Long before telescopes and space probes, people stared up at the same planets we see today and filled the darkness with stories. To them, those wandering lights were not dead rocks but volatile gods, lovers, warriors, and omens that could tilt the fate of empires. Today, planetary science can model atmospheres, trace orbital resonances, and simulate early solar system chaos – yet the myths that named Mars, Venus, or Jupiter still quietly shape how we talk and even think about them. When you look closely, those ancient stories become more than superstition; they are early theories of motion, color, brightness, and time. And strangely, once you start lining them up with what we now know about each planet, the match is sometimes unnervingly close.

The Hidden Clues: Why Did So Many Cultures Turn Mars into a God of War?

The idea that Mars is the planet of war is so familiar it feels inevitable, but that is already a clue: different cultures, from the Greeks and Romans to some Mesopotamian traditions, all fixated on Mars as a violent cosmic actor. They did not know about iron oxide dust or thin carbon dioxide air, yet they saw a star that flared red like fresh blood, sometimes dim, sometimes suddenly brighter, and moving against the calmer background of the night sky. To sky-watchers used to slow, stable stars, that erratic ruby wanderer demanded an explanation, and war – chaotic, fiery, unpredictable – fit the bill. In a way, assigning Mars to warfare was an early attempt at pattern matching, a human brain trying to link color and motion to meaning. When you learn that the surface really is rust-red and that the planet likely had a more violent, water-rich past, you can almost hear those first storytellers saying, without data but with conviction, that this was not a peaceful place.

From a modern perspective, Mars’s mythology has gone through a quiet rebrand: we now talk less about battle and more about exploration and survival. The same planet that once meant conquest in myth now hosts rovers tracing dried river deltas and dust devils on the horizon, hinting at lost oceans and maybe, long ago, life. Yet we still borrow the old language of conflict – mission “campaigns,” “frontiers” to conquer, even “colonization” – which shows how sticky those early warlike associations remain. Mars taught early humans that color in the sky might matter, and now it teaches us that barren landscapes can hold climate histories more dramatic than any legend. The planet of war has become the planet of questions, but its old name still glows behind the scenes like an ember under ash.

Venus the Morning Star: How Did One Planet Become a Symbol of Love and Doom?

It is easy to assume Venus was tied to love and beauty simply because it shines so brightly, but the story is stranger and sharper than that. For many ancient cultures, Venus was both the gentle morning star that heralded dawn and a fierce evening star that lingered after sunset, so bright it could cast shadows. Some traditions even treated these two appearances as different beings, then later realized they were the same wandering light, merging dual deities into a single complex figure. That double life – soft and luminous yet striking and sometimes ominous – made Venus a natural symbol for desire: captivating, transforming, and occasionally destructive. The sky taught a lesson that every society intuitively understood on the ground: what dazzles you can also burn you.

Modern planetary science reveals that under that beautiful brightness is a world almost designed to crush illusions. Venus’s thick atmosphere traps heat so ruthlessly that its surface can melt lead, with pressure that would flatten a submarine and clouds dripping sulfuric acid. The planet that looked like a cosmic jewel turned out to be a runaway greenhouse, a nightmare version of climate gone off the rails. That twist gives the old myths an eerie new relevance, because the same star once linked with love and fertility now serves as a cautionary tale for climate change on Earth. We still watch Venus at twilight, but now scientists also read it as a warning label written in planetary chemistry instead of poetry.

Jupiter the Sky King: What Made This Giant the Prototype of a Cosmic Ruler?

