Earth looks solid and familiar from where we stand, but its story is one of chaos, collision, and reinvention on a planetary scale. Over billions of years, a series of violent, often invisible geological events have turned a molten rock ball into the only known home for life in the universe. Scientists are still piecing together this deep-time crime scene, using fragments of rock and chemistry as their clues. The more they uncover, the clearer it becomes that events we can barely imagine still echo in our continents, oceans, and even the air we breathe. Understanding these ancient upheavals is not just an academic exercise – it is a way of reading the script for Earth’s future.

The Giant Impact: When A “Second Planet” Built The Moon

It is hard to imagine, but the calm Moon that lights our nights was likely born from one of the most catastrophic days in Earth’s history. Around four and a half billion years ago, a Mars-sized protoplanet – nicknamed Theia – probably slammed into the young Earth at a glancing angle, vaporizing rock and spraying molten material into space. That debris eventually coalesced into the Moon, while Earth itself was remixed, heated, and stripped of some of its early atmosphere. I remember staring at a simulation of that impact for the first time and feeling a jolt of vertigo, realizing our entire sky is a fossil of that one impossible moment. It is an origin story that feels more like science fiction than geology.

The evidence is written in chemistry: lunar rocks brought back by astronauts have isotopic fingerprints almost indistinguishable from Earth’s mantle, hinting at a shared, violent origin. Without this impact, Earth might have spun too fast, tilted too wildly, or lacked the stabilizing gravitational partner that has helped regulate tides and climate over billions of years. Some researchers even argue that the Moon’s influence on tides and rotational stability may have been crucial in giving complex life a chance. In that sense, the collision that should have destroyed our world may have ended up making it uniquely habitable.

The Magma Ocean: When Earth Was A Planet Of Fire

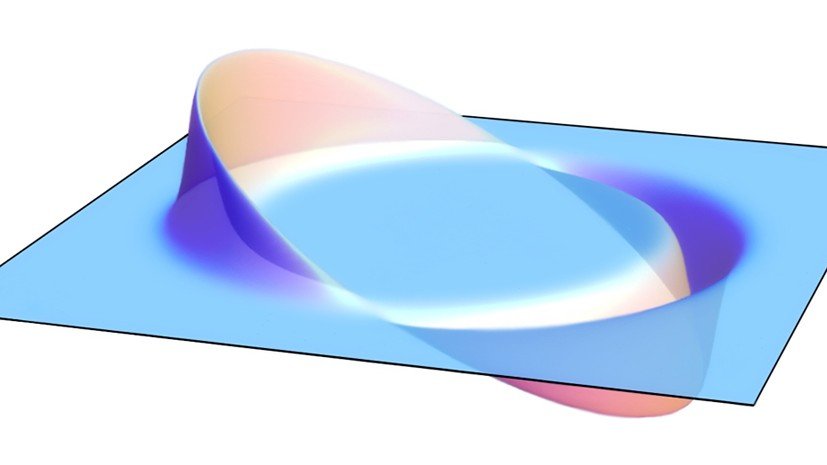

Before continents, before oceans, before even a solid crust, Earth was probably a shimmering sphere of molten rock – a global magma ocean. The energy from constant asteroid impacts, radioactive decay, and that giant collision kept the surface so hot that rock behaved more like thick syrup than stone. If you could have hovered above the planet then, you would have seen a hellish world glowing red-orange with erupting plumes and boiling vapor, with no safe place to stand. It is a phase we cannot witness directly, but its legacy is locked deep below our feet, in the structure of Earth’s interior.

As that magma ocean slowly cooled, heavier elements like iron and nickel sank toward the center, while lighter silicate materials floated upward to form the first primitive crust. This separation, called differentiation, created the layered planet we know today: core, mantle, and crust, each with its own role in driving magnetic fields, plate tectonics, and volcanism. Hidden within the mantle, seismic studies have uncovered strange, ultra-dense regions that may be relics of that early molten era. They act like geological ghosts, quietly affecting how heat rises and where supervolcanoes may someday appear. Our solid-looking world, it turns out, was born from a long, turbulent age when rock moved like water.

The Great Oxygenation Event: When Microbes Rewired The Atmosphere

Roughly a couple of billion years ago, tiny microbes pulled off a planetary-scale engineering feat that no human technology has ever matched. Cyanobacteria – simple, photosynthetic organisms – began pumping out oxygen as a waste product, gradually transforming Earth’s atmosphere from a toxic, oxygen-poor mix into something closer to what we breathe today. At first, that oxygen reacted with iron in the oceans and crust, staining ancient rocks with rusty-red bands that geologists still marvel at. Only after those sinks were filled did oxygen begin to accumulate in the air in a significant way.

