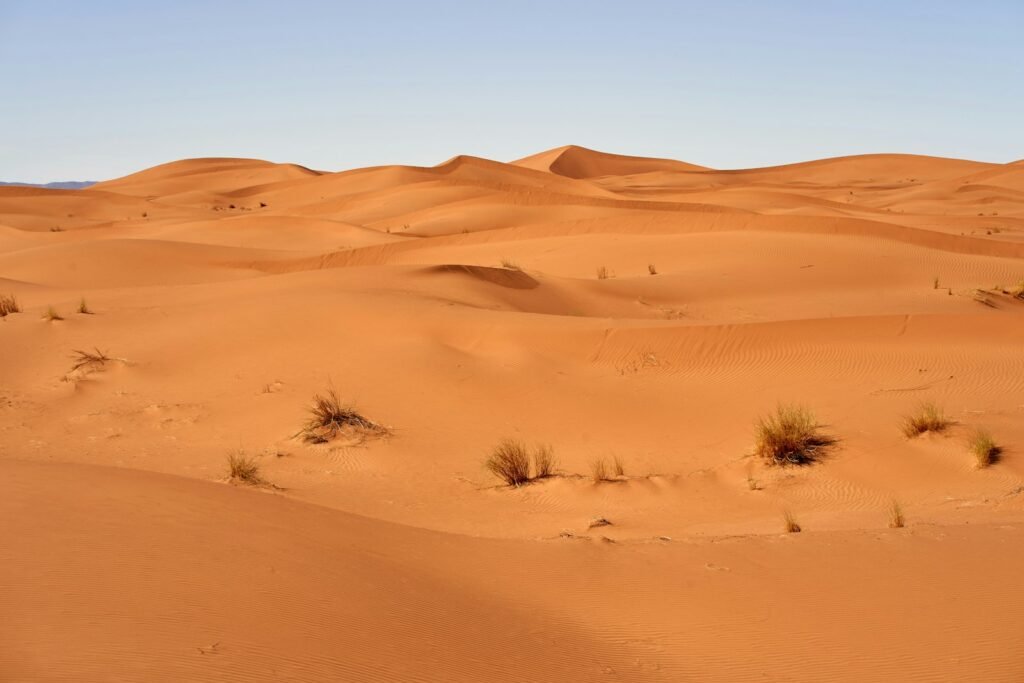

Today the Sahara stretches across North Africa like a vast, sun-baked ocean of sand, but the latest science tells a very different story about its past. Beneath those dunes lie the fingerprints of rivers, lakes, and thriving ecosystems that once supported hippos, crocodiles, and human communities. For decades, scattered fossils and rock art hinted at a greener Sahara, but only recently have satellites, sediment cores, and climate models pieced together the scale of this transformation. The mystery now is not just how such a radical change happened, but what it can teach us about Earth’s climate future. As researchers reassemble this lost world, the Sahara becomes less a barren wasteland and more a time capsule of rapid environmental change.

The Hidden Clues Beneath the Sand

The idea of a green Sahara sounds almost like fantasy until you start looking closely at the evidence buried and etched across the region. In remote outcrops, you find rock art showing giraffes, cattle, and swimming humans where there is now only dust and stone. Ancient shorelines traced along now-dry basins reveal the outlines of immense lakes, some larger than many modern countries. Fossilized bones of hippos and crocodiles have been uncovered deep in the desert, species that simply could not survive there today. Each of these clues, taken alone, is intriguing; taken together, they sketch a startlingly different landscape.

What has really transformed the picture in the last couple of decades is the view from above and below. Satellite radar has mapped buried river systems, sometimes called “paleorivers,” snaking invisibly beneath sand seas. Sediment cores drilled from ancient lakebeds show layers rich in pollen from grasses and trees, alongside freshwater shells and organic matter that only form in wetter conditions. Even dust blown from the Sahara and trapped in ocean sediments carries a chemical and mineral record of when the region was vegetated versus bare. It is as if the desert has been keeping a multi-layered diary, and scientists are finally learning how to read it.

