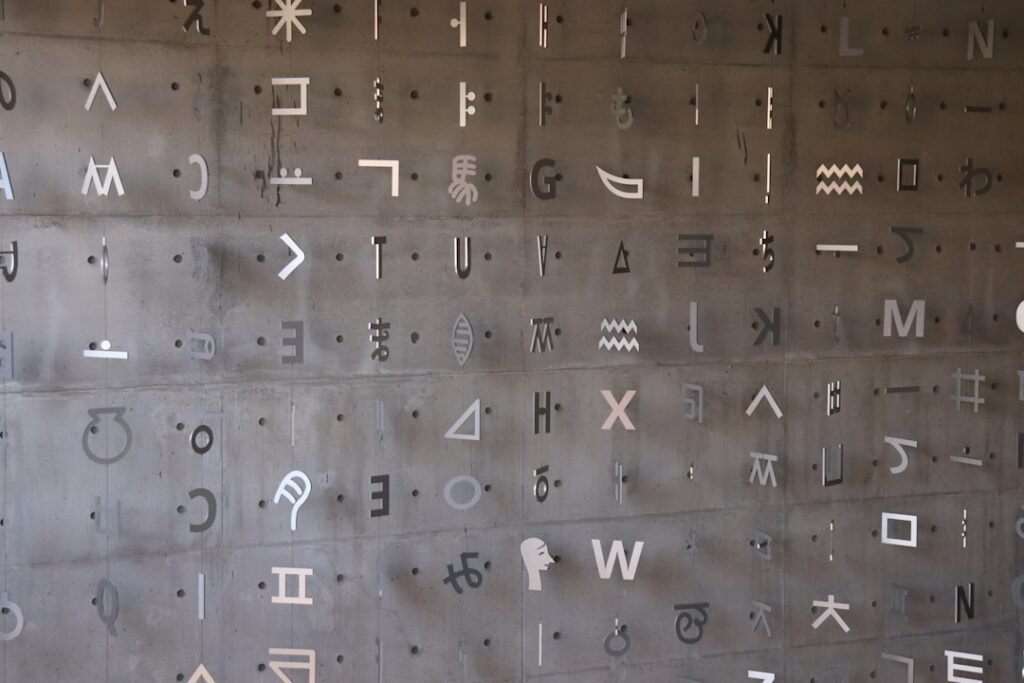

Have you ever wondered what secrets lie hidden in the symbols our ancestors carved into stone and clay thousands of years ago? Scattered across continents and locked away in museums, countless inscriptions whisper stories we can’t yet understand. Some were carved by civilizations that vanished so completely that even their languages disappeared with them. Others sit on tablets that survived fire, water, and centuries of neglect, yet remain as impenetrable as the day they were created.

These ancient codes tantalize you with the promise of forgotten knowledge. Maybe they contain sacred rituals, trade agreements, medicinal recipes, or astronomical observations. Perhaps they’re simply inventories of grain and livestock. The truth is, we don’t know, and that uncertainty is precisely what makes them so captivating. So let’s dive in and explore some of the most baffling writing systems that continue to elude humanity’s best efforts at decipherment.

The Indus Valley Script: A Civilization’s Silent Voice

You’re looking at remnants of one of the world’s most advanced Bronze Age civilizations, which sprawled across over 250,000 square miles in what is now Pakistan and northwest India between 2600 and 1900 BCE, boasting large, well-planned cities like Mohenjo-daro and a script no one has been able to understand. Imagine walking through those ancient streets where merchants traded with distant lands, where sophisticated drainage systems carried waste away from homes, and where people carved mysterious symbols onto small seals.

The challenge is immense because researchers have compiled between 400 and 700 distinct signs, and most inscriptions are rather brief, composed of an average of just four or five signs, while the longest example contains 30 characters. It’s like trying to understand a language when all you have are text messages with only a handful of words each. Success has eluded researchers because decipherments of other ancient scripts like Egyptian hieroglyphs relied on bilingual inscriptions such as the Rosetta Stone, but no such bilingual text has been found for the Indus script, depriving researchers of a key comparative framework.