This so-called Great Oxygenation Event was a double-edged sword. For many anaerobic organisms, oxygen was poisonous, and entire branches of life were pushed into hidden niches or extinction. But for others, this new gas became a powerful fuel, enabling more energy-hungry metabolisms and paving the way for complex, multicellular life. The atmosphere itself shifted from a greenhouse-dominated world to one where ozone could form, shielding the surface from harmful radiation. It is striking to realize that what we think of as “normal” air is actually the outcome of a radical biological experiment run by microbes long before animals appeared. In a sense, the first major geoengineers on Earth were bacteria, not humans.

The Birth Of Plate Tectonics: When The Crust Learned To Drift

One of the most mind-bending ideas in Earth science is that the ground beneath us is not fixed at all – it is a set of colossal, interlocking plates slowly gliding atop a softer mantle. Plate tectonics did not start on day one; it likely emerged once Earth’s crust cooled enough to fracture but the interior stayed hot and convecting. Over immense spans of time, this system has recycled seafloor, built mountains, and stitched and ripped apart continents. Standing in front of a crumpled mountain chain, it is hard not to see them as the wrinkles left by colliding plates.

Geologists now know that Earth’s history includes multiple cycles of supercontinents – Rodinia, Pannotia, Pangaea – forming and breaking apart. Each cycle rearranged climates, sea levels, and habitats, reshuffling the deck for evolution. Compared with a hypothetical “stagnant lid” planet where the crust never moves, Earth’s restless plates help regulate long-term climate by burying carbon, forming volcanoes, and exposing fresh rock to weathering. That constant renewal might be one key reason our world has stayed habitable for billions of years while others, like Mars, appear geologically frozen. Plate tectonics turns the solid Earth into a kind of slow-breathing organism, inhaling and exhaling heat and chemistry over deep time.

The Snowball Earth Episodes: When The Planet Nearly Froze Solid

Twice in the distant past, Earth seems to have swung to the opposite extreme from its magma-ocean youth, entering what researchers call Snowball Earth episodes. Evidence from glacial deposits found near ancient tropical latitudes suggests that ice sheets may have advanced almost to the equator. Imagine standing on a shoreline where the entire horizon is frozen, oceans locked down under kilometers of ice, with only thin cracks of open water near volcanoes or tectonic rifts. It is a chilling reminder that our climate system is capable of far more dramatic shifts than anything in recorded history.

Paradoxically, these global deep-freeze events may have helped set the stage for the rise of complex life. With so much ice reflecting sunlight, Earth likely cooled until volcanic carbon dioxide built up in the atmosphere to extraordinary levels. When the freeze finally broke, intense greenhouse warming would have triggered catastrophic melting, torrential rains, and rapid erosion, flooding oceans with nutrients. Those nutrient pulses may have fueled evolutionary bursts in the aftermath. The scars of these frozen ages, preserved in rocks, offer a stark warning about how feedback loops can push the climate system into unfamiliar and extreme states.

The Permian–Triassic Mass Extinction: When Earth Nearly Lost It All

Roughly about a quarter of a billion years ago, Earth went through what some scientists bluntly call the Great Dying. During the Permian–Triassic mass extinction, the vast majority of marine species and a huge share of land species vanished in a geologically brief window. Many researchers link this catastrophe to gigantic volcanic eruptions in what is now Siberia, where lava flows and gas emissions persisted for hundreds of thousands of years. The atmosphere filled with carbon dioxide, methane, and toxic compounds, driving temperatures sharply higher and turning parts of the oceans anoxic and acidic.

What makes this event especially unsettling is how it unfolded as a cascade: warming led to ecosystem collapse, which disrupted carbon cycling, which in turn fueled even more warming. In some rock layers, you can see this disaster recorded as a sharp transition from rich, diverse fossil assemblages to almost barren sediments. Drawing too simple a parallel to today would be misleading, but studying this ancient crisis gives scientists a sobering point of comparison for rapid climate change driven by greenhouse gases. The planet did eventually recover, and the age of dinosaurs followed, but it took millions of years for diversity to rebound. From a human perspective, that kind of recovery time might as well be forever.