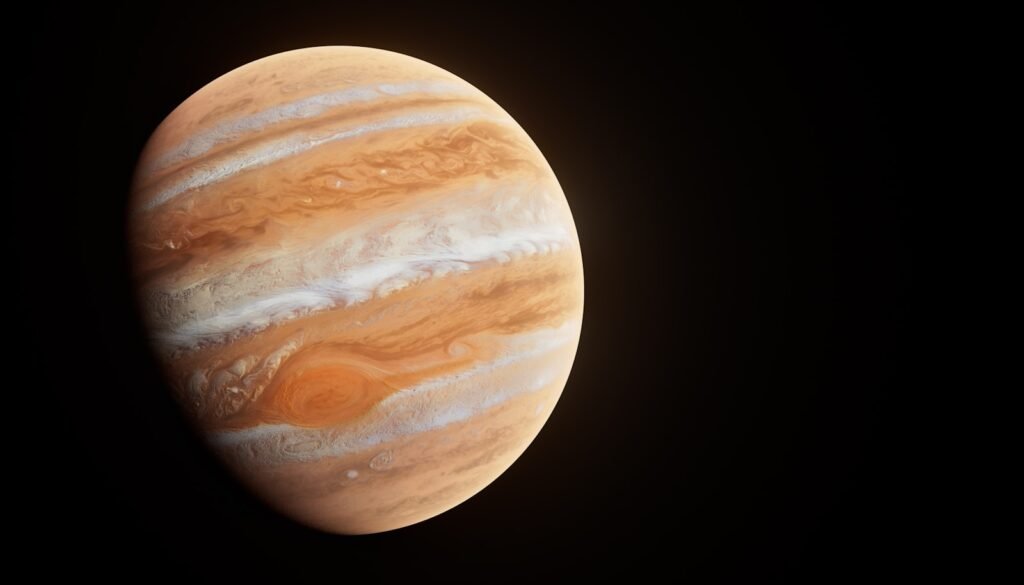

Look up on a clear night when Jupiter is high and you can see why early sky-watchers felt it had authority. It is one of the brightest points in the sky, steady rather than sparkling, gliding with serene confidence along the ecliptic path. Many cultures gave their chief gods to this planet – the Romans had Jupiter, the Greeks Zeus, others linked it with thunder, judgment, or order – because a big, calm, predictable light felt like a natural anchor in a chaotic sky. Its long, stately loop against the background of stars suggested patience rather than frenzy, like a ruler who does not need to rush. Even without instruments, people could sense that Jupiter was not just another star in the crowd.

Now we know that gravitationally, the ancient instinct was right on target. Jupiter’s enormous mass helps sculpt the entire solar system, nudging asteroids, deflecting some comets, and possibly shielding Earth from frequent catastrophic impacts. Its bands and storms, especially the Great Red Spot, are like visual proof that power does not always look smooth up close; even a “king” planet is a boiling fluid world of jet streams and lightning. Spacecraft flybys have shown moons with oceans beneath ice and volcanoes spewing plumes into space, making Jupiter more of a miniature solar system than a lone planet. Those early myths that crowned it as ruler captured something very real: if you follow the invisible threads of gravity, Jupiter sits at the center of many of them.

Saturn’s Rings and the Idea of Boundaries: How Did a Hidden Feature Inspire Tales of Time and Fate?

Most early humans never saw Saturn’s rings as we do now; to the unaided eye, Saturn is a pale, slow-moving point of light. Yet cultures repeatedly linked it to time, age, and strict limits – an old god with a scythe, a marker of boundaries, a bringer of endings as much as harvests. Part of this comes from Saturn’s sluggish motion: it takes nearly three decades to complete one lap through the zodiac, so anyone tracking it over years would sense its cycle as a backdrop to a human life. If you grew up in an era when careful observation of the sky guided planting, taxation, and festivals, a planet that moved so slowly would naturally become a clock of last resorts. It made a strange kind of sense to put responsibility for fate and deadlines into Saturn’s hands.

Telescopes later turned that austere point into the most visually dramatic object in the solar system, revealing glowing rings made of ice and rock circling in razor-thin sheets. Suddenly, the planet of limits literally wore a gigantic boundary, a cosmic hula hoop of frozen particles constrained by gravity and orbital resonances. Those rings are constantly recycled, ground down, and reshaped, a reminder that even seemingly fixed edges are dynamic systems. Today, Saturn still teaches scientists about how disks form and evolve, from young planetary systems to the debris around black holes. The timekeeper of myth now helps time the lifespans of rings, moons, and orbits, turning ancient fears of fate into equations and simulations.