Still, that hasn’t stopped people from trying. Recent research employing statistical analysis and AI-assisted pattern recognition has cross-compared Indus inscriptions with ancient scripts such as Oracle Bone Chinese, Egyptian Hieroglyphics, and writing systems from Mesopotamia, with evidence pointing toward a higher likelihood that the Indus script functioned as a logographic or morpho-syllabic system. Whether these computational approaches will finally crack the code remains to be seen, yet the allure of unlocking an entire civilization’s written record keeps scholars searching for that breakthrough.

Linear A: Crete’s Enigmatic Predecessor

Originating in ancient Crete during the Minoan civilization around 1800 to 1450 BCE, Linear A is the earliest script used to write the Minoan language, with symbols that are primarily linear in nature. You might recognize its younger sibling, Linear B, which was famously deciphered in the 1950s and revealed itself to be an early form of Greek. The older script, however, refuses to cooperate.

While Linear B was deciphered as an early form of Greek, Linear A remains a mystery and is believed to be a syllabic script, but the language it represents does not relate to any known language family, leaving its contents largely speculative. Think about that for a moment. We can actually read many of the symbols because they were borrowed for Linear B, but when scholars apply those sound values to Linear A texts, the results are gibberish. Since 1974, not enough new text has been added to make decipherment provable if the language it hides is unrelated to anything we already know, and even if it is hiding some language we already have a linguistic handle on, we are still scarcely up to the top of the hump.

The Minoans left behind spectacular palaces and vibrant frescoes, but their language stubbornly guards its secrets. Scientists believe these scripts used by ancient Minoans were used mostly for accounting and record-keeping purposes, yet the difficulty of translating them stems from a lack of adequate materials to translate. It’s frustrating, honestly. We can see the civilization’s grandeur, yet we can’t hear their voices.

Proto-Elamite: Iran’s Ancient Accounting System

The Proto-Elamite script is an early Bronze Age writing system briefly in use before the introduction of Elamite cuneiform, and it has not yet been completely deciphered. Emerging around 3000 BCE in what is now Iran, this script has left behind roughly 1,600 tablets, most discovered at the ancient city of Susa. Proto-Elamite is the last undeciphered writing system from the Ancient Near East with a substantial number of sources, and it was used for a relatively short period around 3000 BC across what is today Iran.

Here’s what makes it fascinating: There are many similarities between the Proto-Elamite tablets and contemporaneous proto-cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamia, including the tablet blanks themselves, the inscribing method, even the practice of using the reverse for summation, all serving the same basic function of administrative accounting of goods in a centrally controlled society. Yet despite these similarities, the scripts themselves are different enough that Proto-Elamite has resisted translation.

While the Elamite language has been suggested as a candidate underlying the Proto-Elamite inscriptions, there is no positive evidence of this, and the earliest Proto-Elamite inscriptions, being purely ideographic, do not in fact contain any linguistic information. So you’re essentially looking at a sophisticated accounting system that tracked goods and labor, but without knowing what language the accountants actually spoke. Most recent advances have resulted from a new understanding of the structure of the numerical sign systems, which has provided a powerful tool for semantic identification of ideograms including those for grain products, animals, and possibly human beings.

Rongorongo: Easter Island’s Vanishing Knowledge

Let’s be real, Easter Island is already mysterious enough with its massive stone heads staring out across the Pacific. Now add an undeciphered writing system that may have been one of only a few independent inventions of writing in human history, and you’ve got yourself a proper enigma.

Rongorongo is a system of glyphs discovered in the 19th century on Easter Island that has the appearance of writing, numerous attempts at decipherment have been made but none have been successful, and if it proves to be writing and to be an independent invention, it would be one of very few inventions of writing in human history. The script is written in a bizarre pattern called reverse boustrophedon, which means you start at the bottom left, read to the right, then flip the tablet upside down and read the next line.

The tragic part of this story is the loss of knowledge. Given that few if any of the Rapanui people remaining on the island in the 1870s could read the glyphs, it is likely that only a small minority were ever literate, and early visitors were told that literacy was a privilege of the ruling families and priests who were all kidnapped in Peruvian slaving raids or died soon afterward in the resulting epidemics. Within a single generation, the ability to read Rongorongo vanished. Recent radiocarbon dating found one specimen yielded a unique mid-fifteenth century date, suggesting that the use of the script could be placed to a horizon that predates the arrival of external influence.