A Green Sahara: Lakes, Rivers, and Teeming Wildlife

During its green phases, the Sahara was not just a little wetter; it was a radically different world. Climate reconstructions suggest that from roughly about eleven thousand to five thousand years ago, much of what is now hyper-arid desert hosted seasonal grasslands, scattered woodlands, and a network of lakes and wetlands. One of the most striking examples is the so-called “Mega-Lake Chad,” which at its largest may have covered an area several times greater than the present-day Lake Chad. Imagine standing in what is now a dune field and instead seeing open water stretching to the horizon, framed by reeds and grazing animals.

Wildlife followed the water and vegetation. Fossil and archaeological finds show that large mammals typical of savannah environments – antelope, elephants, and even hippos – roamed across regions that are now among the driest on Earth. Crocodiles occupied river channels and lakes, and fish remains indicate that freshwater ecosystems were surprisingly rich. For humans, this landscape was a hospitable corridor, not a barrier, with evidence of fishing, herding, and early farming communities. That alone changes how we think about the Sahara: less an eternal dividing line between North and sub-Saharan Africa, and more a dynamic bridge that opened and closed over time.

From Ancient Tools to Modern Science

The earliest hints of a green Sahara came from archaeologists and explorers stumbling across stone tools, pottery shards, and rock engravings far from any permanent water source. These finds raised nagging questions: who lived here, and under what conditions, when today survival would be nearly impossible without modern technology? For a long time, the answer leaned heavily on interpretation and guesswork, grounded in local evidence but lacking a broader, dated framework. The story felt more like a patchwork of anecdotes than a coherent chapter of Earth history. That started to shift when scientists began integrating archaeology with geochemistry, remote sensing, and climate modeling.

Now, researchers can date lake sediments using isotopes, analyze fossil pollen to reconstruct vegetation, and compare those records with simulations of how Earth’s orbit altered incoming sunlight. Orbital changes, particularly in the tilt and wobble of the planet, intensified the African monsoon at certain intervals, delivering abundant rainfall deep into the Sahara. This idea moved the green Sahara from speculation to a repeatable, testable phenomenon that appears many times across the last few hundred thousand years. The story is no longer just about scattered tools and paintings; it sits squarely in the intersection of human history, planetary motion, and atmospheric physics. To me, that blend of the very human and the cosmic is what makes this field so addictive.

Climate Rhythms: Why the Sahara Turned Green – and Brown Again

The transformation of the Sahara from lush to barren is not a one-off catastrophe but part of a natural rhythm driven by subtle shifts in Earth’s orbit. When the Northern Hemisphere leans closer to the Sun during its summer, the land heats more strongly and the West African monsoon is energized, pushing rainfall hundreds of miles farther north. Over thousands of years, this enhanced monsoon pulses in and out, creating what scientists call “African Humid Periods” – windows of several thousand years when the desert blossoms. In these intervals, plants establish themselves, soils form, and lakes expand, reinforcing the wetter climate through local feedbacks.

But the same orbital machinery that switches on the rain eventually dials it back down. As incoming summer sunlight decreases, the monsoon weakens, vegetation thins, and bare ground reflects more sunlight, further drying the region. One of the big debates in current research is how abrupt the last big transition was – from green to desert roughly about five to six thousand years ago. Some records suggest a gradual decline; others point to relatively rapid tipping points in certain areas. Either way, what stands out is that a huge region of Earth reorganized itself in a geologically short time, shifting from a habitable mosaic to the vast arid expanse we recognize on today’s maps.

Why It Matters: Lessons from a Vanished Landscape

The green Sahara is not just a cool piece of trivia to impress friends at dinner; it is a real-world experiment in rapid climate and ecosystem change. When I first read papers on this topic, what struck me most was how quickly human societies had to adapt to shifting water and resources. As lakes shrank and rainfall retreated, people moved, technologies changed, and cultural networks reoriented, leaving archaeological fingerprints from the Nile valley to the Sahel. Those ancient migrations are now thought to have influenced the spread of pastoralism and agriculture across Africa and even into the Mediterranean fringes. In other words, the Sahara’s mood swings helped steer human history.