Mercury the Swift Messenger: What Does a Racing Dot Tell Us About Motion and Mind?

Mercury is easy to miss if you are not looking for it, but once you spot it hugging the horizon at dawn or dusk, its behavior explains a lot of old stories. It darts in and out of view, never straying far from the Sun, vanishing for days or weeks and then reappearing on the opposite side of the sky. Ancient astronomers had to work hard to follow its path, and many associated it with quick-thinking deities, tricksters, or messengers darting between realms. That made poetic sense: a flickering point that shows up briefly with news of a new day or fading light feels like a cosmic courier. When something is that elusive, you start assuming it knows secrets you do not.

Modern data show that Mercury really does live a frantic life compared with its neighbors. It races around the Sun in just under three months, locked in an unusual spin–orbit resonance that means its day and year follow a strange, repeating pattern. Its iron-rich core and battered surface tell a story of violent impacts, lost crust, and a thin exosphere constantly blasted by solar radiation. For scientists, Mercury is a laboratory for extremes in temperature and gravity, but emotionally, it still carries that old reputation for restlessness. The planet of messages now delivers different news: clues about how inner rocky worlds form, behave, and slowly cool under the relentless glare of their stars.

The Outer Wanderers and the Edge of the Map: How Uranus and Neptune Challenged Myth Itself

Unlike Mars or Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune slipped beneath the radar of ancient mythmakers simply because they are too faint to stand out to naked eyes. By the time they were discovered with telescopes in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the old planetary pantheon was already crowded, so astronomers deliberately reached back into classical names to fold them into a familiar story. Uranus became a sky god, Neptune a sea deity, even though no culture had tied them to regular omens or seasonal cycles before. In a way, this was mythworking in reverse: instead of people building stories around a visible light, scientists attached existing stories to newly measured points in the dark. These planets marked the first time that calculation and instrumentation expanded the cosmos faster than inherited legends could keep up.

The scientific shock they delivered was enormous. Uranus’s odd axial tilt and Neptune’s gravitational tug helped confirm that Newtonian physics could predict unseen worlds, while their bluish colors revealed atmospheres rich in hydrogen, helium, and methane. They hinted that the solar system was not a tidy arrangement of a few familiar gods but a sprawling structure full of icy giants and distant belts. Later, the discovery of Pluto, dwarf planets, and Kuiper Belt objects pushed that frontier even farther, out to places that never earned formal roles in any myth at all. If older planets taught humans to tell stories about what they could see, Uranus and Neptune quietly taught us that reality does not need to fit the stories first.

Why It Matters: Planetary Myths as the First Models of the Universe

It is tempting to treat planetary myths as cute cultural relics, but they were also serious attempts to model a terrifyingly complex sky with the tools available at the time: memory, metaphor, and shared narrative. Before mathematics could describe elliptical orbits, people noticed patterns – retrograde loops, brightening and dimming, seasonal returns – and encoded those regularities into tales of battles, romances, or divine errands. These narratives functioned like early data visualizations, compressing years of sky-watching into a story you could retell by a fire or inscribe in temple walls. Compared with modern orbital mechanics, the explanations were wrong in detail, but they were right in spirit: they assumed that the movements were not random, that there was an underlying order worth decoding. That assumption is the root of science itself.

Today, researchers in fields like archaeoastronomy and anthropology unpack these myths not to debunk them but to read the observations hiding inside. When multiple cultures independently link a planet’s color or periodic appearance to certain events, it hints at what was most visible and meaningful to human eyes in different environments. It also reveals how people used the sky as a shared clock and calendar before standardized timekeeping, guiding agriculture, navigation, and ritual. Understanding these stories is not about choosing myth or science; it is about seeing them as consecutive layers in the same long investigation. The planets have not changed much in a human lifetime, but our ways of explaining them have, and that evolution says as much about us as it does about the cosmos.