Today, just 27 wooden objects inscribed with Rongorongo exist, and none of them remain on the island of Rapa Nui. They sit in museums around the world, silent witnesses to a lost tradition.

The Voynich Manuscript: Medieval Cipher or Elaborate Hoax?

The Voynich manuscript is an illustrated codex hand-written in an unknown script referred to as Voynichese, with vellum carbon-dated to the early 15th century between 1404 and 1438, and stylistic analysis has indicated the manuscript may have been composed in Italy during the Italian Renaissance. Now this one is different from the others because it’s a complete book filled with bizarre illustrations of unidentifiable plants, naked women in strange pools, and astronomical diagrams that don’t quite match any known system.

The Voynich manuscript has been studied by both professional and amateur cryptographers, including American and British codebreakers from both World War I and World War II, with codebreakers Prescott Currier, William Friedman, Elizebeth Friedman, and John Tiltman all unsuccessful. If the best codebreakers of the 20th century couldn’t crack it, what chance do the rest of us have? Yet people keep trying.

The text consists of over 170,000 characters divided into about 35,000 groups referred to as words, and the structure of these words seems to follow phonological or orthographic laws of some sort, with certain characters that must appear in each word, some characters that never follow others, and some that may be doubled or tripled but others may not. It looks like language, it feels like language, but is it? Recent research showing a cipher could generate text with striking similarities to the Voynich Manuscript does not necessarily mean it is a ciphertext, but it shows such a system could generate something very similar, though the study does not mean it’s case closed as this enigmatic book remains as elusive as ever.

The Phaistos Disc: A Unique Enigma

The Phaistos Disc was found in the Minoan Palace of Phaistos on Crete in 1908 and is thought to date from the 17th century BC, with an unknown script inscribed on it and many theories about the language it represents and what it means, yet no other evidence of this script has been found. Imagine discovering a single object with writing unlike anything else ever found. That’s the Phaistos Disc in a nutshell.

This clay disc, about six inches in diameter, contains 241 symbols stamped into both sides in a spiral pattern. The symbols were made using stamps, which is remarkable because it suggests a form of printing technology existed in the ancient Mediterranean. Yet we have only this one disc. No other examples, no practice pieces, no fragments.

The Phaistos disc has been deciphered many times, including one interpretation as a double hymn to Zeus and the Minotaur. Without additional examples to test theories against, any proposed decipherment remains purely speculative. It’s hard to say for sure, but the disc might be a one-off creation, perhaps a game, a religious object, or even an ancient form of tourist souvenir.

The Olmec Glyphs: Mesoamerica’s Earliest Mystery

The Olmec script associated with one of Mesoamerica’s earliest major civilizations remains largely undeciphered, presenting a significant challenge to scholars, with key artifacts such as the Cascajal Block providing limited evidence, and primary obstacles including the scarcity of artifacts, the absence of a bilingual artifact akin to the Rosetta Stone, and the script’s isolation from known languages. The Olmecs are often called the mother culture of Mesoamerica, influencing the Maya and Aztecs who came after them.

We know the Olmecs were sophisticated. They carved massive stone heads weighing several tons and transported them over considerable distances. They developed complex societies with long-distance trade networks. Yet when it comes to their writing system, we’re largely in the dark. The handful of inscriptions we have are too few to establish clear patterns or test decipherment theories properly.

What makes this particularly frustrating is that their cultural descendants like the Maya developed extensive written records that we can now read. Somewhere in that transmission from Olmec to Maya, crucial information about the earliest script was lost. You’re looking at the roots of an entire writing tradition, yet those roots remain obscure.

Etruscan: The Partially Understood Language

While not entirely undeciphered, the Etruscan language used in ancient Italy still poses significant challenges, with some vocabulary and structure understood thanks to bilingual inscriptions and borrowings in Latin, yet much of the language, especially its non-Latin vocabulary, remains enigmatic, and the Etruscans were a significant influence on Roman culture. This is where things get interesting in a different way. We can actually read Etruscan writing because they used an alphabet similar to Greek and Latin.