From a climate science perspective, the green Sahara is a stress test for our models. If we cannot accurately reproduce a past shift as large as this, our confidence in predicting future regional changes is on shakier ground. It also forces us to confront the idea of thresholds: how much pressure can a landscape take before it flips into a new state that is hard to reverse? Compared to today’s human-driven greenhouse gas emissions, the Sahara’s past changes were triggered by natural orbital cycles, but the scale of ecological reorganization feels eerily familiar. The takeaway is unsettling but powerful: Earth’s systems can and do reconfigure dramatically, and living beings – humans included – either adjust, move, or lose out.

People of the Green Sahara: Lives Along Vanished Shores

It is easy to picture the green Sahara as a lonely wilderness of animals and plants, but people were very much part of that ecosystem. Archaeological surveys have revealed settlements clustered around ancient lake margins, sometimes with evidence of fish processing, animal herding, and even early attempts at cultivating plants. Pottery fragments decorated with aquatic motifs, grinding stones, and hearth remains hint at daily routines centered on water-rich environments. Rock art scenes show cattle in orderly lines, hunters with bows, and human figures that seem almost celebratory in their watery world. These were not marginal survivors; they were communities thriving in what was, at the time, prime real estate.

As the climate dried, those communities faced choices that feel surprisingly contemporary: stay and adapt, or leave and seek more reliable conditions. Many appear to have tracked the retreating rains and waterways toward the Nile, the Sahel, and other refuges. This movement likely fed into the rise of more complex societies along the Nile, where the river provided a relatively stable lifeline even as the broader region desiccated. The story complicates simple narratives of “cradles of civilization” by showing how environmental stress and opportunity can push people into new configurations. In that sense, the lost lakes of the Sahara echo in the crowded river valleys and coastal cities of our own time.

Global Perspectives: A Desert That Talks to the World

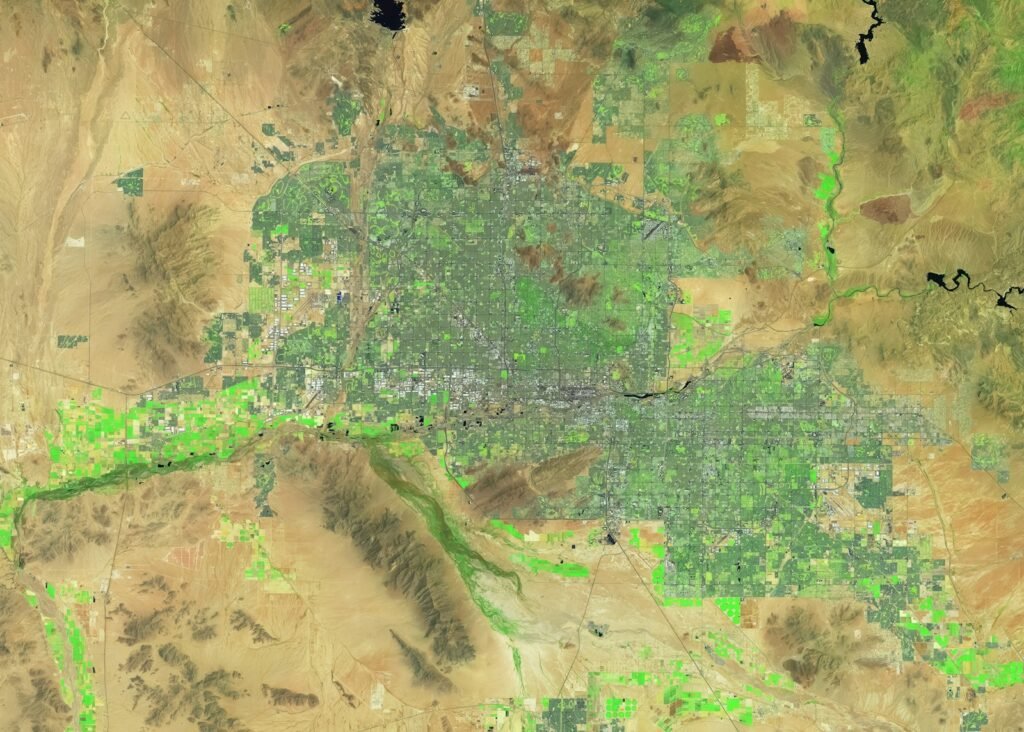

Even in its dusty modern state, the Sahara remains deeply connected to the rest of the planet, and its green past helps explain why those links are so strong. Today, enormous plumes of Saharan dust cross the Atlantic, fertilizing the Amazon rainforest with minerals and shaping atmospheric conditions thousands of miles away. That same dust can worsen air quality in Europe and influence hurricane formation in the tropical Atlantic. When the Sahara was vegetated, the amount and composition of dust it exported were very different, altering everything from ocean productivity to distant climate patterns. So the green Sahara was not just a local phenomenon; it was a player in the planetary system.

