

What This Means for Climate and Science

The juxtaposition of desert dryness with occasional snow raises important questions about how climate variability is influencing even the most extreme environments. While such snowfalls are still exceptionally rare, their recurrence over the past decade hints at shifting weather patterns that may be tied to broader atmospheric changes.

For the scientific community, these episodes are both a challenge and an opportunity: they highlight the importance of building resilience into our infrastructure and studying how rare weather events might affect long-term research projects in sensitive regions like Atacama.

The rare snowfall over the Atacama Desert—an area usually synonymous with everlasting dry heat—is a vivid demonstration that no part of our planet is entirely predictable or immune to extreme weather. Beyond its immediate impact on world-class astronomy facilities like ALMA, this event hints at deeper, perhaps climate-linked shifts that require serious attention from both scientists and policymakers. As climate systems warm and the air holds more moisture, even deserts may occasionally experience the unthinkable. While isolated events don’t define a trend, they should prompt deeper investigation into how weather extremes are reshaping the planet’s most iconic landscapes—and how human activity might be contributing to these changes.