From Stories to Spectrometers: How Science Is Rewriting Planetary Legends

In the last few decades, spacecraft flybys, orbiters, and landers have taken us from poetic guesses to high-resolution maps and elemental breakdowns of planetary surfaces. Mars is no longer only the god of war but a dusty archive of riverbeds, deltas, and mineral veins that point to ancient lakes. Venus has gone from a symbol of beauty to a sobering example of what happens when greenhouse gases spiral far beyond any hope of balance. Jupiter and Saturn are now known not just as dignified sky markers but as restless worlds with magnetic fields screaming with radio emissions and moons that may hide subsurface oceans. Each new dataset revises the old image without erasing it completely.

For many scientists I have spoken with over the years, there is a quiet awareness that public fascination often begins with the mythic frame. People are drawn in by the idea of the love planet, the war world, the ringed timekeeper, then stay for the complex atmospheric models and seismic data. Outreach programs routinely lean on familiar names and stories because they make a distant, airless rock feel part of a shared human heritage. In that sense, spectrometers and myths are collaborators, not rivals: one measures what is there, the other makes us care. The real challenge is to let updated evidence reshape the stories we tell, instead of forcing the universe to match the tales we inherited.

The Future Landscape: New Worlds, New Myths?

As exoplanet discoveries mount into the thousands, our old cosmic cast of characters suddenly looks like a tiny ensemble in a galaxy-spanning drama. Astronomers are finding planets that orbit two suns, worlds heavier than Jupiter but hotter than molten iron, and others that may be rocky, temperate, and shrouded in clouds. Future space telescopes are being designed to analyze the atmospheres of some of these distant planets, searching for gases that might hint at oceans, forests, or even industrial activity. In the process, we are going to encounter conditions so alien that our old familiar metaphors – war, love, kingship – may feel too small. The cosmos is about to force an update not just to our models but to our imagination.

There is a good chance that new cultural stories will emerge around these far-off worlds, just as they did for Mars or Venus, but shaped by data feeds and artist’s impressions rather than naked-eye viewing. Science fiction is already laying groundwork, turning exoplanets into backdrops for survival tales, political allegories, or philosophical puzzles. Education programs might soon teach children constellations that include not just star patterns but notable planetary systems with nicknames tied to their quirks. The myths we tell in the coming decades will not replace spectroscopy or orbital mechanics, but they will frame how whole generations emotionally relate to a universe that suddenly feels crowded. In that sense, mythmaking is not a leftover from the past; it is an ongoing response to discovery.

Seeing Ourselves in the Sky: How Readers Can Engage with Planetary Stories Today

You do not need a degree in astrophysics to participate in this long conversation between planets and people; you really just need eyes, curiosity, and a willingness to look up more often. Start by noticing how the bright “stars” that do not twinkle – planets – move over weeks and months, then compare what you see with simple sky charts or apps. Read how different cultures interpreted those same lights and notice which ideas feel strangely modern, which feel utterly foreign, and which echo fears or hopes you still recognize in yourself. When missions launch to explore these worlds, follow their progress and let the raw images challenge the stories you are used to hearing. The more fluent you become in both myth and measurement, the richer the night sky gets.

If you are moved by this blend of old stories and new science, there are direct ways to support it. You can back public observatories, museum programs, and science literacy initiatives that help kids connect the dots between legends and light curves. Citizen-science platforms sometimes invite volunteers to comb through telescope data, flagging potential exoplanet transits or unusual planetary weather patterns. Even small acts – sharing a sky event with a friend, attending a local star party, or advocating for dark-sky protections in your community – keep the tradition of communal sky-watching alive. The planets will continue their silent loops regardless, but how we choose to notice and narrate them is still very much up to us.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.