Looking beyond Africa, the Sahara’s story ties into other regions that have swung between wetter and drier states, like the Arabian Peninsula and parts of Asia. Together, these cases highlight how monsoon systems and high-latitude ice sheets interact in complex, sometimes surprising ways. By comparing records from different continents, scientists can tease out which changes are global signals and which are local quirks. This broader view is crucial because our current climate crisis is undeniably global, even though its impacts are patchy and region-specific. The vanished wetlands and forests of the Sahara thus become part of a much larger atlas of Earth’s shifting climate zones.

The Future Landscape: Will the Sahara Turn Green Again?

One of the most tantalizing questions is whether the Sahara could become green again, and if so, on what timeline and under what conditions. Purely from an orbital standpoint, another African Humid Period would be expected in the distant future as Earth’s tilt and wobble continue their cycles. However, human-driven climate change has now added a powerful new factor that could disrupt or reshape these natural rhythms. Some modeling studies suggest that certain greenhouse gas pathways might intensify rainfall over the Sahel and parts of the Sahara, while others point to more complicated, regionally uneven outcomes. The desert’s future, in other words, will not simply replay its past in a neat loop.

There are also bold geoengineering and reforestation concepts that imagine deliberately greening parts of the Sahara to draw down carbon dioxide or generate solar-powered electricity at massive scale. While these ideas sound visionary, they raise hard questions about unintended consequences for regional weather, ocean circulation, and neighboring societies. Changing land cover on such a huge area could alter monsoon dynamics and dust transport in ways we do not fully understand. The green Sahara reminds us that even natural vegetation shifts can restructure climate; doing something similar by design is a gamble we should approach with extreme caution. The landscape’s past flexibility is inspiring, but it is also a warning label.

How You Can Engage With a Lost Green World

You might never stand on the floor of a vanished Saharan lake, but there are surprisingly concrete ways to connect with this hidden chapter of Earth’s story. One simple step is to seek out high-quality visualizations and reconstructions from research institutions and science museums; seeing maps of ancient rivers and lakes can make the green Sahara feel real rather than abstract. Supporting organizations that preserve rock art and archaeological sites across the Sahara and Sahel helps protect fragile evidence that is still eroding under modern pressures. Paying attention to reporting on climate, migration, and water stress in North Africa and the Sahel can also reframe current events as the latest phase in a very long environmental saga. Even choosing to read and share science journalism on topics like this keeps the conversation alive beyond academic circles.

If you are inclined to go a bit deeper, you can follow open-access paleoclimate projects or citizen science efforts that map ancient landscapes and human routes. Conversations about climate policy often feel stuck in the present or near future, but using the green Sahara as a reference point can anchor those debates in Earth’s actual track record of change. This history shows that landscapes and societies are linked in ways that are both resilient and vulnerable. The desert we see today is only one version of what this region can be – so the real question is what role we choose to play in shaping the next chapter.

Suhail Ahmed is a passionate digital professional and nature enthusiast with over 8 years of experience in content strategy, SEO, web development, and digital operations. Alongside his freelance journey, Suhail actively contributes to nature and wildlife platforms like Discover Wildlife, where he channels his curiosity for the planet into engaging, educational storytelling.

With a strong background in managing digital ecosystems — from ecommerce stores and WordPress websites to social media and automation — Suhail merges technical precision with creative insight. His content reflects a rare balance: SEO-friendly yet deeply human, data-informed yet emotionally resonant.

Driven by a love for discovery and storytelling, Suhail believes in using digital platforms to amplify causes that matter — especially those protecting Earth’s biodiversity and inspiring sustainable living. Whether he’s managing online projects or crafting wildlife content, his goal remains the same: to inform, inspire, and leave a positive digital footprint.