The Chicxulub Impact: The Day The Dinosaurs’ World Ended

Sixty-six million years ago, a chunk of space rock roughly ten kilometers across slammed into what is now the Yucatán Peninsula, and Earth’s history pivoted in a single, terrible day. The Chicxulub impact released an energy equivalent to billions of nuclear bombs, generating shock waves, wildfires, tsunamis, and a global dust cloud that darkened the skies. Dinosaurs that were not already wiped out by the blast and heat faced a collapsing food web as sunlight dwindled and plants died back. When I visited the edge of that buried crater region, it was surreal to think that under quiet villages lay the scar from one of the most infamous days on Earth.

Geologists found the smoking gun in a thin clay layer worldwide enriched in iridium, a metal rare in Earth’s crust but common in asteroids. Drilling projects into the crater itself have revealed deformed rocks and melted glass that confirm just how violent the impact was. Beyond its cinematic destruction, the Chicxulub event opened ecological space for mammals and, ultimately, humans to thrive. Without that asteroid, the age of dinosaurs might have continued, and primates could have remained small and obscure. It is a stark reminder that chance cosmic events can redirect the entire trajectory of life.

Why These Events Matter: Reading Earth’s Past To Understand Our Future

It is tempting to file these geological epics under distant history, safely disconnected from the present, but that would be a mistake. Each of these events reshaped climate, chemistry, and life in ways that echo into today’s world, from the oxygen we breathe to the layout of our continents. Traditional views once imagined Earth as a mostly unchanging backdrop, but modern geology has replaced that picture with a restless, dynamic planet driven by feedbacks and thresholds. Mass extinctions, runaway warming, and global glaciations are not just abstract possibilities – they are chapters that have already played out.

Compared with earlier eras, we now have tools to measure atmospheric gases, track plate motions, and model deep-time climate with far greater precision. That lets scientists ask sharper questions: How close are we to triggering similar tipping points? How resilient is the biosphere to rapid change? By comparing today’s human-driven shifts with events like the Great Oxygenation or the Permian crisis, researchers can identify both alarming parallels and crucial differences. To me, this is where the story turns from awe to responsibility. If we can read the warnings in the rocks, we cannot pretend we were not told how the story can go wrong.

The Future Landscape: Supercontinents, Supervolcanoes, And Human Choices

Looking ahead, Earth is not done reinventing itself. Plate tectonics will keep shuffling the continents, and models suggest that in a few hundred million years, a new supercontinent – sometimes dubbed Aurica or Pangaea Ultima, depending on the scenario – could form. Such a configuration would radically rearrange ocean currents, monsoons, and climate patterns, likely creating harsh, hot continental interiors and new, vulnerable coastlines. Deep in the mantle, long-lived plumes will continue to feed volcanic hotspots, some of which could erupt in rare but devastating supervolcano events.

On shorter timescales, the most rapid and unpredictable force acting on the planet is us. Our emissions, land use, and resource extraction are shifting climate and ecosystems at rates that rival some past geological crises, but compressed into centuries instead of millennia. At the same time, new technologies – from satellite gravimetry to deep-sea drilling and planetary seismology – are giving scientists an unprecedented view into Earth’s interior and its long-term cycles. These tools may help forecast hazards, from megathrust earthquakes to volcanic unrest, more accurately than ever before. Whether the next chapter is one of adaptation and foresight or of avoidable turmoil will depend heavily on how seriously we treat the lessons embedded in deep time.

What You Can Do: Tuning Into A Restless Planet

It is easy to feel small in the face of billion-year processes and planet-sized disasters, but engaging with Earth’s story does not require a lab or a research grant. You can start by simply paying attention: visit a local outcrop, a canyon, or even a city rock garden and try to imagine the forces that shaped those layers. Support science education programs and museums that bring geology to life for kids who might otherwise never hear about plate tectonics or mass extinctions. When debates arise about climate policy, mining, or land use, remember that these choices are entangled with the same systems that built supercontinents and carved oceans.

On a more direct level, reducing your own carbon footprint, backing conservation efforts, and supporting organizations that monitor natural hazards all help align human activity with the realities of a dynamic planet. Even small steps – switching to cleaner energy where possible, voting with Earth’s long-term health in mind, staying informed about local geological risks – add up when many people make them. The rocks record an Earth that will keep changing with or without us. The real question is whether we choose to become careful readers of that record or remain surprised by chapters we could have seen coming.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.