The problem isn’t the script itself but the language. It doesn’t belong to the Indo-European family like Latin, Greek, or English. That means even when you can sound out the words, you often have no idea what they mean because there are no related languages to compare them against. Imagine being able to pronounce every word in a book but understanding only occasional terms that happened to be borrowed into Latin.

The Etruscans dominated central Italy before Rome rose to power, and Roman civilization absorbed many Etruscan customs, religious practices, and technologies. A fuller understanding of their language would illuminate early Roman history and reveal more about a civilization that preferred to remain somewhat mysterious to outsiders.

Ancient Cretan Hieroglyphs: The Island’s First Script

Cretan hieroglyphs date to approximately 2100 BC, and along with Linear A are scripts from an unknown language, one possibility being a yet to be deciphered Minoan language, with several words having been decoded from the scripts but no definite conclusions on the meanings of the words. Before Linear A appeared on Crete, the Minoans used an even earlier writing system that consisted of pictographic symbols resembling Egyptian hieroglyphs, hence the name.

This script represents the very beginning of writing on Crete. The symbols include representations of body parts, tools, vessels, and other everyday objects. Like Linear A and the Phaistos Disc, Cretan hieroglyphs remain undeciphered because we lack sufficient text and context to work with. Most surviving examples are short inscriptions on seals used to mark property or authorize transactions.

The existence of three different writing systems on Bronze Age Crete speaks to a culture that valued written communication and administration. Yet ironically, their eagerness to write has left us with mysteries we can’t solve precisely because each system was eventually abandoned and the knowledge of how to read them disappeared.

The Role of Technology in Modern Decipherment Efforts

In the past few decades, innovative technology has been advancing not only our ability to decode these ancient scripts but also to recover information from objects once thought too damaged to be understood, with tools like X-rays, CT scans, and AI helping today’s scholars tease out the contents of seemingly impossible sources. We’re living in an exciting time for archaeological linguistics. Computers can now process statistical patterns across thousands of symbols faster than any human could manage.

In 2019 MIT researchers developed an algorithm informed by patterns in how languages change over time to align words from a lost language with their counterparts in a known language, effectively translating what may be possible to understand, with the technology tested on Linear B and producing results with remarkable accuracy. Machine learning algorithms can identify patterns invisible to the human eye and test thousands of hypotheses in the time it would take a scholar to test just a few.

However, there’s a catch. While technology highlights a future for the decipherment of scripts, it’s essential to realize that human research is still imperative to decoding the enigma. Computers can suggest patterns and possibilities, but human expertise is needed to evaluate whether those suggestions make linguistic, cultural, and historical sense. The best approach combines computational power with scholarly wisdom.

Why Do These Scripts Matter?

You might wonder why we should care about these ancient puzzles. After all, the civilizations that created them are long gone. The thing is, these scripts are time capsules containing voices that went silent millennia ago. Each undeciphered writing system represents entire populations whose thoughts, beliefs, administrative records, poetry, and knowledge remain locked away from us.

Deciphering these scripts could revolutionize our understanding of human history. The Indus Valley civilization might reveal unexpected connections between ancient India and Mesopotamia. Rongorongo could tell us how Polynesian cultures developed their own writing independently. Proto-Elamite might show us economic systems we never knew existed. The Voynich manuscript might contain medical knowledge or astronomical observations we’ve overlooked.

Beyond the specific information they contain, these mysteries remind us of the fragility of knowledge transmission. Entire writing systems can disappear in a single generation if the people who understand them vanish through disease, war, or cultural upheaval. They’re cautionary tales about preservation and the importance of maintaining connections between generations. When you look at these undeciphered scripts, you’re seeing what happens when that chain of knowledge gets broken. What do you think about it? Did you expect that so many ancient writing systems would still remain mysterious after centuries of study?

Jan loves Wildlife and Animals and is one of the founders of Animals Around The Globe. He holds an MSc in Finance & Economics and is a passionate PADI Open Water Diver. His favorite animals are Mountain Gorillas, Tigers, and Great White Sharks. He lived in South Africa, Germany, the USA, Ireland, Italy, China, and Australia. Before AATG, Jan worked for Google, Axel Springer, BMW and others.